今野真二

高知にうまれた植物学者、牧野富太郎(1862-1957)は、具体的に1つの立体として存在している植物の「総体」を1つの平面上にあらわした植物画を描いている。花が咲き終わってから実がなるという「具体」をもとにして、1つの平面に、花と実、さらには種子までも描くことはきわめて高度な「抽象」といえるだろう。牧野富太郎の植物画においては、立体が2次元の平面に移されている。

牧野富太郎が『大日本植物誌』第1巻第2集の第7図版として描いたサクユリの図を表紙にした、今野真二『消された漱石』(2008年、笠間書院)は「本文」をまんなかにして、下段に「註」、上段に「コラム」を配した3段組の体裁を採る。これはいわば言語の「線条性」にいくぶんなりとも抗おうとしたレイアウトであったが、読者に「読みにくい」と言われることもあった。一般的な書物の形態によって提示できる「情報」には「制約・制限」があるということを「書き手」も「読み手」も認識しておく必要があるだろう。

言語にはさまざまな特徴があるが、「線条性(linearity)」は「言語記号の恣意性」とともに重要な特徴といってよい。「線条性」は言語が〈線のような性質〉をもっているということであるが、〈線のような性質〉は「初めがあって終わりがある」(性質)と言い換えることができる。「はなしことば」には話し始めがあり、話し終わりがある。「かきことば」としてアウトプットされている言語は、テキストを単位とするならば、後ろのほうを先に読み、前のほうを後に読むこともできる。しかし、「文」や「語」を後ろから読むことはできない。いかに斬新な工夫を採り入れている小説作品であっても、基本的には「線条性」に従って、語を並べていくしかない。

詩が基本的に句読点を使わないこと、頻繁に改行されたかたちで文字化されていることは、詩的言語がひと続きの「文」としてアウトプットされているのではないことを示しているとみることができる(注1)。ここに注を附して、言説を分けたこと、そのこと自体が、「線条性」では述べにくいことを述べるための「工夫」といってよい。

詩的言語は、言語の「線条性」からなにほどかにしても離れることによって、言語でありながら通常の言語との「違い」を獲得していると思われる。そのような詩であっても、そうしたことを積極的に表現としていない作品においては、やはり「文」や「語」を後ろから読むことはできないし、作品も、基本的には始めから終わりに向かって読んでいくことになる。言語における「線条性」は重要な特徴であるとともに、強い「制限」でもある。

そうした強い「制限」からかなりな程度「解放」されているのがコミック(漫画・マンガ)であろう。

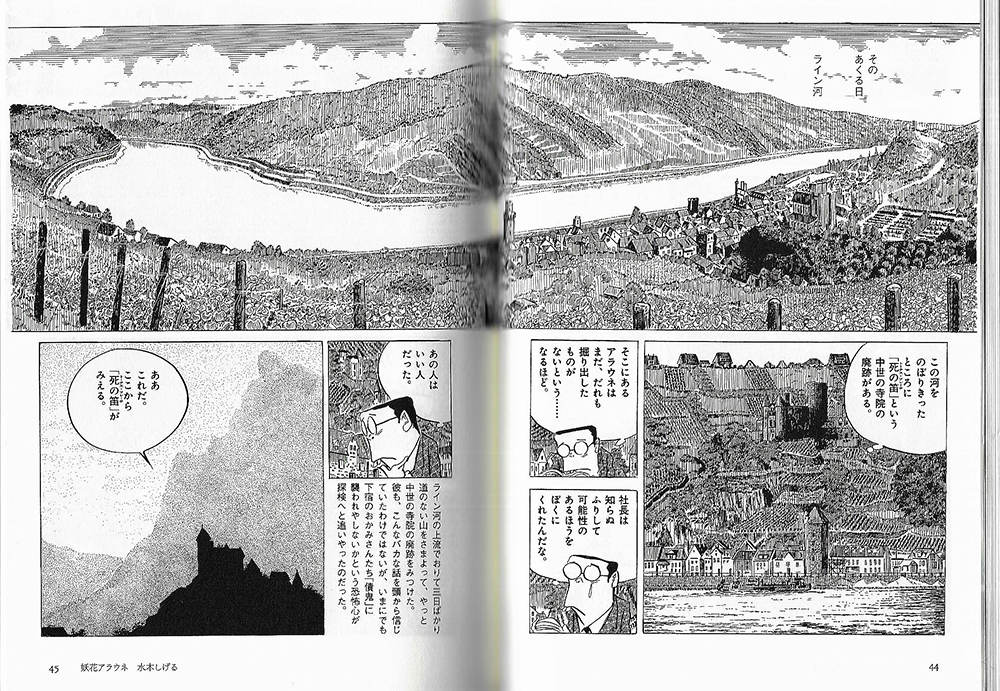

図1は「ドイツの小都市」で登場人物の「山本」が「黄色い花をもった植物の根からできる妖怪」「アラウネ」に巡り会うという、水木しげるの「妖花アラウネ」の見開き2頁(44-45頁)である。『日本短編漫画傑作集2』では37頁がタイトル頁となっていて、38頁から作品が始まり、68頁で作品が終わる。「フキダシ」の中のことばは右縦書きに印刷され、作品全体も右縦書きを基本として頁が進んでいく。

この見開き2頁においては、上部に頁をまたがったかたちで、コマが設定され、雄大なライン河が描かれている。その他のコマは右から左へと右縦書きの「ルール」に従って展開している。いささか大げさな物言いになるかもしれないが、この見開きは言語の「線条性」にとらわれていないといえるだろう。「その/あくる日/ライン河」(/は改行位置を示す)という文字は44頁側にのみあるが、「読み手」の視線は当然文字のない45頁側にも向けられる。

2頁にまたがったコマの下に、44頁には3つのコマ、45頁には2つのコマが設けられ、45頁ではコマが設定されていないところに「ライン河の上流でおりて三日ばかり/道のない山をさまよって、やっと/中世の寺院の廃跡をみつけた。/彼も、こんなバカな話を頭から信じていたわけではないが、いまにでも下宿のおかみさんたち「債鬼」に/襲われやしないかという恐怖心が探検へと追いやったのだった。」という、説明的な「地の文」が置かれている。この「地の文」で使われている文字の大きさ、フォントは「フキダシ」の中で使われている文字の大きさ、フォントと異なっている。さらにいえば、2頁にまたがったコマの中にある「その/あくる日/ライン河」の文字の大きさ、フォントとも異なっている。「地の文」は作者=書き手のことばであると粗くとらえておくことにするが、そうであれば、フォントによっておおげさにいえば、「言語主体」を区別していることになる。そしてまた、そうすることによって、多くの「言語主体」を比較的わかりやすい、かつ単純なやりかたで区別することができる。

小説などの文学作品において、印刷に使われている文字の大きさ、フォントは一定であることが一般的といってよいだろう。もちろん文字の大きさを変えずに、ある語をゴシック体にするということはあり得るが、明朝体に隷書体を混ぜ用いるといったことは通常は考えにくい。そうしたことが技術的にはさほど難しくないと思われるにもかかわらず、行なわれていない理由としてはさまざまなことが推測できるが、言語を表現の軸としている文学作品においては、言語の可読性、読みやすさを保証することが重要であるために、文字の大きさを変えることやフォントを複数使用することを避けているのではないかと思われる。そう考えると、「言語・文字+絵」を表現の手段としているコミック(漫画・マンガ)においては、文学作品のようには、文字の可読性に留意しなくてもよいことになる。そこにコミックの表現の幅がうまれる。

「地の文」をよくみると、「みつけた。」の後にはまだ余白があり、「彼も」をそこに印刷することもできた。しかしそうせずに「彼も」は次の行に印刷をした。通常の文章であれば、これは段落ということになり、段落の始まりは1字あけることになるが、1字あけはなされていない。現在、インターネット上に公開されている文章などでは、段落の始まりを1字あけないことがある。段落の始まりを1字あけるのは、そこが段落の始まりであることを視覚的に示すためと思われるが、インターネット上ではレイアウトが自由にでき、原稿用紙に書くような形で、文字を並べなくてもよい場合がある。あるいは原稿用紙に書くような形で、文字を並べることができないことがある。インターネット上のことばは、きわめて自然に通常の言語が受けている「制限」を離れ、きわめて自然に通常の言語の「ルール」を離れつつあるようにみえる。

44頁の3つのコマと45頁の「あの人は/いい人/だった。」という「フキダシ」の最後の部分には丸くなっている。それに対して45頁の「ああ/これだ。ここから/「死の笛(右振仮名:トーテス・フレーテ)が/みえる。」という「フキダシ」は最後の部分がとがっている。この作品の他の箇所をみると、最後の部分がとがっている「フキダシ」は現実の(といういいかたはコミックに関しておかしいが)会話の場合、最後の部分が丸い「フキダシ」は「心の中のことば」のような場合、と区別されていることが推測できる。

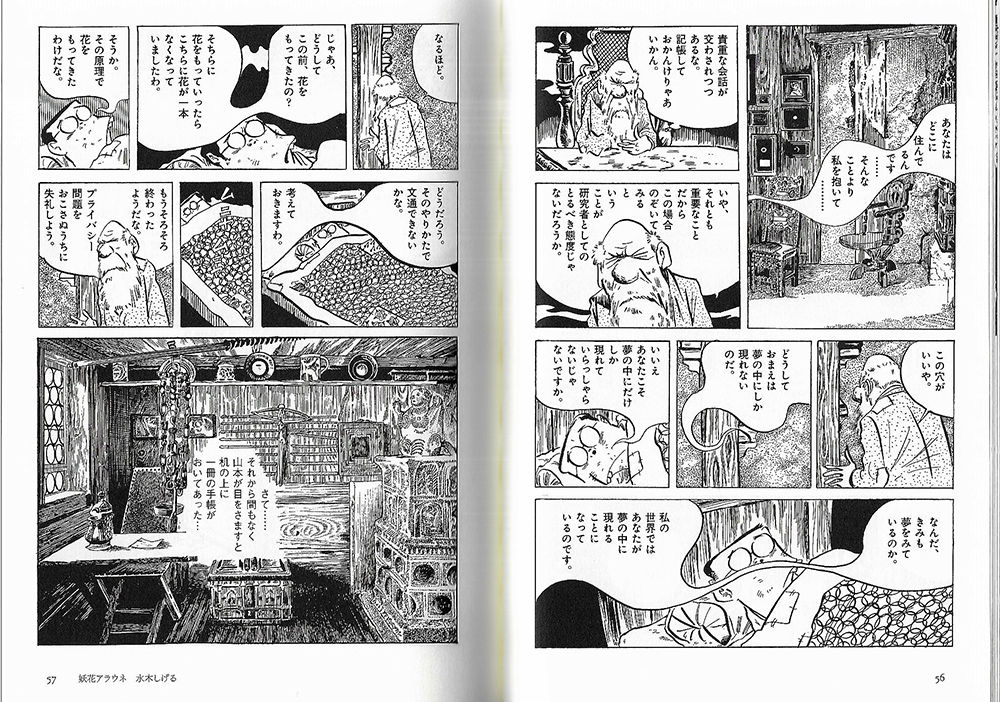

図2は同じ作品の56-57頁であるが、例えば56頁の下のコマの「フキダシ」「なんだ、/きみも/夢をみて/いるのか。」「私の/世界では/あなたが/夢の中に/現れる/ことに/なって/いるのです。」はことばが右と左とに分かれており、右は「山本」のことば、左は「アラウネ」のことばになっている。そしてこの「フキダシ」には「話し手」との接合部=先に、丸くなっているとかとがっているといった部分がない。57頁の「じゃあ、/どうして/この前、花を/もってきたの?」「そちらに/花をもっていったら/こちらに花が一本/なくなって/いましたわ。」も同様で、「山本」と「アラウネ」がいわば、異界の交信をしているような体になっている。こうしたこともコミックにおいてはごく自然に行なうことができる。

57頁には「ムニャムニャ」というオノマトペが「手書き文字」として示されている。他の箇所では、「ゴロロロロ」という「無気味な地鳴り」(46頁)、「カアー/カアー/カアー」(同前)というカラスの鳴き声、「キヤーッ」(47頁)という声、「ずるずる」(同前)という穴に落ちる音、「トントン」(49頁)という扉をたたく音などが「手書き文字」で示されている。

水木しげる「妖花アラウネ」は1968年、今から55年前に発表されている。その頃は「手書き文字」はいわばまだ控えめに使われていたといってよいだろう。現在のコミックにおいては、「手書き文字」はコミック作者の気持ちをあらわしたり、登場人物の「心の中のことば」をあらわしたり、とさまざまに使われている。

コミック作品をひろい意味合いで文学テキストに含めることはできるだろう。含めるのであれば、本稿はおもにコミック作品を採りあげて、その文字表現について述べたことになる。また、コミック作品を文学テキストに含めないのであれば、コミック作品がいわばやすやすと実現させている文字表現について述べることによって、案外と文学作品が言語がもつ「制約」下にあることを「反照的」に述べたことになる。

筆者は、コミックは「言語・文字+絵」を表現手段にしているという点において、挿絵をほとんど含まない文学作品とはメディアが異なると考える。したがって、まずはコミックと文学作品とは分けてとらえたい。しかしまた、挿絵がある程度含まれている、たとえば明治期の文学作品であれば、それにふさわしい観察、分析を行なう必要があると考える。

「言語・文字+絵」を表現手段としているコミックを丁寧に観察し分析することによって「言語・文字」が担うことができる情報がどういうもので、「絵」が担う情報がどういうものかということがつかめていくと思われる。そこでわかったことを文学作品に「反照」することで文学作品が文字表現として何が可能か、またどういうことをやってきて、どういうことをやってこなかったか、ということも明らかになると思われる。

注

注1 『現代詩手帖』第66巻第6号(2023年、思潮社)は「詩と小説 二刀流の現在」を特集しているが、小池昌代は「くるくると回っているものたち」において、浅田彰が坂本龍一についての「個人的な思い出を聞かれ、京都大徳寺真珠庵の茶室に皆で集った際」の驟雨の「雨音について語っていた」ことを紹介し、「詩とは、あの驟雨のように、いきなり切り込んできて前後の時空間を切断するものだ。そして驟雨について語った浅田氏の語り口も、驟雨の態様そのままに、その場に突如、差し込まれたように感じた。切断、と書いたが、切れていないものは詩ではないと思うくらいで、あるときからわたしは、「改行」というものを、詩の大事な要素として考えるようになった。切断されたことの証として、「短い」ということも詩の本質ではないかと思うようになった。短いということは物理的な意味では行が少ないということで、時間的な意味では一瞬ということである。人の世では、つながるということのほうについ積極的な意味が置かれるが、切断は人間が生きていくときに必要な概念で、そして「美」というものの存在様式には、接続より切断という要素が、より重要な働きをするのではないだろうか。切断があると、その「あいだ」を飛ぶことになるが、飛躍は結果として切れたもの同士をつなぐので、詩の足跡は、こうして切れながら続いていく点線のようなものになる。小説の言葉は点線では心もとない。どうしても太い実線を押し通していきたいし、いくことになる。だが詩を一つの概念として考えたとき、小説のなかにも詩があることに気づく。全体の形式は散文でも、細かくみると飛躍があり、言葉の前後に「切断」と「突出」がある」と述べている。

小池昌代の詩集『野Noemi笑』(2017年、澪標)に収められている「舗道」という作品には次のようなくだりがある。

ほの暗い店で 食事をとった

一皿料理のたくさん並ぶ店

鼻歌も つかの間 途切れ

なぜ わたしを 捨てたの

壁から湧く声は

ノエミのものか

別の女か

わたしの声か

詩集は右縦書き(右から左に行がすすむ縦書き)で印刷されており、ここではそれを左横書きに変えているが、縦書きにアウトプットされている詩を横書きにすることによって、詩作品に変更が加えられているとみることは当然できる。そしてそういうことをまったく気にしない読み手がいる一方で、気になる読み手もいることが予想される。右縦書きで印刷されている新聞において、「10」の下に「年」と表示されていて、それを右縦書きで「一〇年」あるいは「十年」と表示した時、左横書きで「10年」と表示した時、「何か」が変わったとみるのか、変わらないとみるのか、そういうことについての日本語母語話者の「共通認識」が形成されているわけではない。「文学(literature)」はさまざまに定義できるであろうが、どのように定義したとしても「言語による芸術」であることは定義に含まれるだろう。そうであるならば、詩に限らず、およそ文学作品とみなし得る作品においては、表現の根幹にある言語について、すみずみまで気を配った「よみ」が求められることはむしろ自然といってよい。しかしまた文学作品を「あらすじ」で理解するということも行なわれている。ヒトという生物のいとなみ、認知が「具体」と「抽象」をいききしているといえようが、「文学」という枠組みの中で生成されアウトプットされているテキストはやはり「あらすじ」ではなく、言語によってどのように表現がかたちづくられているか、に目配りをする必要があるだろう。

今野真二(2017)において恩地孝四郎(1934)を採りあげ、絵画作品をみる人は「絵画作品に描かれている「実存物」(恩地孝四郎1992:344頁)に引きずられやすい。リンゴが描かれているとリンゴの絵だと言語化して、分かったと思い込む。こうなると「云い現わし得ないもの」(同前)が描かれている絵画作品は「模糊曖昧物として外道に置かれる。怪奇とされる」(同前)ということになる」(18頁)と述べた。リンゴが描かれている絵画を「リンゴの絵」ととらえることは、絵画作品における「あらすじ」といってよいだろう。

梅原龍三郎(1888-1986)は1950年に「浅間山」と題されている作品(メナード美術館蔵)を描き、続く1951年にもやはり「浅間山」と題されている作品(個人蔵)を描き、1952年頃に「浅間」と題されている作品(個人蔵)を描き、1953年には「噴煙」と題されている作品(東京国立近代美術館蔵)を描いている。これらはすべて浅間山を描いたものであるが、「梅原龍三郎が浅間山を描いた作品」とくくるならば、これらはみな同じ作品ということになってしまう。描かれている「実存物」は浅間山であっても、それぞれの作品は具体相において異なる。その具体相を話題にせずに絵画作品について述べることはできないだろう。

ポーラ美術館にはクロード・モネ(Claude Monet)が1899年に描いた「Water Lily Pond」(睡蓮の池)と1907年に描いた「Water Lilies」(睡蓮)とが蔵され、国立西洋美術館(松方コレクション)には1916年に描いた「Water Lilies」(睡蓮)が蔵されている。これらはいずれも睡蓮を描いた作品であるが、「どれも睡蓮を描いた作品」とくくることはできないだろう。いかに描いているか、いかに表現しているか、を注視する必要がある。

言語表現が文字によって視覚化されていることからすれば、詩的言語としてアウトプットされている作品・テキストについては、文字についても目配りをする必要があることになる。上の引用は、右縦書きされているものを左横書きにしたが、いわゆる「レイアウト」は左横書きの中で、できるだけ再現した。例えば右縦書きにおいても、3行目の「鼻歌も」は1-2行目よりも1字下がった位置に印刷されており、「鼻歌も」の後には1字分の空白がある。詩集のタイトル『野Noemi笑』はどのように発音すればよいのだろうか。何も考えなければ、「野」と「笑」との間の「Noemi」は「野笑」の発音を示すために補助的に加えられているとみて、詩集のタイトルは「ノエミ」だと思うだろう。「それでいい」ともいえるし、「そういうことではない」ともいえるだろう。「そういうことではない」は、この詩集はタイトルから、言語の線条性に抗っているのだ、というみかたで、小池昌代の意図は小池昌代に尋ねるしかないが、少なくとも「線条性への抵抗」を可能性として含むと推測する。この「舗道」という作品には次のようなくだりもある。

だから

うなだれないで

空を見て歩こう

「空を見て歩こう」は「だから」よりも1字下がった位置から始まる。「だから」と「うなだれないで」の間は1行あいているようにみえる。「うなだれないで」は「歩こう」の「こ」よりも少し上の位置から始まる。「だから」の次がなぜ空白行になっているのか、「うなだれないで」はなぜその位置に印刷されているのか、それを考え、想像することが「文学」のすべてではないにしても、それが「文学」といってよいはずだ。

参考文献

恩地孝四郎 1934 「写実・象徴・抽象・表出」(後、1992年、阿部出版『抽象の表情』)

今野真二 2017 『詩的言語と絵画』(勉誠出版)

The Architecture of Written Japanese

13 The Visual Representation of Language in Literary Texts

Chris Lowy

In this, the penultimate installment in our series on the Japanese writing system, I discuss how the architectural features of the script enable the creation of unique text-worlds, and how an understanding of what a text-world is can expand our understanding of literature in general. For this reason, much of my discussion here is not as Japan-focused as in previous installments. Additionally, I bring what I’ve been calling a script architecture into dialogue with the emerging field of grapholinguistics. These points reinforce a key contention of this serialization: if the practice of literature is rooted in language, then a deeper understanding of how language is represented in literature should tell us something about the nature of language, too.

Towards a Definition of Text-World

What do you see when you open a book? Pictures, maybe, but certainly words. Then you begin reading a novel or poem. Perhaps those words usher you into a world different from the one around you. At the same time, maybe unbeknownst to you, you are also now navigating a text-world. This text-world, just like the content it contains, is of an author’s making. It is the author’s because they’ve created it, and just as every author is different, so too are the text-worlds they create. Similarly, every discrete text possesses a discrete text-world. Such text-worlds have the potential to create meaning on a dimension separate from, but nevertheless tied to, the language it represents. The text-world as a discursive space has been neglected as such because it sits at the intersection of language and content. It is neglected because it functions as an intermediate step in the process of creating of a larger fictional world.

We can push this conversation one step further: when an author begins writing a piece of literary fiction they are, at the same time – and whether they themselves know it or not – engaging in the process of worldbuilding. My use of the term differs in significant ways from how it is typically used. Trent Hergenrader, for example, in Collaborative Worldbuilding for Writers and Gamers, understands worldbuilding as

the process of creating a representation of a fictional world. It encompasses more than just the setting where a story takes place. It includes the political and social forces at work, logistical questions pertaining to geography and economics, and much, much more.[1]

Hergenrader also includes Chuck Wendig’s explanation of the term.

It’s easy to think [worldbuilding] means “setting,” but that’s way too simple—worldbuilding covers everything and anything inside that world. Money, clothing, territorial boundaries, tribal customs, building materials, imports and exports, transportation, sex, food, the various types of monkeys people possess, whether the world does or does not contain Satanic “twerking” rites.[2]

All of this is true, of course, but its focus on the “inside” of the world omits something important: by what means and in what way is this information delivered to the reader? Put another way, if worldbuilding is the product of an author’s construction, then it is language and its visual representation that serves as the building blocks of that world. Such an omission is to be expected because in some – perhaps most – texts, the visual representation of language is normative: it conforms to conventional orthographical and spelling standards and, as such, fades into the background. In such a situation, the visual representation of language is regarded as so inoffensive, so unremarkable, that it brings about a type of sublimation: the building blocks (i.e., the visual representation of language) of the fictional world disappear and the focus of the reader-critic falls onto (an abstracted notion of) narrative content. This is usually the default for literature written in alphabetic scripts.[3] This situation reaffirms the so-called “written language bias” in linguistics, a bias I touched upon in the previous installment and return to later in this one.

But the world is not built out of ABCs alone. The literary experience, if such a thing can be regarded as universal, emerges from all manner of written language. We do ourselves a disservice by extrapolating from a single context. In Japanese-language literature the written (or typed or printed) language by which information is transferred from author to text to reader is an important part of the worldbuilding process. In fact, not only is it a process but, at the same time, becomes a part of the world it is creating. The result of this process is what I have been calling a text-world. Because each text-world is unique, the function of a given text-world must be determined from an analysis of the negotiations between narrative content and the visual representation of language. There are a few caveats to consider before moving on. First, a text-world need not be the result of a single author, nor must it be intentional. Throughout Japan’s literary history, for example, editors have often inserted their hands into manuscripts at various stages along the road to publication (or dissemination), adding reading or punctuation marks as they see fit, and exercising the principle of interchangeability to visually represent the same “word” (kotoba) in another way. This is not limited to the premodern period (recall my discussion of Natsume Soseki’s Kokoro in Interchangeability) nor to Japan: the formidable task of discerning what an author “means,” what their “intent” is, was the primary goal of the mid-20th century scholarly movement known as New Criticism. One way this was (imagined to be) achieved was by deducing authorial intent through a comparative study of various extant manuscripts, the result of which would be a Frankenstein-like Ur text. This authoritative version – often a text stitched together from numerous manuscripts or prints – would then serve as the foundation for research and study. For a summary of the issue as it relates to English literature see Jerome McGann’s important A Critique of Modern Textual Criticism (University Press of Virginia, 1992) and, especially relevant to the above discussion, chapter five, “Final Intentions and Textual Versions” (55-63).[4] Through this process of creating an authoritative text a new text-world is born. The difference is that this new text-world resulting from the editorial process, the “stitching” referenced above, is nothing more than the by-product of the drive to create an authoritative text. That in and of itself is not an issue; what we’ve been thinking about the past year, though, are text-worlds of intention, ones whose relationship to narrative content ought not be overlooked for the role they play in literary fiction. This question of a text-world – a decidedly “literary” term – seems in part related to the emerging field of grapholinguistics, a decidedly “linguisticy” term.

Grapholinguistics

I suspect many readers are encountering the term “grapholinguistics” for the first time. Martin Neef defines it succinctly, if not vaguely, as “the linguistic sub discipline [sic] dealing with the scientific study of all aspects of written language.”[5] Dimitrios Meletis, in his landmark The Nature of Writing: A Theory of Grapholinguistics (2020), notes the discipline emerged as a remedy of sorts to the “implicit written language bias” (WLB) within the field of linguistics as identified by Per Linell.[6] This is important. Though a full discussion of the WLB is beyond the scope of this discussion, the gist of Linell’s point is that the field of linguistics tends to overlook the role of writing and writing systems even though writing itself is a form of active communication. Describing this reality in relation to speech, Linell writes,

[W]hile the processes involved in the production of written texts are usually not directly communicatively significant, the fact that the products persist over time makes various types of intermediary communicative acts available. The written texts can be used in different ways, edited and re-edited, re-employed, duplicated, distributed to particular persons or groups in new situations, and these activities can be regarded as proper communicative acts in their own right (or as parts of such acts). These acts are often instigated and performed by other people than the writer, the original sender, himself.[7]

The point here – much like the creation of a text-world resulting from some hand other than the author’s – is that written language is a communicative act whether intentional or not. It does not passively record language and serve only to transmit information. Indeed, on the point of the WLB, Meletis makes the important observation that written language itself likely enabled various forms of linguistic consciousness (e.g., the concept of phonemes, words, and the idea of a sentence).

Giving his definition of grapholinguistics, Meletis states,

Grapholinguistics not only aligns terminologically with designations used for other linguistic subdisciplines such as psycholinguistics and sociolinguistics but also originates and thus reflects the German-language [Schriftlinguistik] research area’s decades-old practice of acknowledging and investigating writing and written language in their own right rather than as secondary and peripheral matters of linguistics. Additionally, unlike the alternative designations listed above, it is not already occupied as a label for other disciplines or endeavors.[8]

Grapholinguistics is a subfield of linguistics interested in the way writing functions as writing, not (simply) as a vehicle for representing spoken language. A text-world, then, within the context of literature, becomes the object of study within the field of grapholinguistics. Here the boundaries between literature and linguistics begin to blur: if we are going to approach a literary text-world from a grapholinguistic perspective, then we must understand how that text-world relates to the world it is representing. The key is understanding how a particular text-world fits within the larger architectural integrity of a particular writing system, and how the adherence or deviation from orthographical norms relates to narrative content. Grapholinguistics can help us understand how that text-world is created and why it is able to relate to narrative content the way it does.

There will be challenges along the way. Grapholinguistics as a discipline must develop not only an architectural understanding of the world’s writing systems but also familiarity with how said writing systems represent language in a variety of contexts. Spoken language does not exist in a vacuum and neither does written language. Without such an understanding, any theories about how writing systems function will remain tethered still to the written language bias grapholinguistics is trying so hard to reject. Consider the way Meletis and Christa Dürscheid – scholars whose work I admire and support – describe the division of labor between hiragana and katakana and the function of furigana.

Synchronically, the two kana scripts fulfil different functions in the writing system: hiragana, the default kana, are used for writing grammatical information and are attached to the morphographic [Sinograph], which represent lexical roots. Also, in some texts, such as texts for beginning readers, [Sinographs] are not used at all as such texts are written completely in hiragana. Katakana, on the other hand, mostly serve to write foreign or borrowed words as well as foreign names and toponyms for which there are no [Sinographs]. Additionally, they are used for onomatopoetic expressions, to signify emphasis, or for technical and scientific terminology (cf. Smith 1996). A special use of kana is as so-called furigana, smaller kana – mostly hiragana, in rarer cases katakana – which are positioned above (when the writing direction is horizontal) or (in vertical writing) to the right of [Sinographs] to indicate their pronunciation. They are found predominantly in written materials intended for children or L2 learners.[9]

While not incorrect, the adverbs “mostly” and “predominantly” are doing heavy lifting here. They suggest that usages of hiragana, katakana, and furigana that deviate from normative and predictable – what might also be called “safe” – usages are either uncommon or innocuous. However, as we’ve seen throughout this series, this could not be further from the truth. It is important to point out that Meletis and Dürscheid are not fully to blame in this not-wrong-but-incomplete understanding of how written Japanese functions. Indeed, such descriptions are everywhere in secondary sources.[10]

Yes, it is true that “hiragana (…) are used for writing grammatical information and are attached to the morphographic [Sinograph],” and that “some texts, such as texts for beginning readers (…) are written completely in hiragana.” But what about those texts where hiragana is used to indicate the visual impairment of a protagonist as in Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s Shunkinshō (Portrait of a Blind Man, 1933), emotional vulnerability and intimacy as in Tanikawa Shuntarō’s poetry collection Hadaka (Naked, 1988), or the physical exhaustion of the narrator as in Machida Ryōhei’s One Round: 1:34 (2018)? Yes, it is true that katakana “mostly serve to write foreign or borrowed words as well as foreign names and toponyms” or “onomatopoetic expressions, to signify emphasis, or for technical and scientific terminology.” But what about those texts where katakana is used to suggest a pre-war worldview and value system as in Tanizaki’s Kagi (The Key, 1956), alienation and distance from the standard Japanese language as in so much of Sakiyama Tami’s literature, or chaos and destruction as in the insistence to write Hiroshima or Fukushima in this manner? Yes, it is true that furigana are usually “smaller kana – mostly hiragana, in rarer cases katakana – which are positioned [around Sinographs] to indicate their pronunciation” and are often “found in written materials intended for children or L2 learners.” But what about those texts where furigana is used to represent otherwise incomprehensible non-standard Japanese as in Inoue Hisashi’s Kirikirijin (1981), to incorporate visually jarring Korean linguistic interventions as in Lee Yangji’s Yuhi (1988), or a narrative revolting against the base text as in EnJoe Toh’s “Goji” (Mistaken Glyphs, 2018)? These text-worlds, each distinct, are the result of a particular worldbuilding process and are worthy of our attention.

A Short Conclusion

If grapholinguistics is to free the study of written language from the confines of linguistics it must also bring intentional uses of written language – that is, examples of written language serving as intentional communicative acts – into its purview. A study of how written language functions in literature will not only help the field of grapholinguistics develop in new ways, but it can also help us establish a new framework from which to approach literature. As Sontag taught us years ago, resisting the urge to interpret texts in obvious ways can open those same texts in unexpected ways and in unanticipated directions. Reject the abstract and focus on the text-world; look close enough and you might see something new.

[1] Hergenrader, Trent. Collaborative Worldbuilding for Writers and Gamers, Bloomsbury Academic, 2019: 17.

[2] Ibid.

[3] I say “usually” because there are numerous exceptions to this rule. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, Joyce’s Ulysses and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee are just two examples of non-normative text-worlds in English-language literature.

[4] I will not linger on the question of authorial intent. For an extreme but important example of how muddled authorial intent can get – and just how heavy-handed (but necessary) editors and critics can be – see the Introduction to Hamlet: The Texts of 1603 and 1623, eds. Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor, Arden Shakespeare, 2006.

[5] Martin Neef quoted in Dimitrios Meletis, The Nature of Writing: A Theory of Grapholinguistics, Fluxus Editions, 2020: 3.

[6] Meletis, 2. As cited in the previous installment, Linell argues this WLB led to “a paradox; it proclaimed the primacy of speech and spoken language, and yet it largely stuck to the traditional methods and models developed for the study of written language” (“The Written Language Bias [WLB] in linguistics 40 years after,” Language Sciences, Vol. 76, 2019: 3).

[7] Per Linell, The Written Language Bias in Linguistics: Its Nature, Origins and Transformations, Routledge, 2005: 20.

[8] Meletis, 3.

[9] Dimitrios Meletis and Christa Dürscheid, Writing Systems and Their Use: An Overview of Grapholinguistics, De Gruyter, 2022: 239.

[10] Consider, for example, the following explanation of hiragana, katakana, and furigana from Peter T. Daniels and William Bright’s highly influential The World’s Writing Systems (Oxford University Press, 1996). Though a fuller explanation than Meletis and Dürscheid’s, their definition still fails to capture the full diversity of the writing system: “Hiragana (…) grew out of an increasingly simplified set of cursively written [Sinographs] used as man’yogana (…). Typical Japanese texts are written in a mixture of [Sinographs] and kana, primarily hiragana. Hiragana is used for particles, auxiliary verbs, and the inflectional affixes of nouns, adjectives, and verbs—in sum, the grammatical elements of sentences. (…) Like hiragana, katakana derived from man’yogana. (…) The present forms and conventions of use for katakana were fixed in 1900, at the same time as hiragana. Katakana is used in contemporary texts to write foreign names and loanwords, onomatopoeic and mimetic words, exclamations, and some specialized scientific terminology. It is also used for words usually written in kanji or hiragana to give special emphasis, indicate an ironic tone, signal euphemisms, and the like; young people are particularly likely to incorporate katakana into their script mix, perhaps to give a “conversational” tone to their written productions (Nakamura 1983; Satake 1989, 1990). (…) Both scripts are used as furigana: small kana put to the side of or above kanji in order to indicate the pronunciation or meaning of the [Sinograph] used” (212-3).