今野真二

前回の末尾において「振仮名について考えるためは、振仮名が施されている漢字列と振仮名として施されている語との関係、両者の結びつきを観察する必要がある。両者の関係、結びつきは観察しているテキストが成った共時態及び、その共時態内の「文字社会」を視野に入れながら考察する必要があると考える」と述べた。今回は前回述べたことをふまえて明治期の振仮名について考えてみることにする。

まず、丹羽純一郎訳、服部誠一校閲『[欧洲/奇事]花柳春話』(明治11年刊)初編(以下、単に『花柳春話』と呼ぶ)の「本文」を掲げる。『花柳春話』の「本文」においては多くの漢字に振仮名が施されているが、ひとまず省いて示す。

室内ヲ覗ヘハ野叟少女ト二人相対シテ坐シ傍ラニ/唯一榻ヲ剰スノミ其貧窶一目シテ知ラルヘシ

(2p)

『花柳春話』は、イギリスのE.G.リットンの小説『アーネスト・マルトラバーズ』とその続編『アリス』とを丹羽純一郎が抄訳したもので、漢語を多く使った「漢文訓読体」で翻訳され、「漢字片仮名交じり」で印刷されている。「漢字片仮名交じり」は文字をどう使っているかということについての呼称であるが、それを「表記体」ととらえることにする。

「漢文訓読体」といっても、和語をまったく使わないわけではない。上記の範囲でいえば、「傍ラニ」の「傍」には「カタハ」と右振仮名が施されており、「傍ラニ」が「カタワラニ」という和語を文字化したものであることがわかる。漢字列「室内」には振仮名が施されていないので、漢語「シツナイ」を文字化したものであることになるだろう。そうであれば、漢語「シツナイ」と和語「カタワラニ」とは1つの文の中で共起してもおかしくないと「書き手」に判断されていることになる。

引用した「本文」の「榻」には右傍に「タフ」、左傍に「イス」と振仮名が施されている。そのことからすれば、ここで選択されているのは「トウ(榻)」という漢語で、その漢語の語義を左振仮名「イス」が説明していることになる。「貧窶」の場合は、右振仮名がなく、左傍に「ビンボウ」と振仮名が施されている。漢語「ヒンル(貧窶)」の語義は〈非常に貧しいこと〉で、これは漢語「ビンボウ(貧乏)」の語義と重なる。漢語「ビンボウ」は『後漢書』において使われていることが確認できるので、古典中国語といってよい。漢語「ヒンル」を使って左振仮名において「ビンボウ」と説明するのであれば、最初から漢語「ビンボウ」を選択することはできなかったのか、という疑問があるが、これはできなかったから「ヒンル」を選択したと推測する。早くから日本語の語彙体系内に借用されていたと思われる「ビンボウ」は漢語らしさを次第に失い、『花柳春話』の「漢文訓読体」の中では使うことができなかった。そのために『花柳春話』の「漢文訓読体」のいわば「固さの度合い」に見合った「ヒンル」を使い、ひろく語義が理解されている漢語「ビンボウ」で「ヒンル」の語義を補足説明したと推測する。89pにおいては漢語「ヒンキュウ(貧窮)」(右振仮名ヒンキウ)が使われている。上記の推測があたっているのであれば、左振仮名「ビンボウ」を付加した漢語「ヒンル(貧窶)」がもっとも付加情報を必要とする語、すなわち難易度という表現を使うならば、難易度が高い語で、情報を付加するために使われた漢語「ビンボウ(貧乏)」がもっとも難易度が低い語で、右振仮名のみの漢語「ヒンキウ(貧窮)」が両者の間の難易度の語ということになる。

振仮名が「(行間)注釈」として、振仮名が施されている漢字列についての「付加情報」を与えているとみるならば、その「注釈」や「付加情報」を正確に読み解くことによって、当該テキストについての理解、当該テキストを構成している言語についての理解は格段に深化することになる。また53pにおいては漢語「ヒンセン(貧賤)」が左振仮名「ビンボウ」を施されて使われている。漢語「ビンボウ」はやはり左振仮名として使われている。「ヒンセン(貧賤)」を加えると、「ヒンル(貧窶)」・「ヒンセン(貧賤)」>「ヒンキュウ(貧窮)」>「ビンボウ(貧乏)」という難易度が予想される。

村上快誠が編輯し、明治7(1874)年に出版されている漢語辞書『必携熟字集』の「貧」の條には次のようにある。漢字2字のもののみを示す。見出しに片仮名で施された振仮名は漢字列の直下に丸括弧に入れて示す。

貧院(ヒンヰン) マヅシキモノヲイレルバシヨ

貧孀(ヒンシヤウ)マヅシキヤモメ

貧人(ヒンジン) マヅシキヒト

貧窶(ヒンロウ) マヅシキコト

貧民(ヒンミン) マヅシキヒト

貧困(ヒンコン) マヅシクテクルシム

貧富(ヒンプ) ビンバウトカネモチト

貧交(ヒンカウ) イヤシキモノヽツキアヒ

貧窮(ヒンキウ) ビンバウ

貧賤(ヒンセン) ビンバウデミガヒクイ

貧乏(ヒンボウ) マヅシキ

貧家(ヒンカ) ビンバウニンノウチ

貧素(ヒンソ) ビンバウ

貧薄(ヒンハク) ビンバウ

貧羸(ヒンルイ) ビンバウノコト

「貧」を頭字とする2字漢語15が見出しとして採用されているが、そのうち7つは「貧」を和語「マヅシキ」で説明し、やはり7つが「貧」を漢語「ビンボウ」で説明している。そして漢語「ビンボウ」は和語「マヅシキ」で説明されている。このことから漢語「ビンボウ」は和語「マヅシキ」とともに見出しとなっている「漢語を説明する語」で、その「ビンボウ」が「マヅシキ」で説明されているのだから、(当然のことながら)両語の難易度は「ビンボウ」>「マヅシ」であることがわかる。

このことを抽象的に説明するならば、当該時期においては、漢語「ヒンル(貧窶)」「ヒンセン(貧賤)」「ヒンキュウ(貧窮)」「ビンボウ(貧乏)」和語「マヅシ」の間に「連合関係」が成立しているということになる。より具体的に説明するならば、上記のような語義の難易度差があることまで推測することができる。

『必携熟字集』の記述からは、「ヒンル」「ヒンセン」「ヒンキュウ」の間での語義の難易度差は、推測することも難しく、上記の推測があたっているかどうかは、なお慎重に考える必要があるものの、とにもかくにも推測ができたのは、辞書のように、編集が行なわれていない具体的なテキスト『花柳春話』の振仮名の観察、分析に依る。

稿者は辞書のように、なんらかの編集が行なわれているテキストを「辞書体資料」、編集が行なわれていないテキストを「辞書体資料」を一方において「非辞書体資料」ととらえ、テキストに2つのタイプを設定してきた(注1)。「辞書体資料」の観察、分析から得られる知見も、「非辞書体資料」の観察、分析から得られる知見もともに限定的であり、両者を必要に応じて組み合わせることによって、「事実」を超えた推測が可能になると考える。

『花柳春話』初編において、漢語が左振仮名として施されている例としては、他に「人寰」(左振仮名セケン:10p)、「樓上」(左振仮名ニカイ:19p)、「鑰」(右振仮名ヤク/左振仮名ヂヨウ:21p)「預備」(左振仮名ヨウイ:21p)、「意(左振仮名シンパイ)ト為スナカレ」(22p)、「律呂」(左振仮名チヤウシ:42p)、「恬然」(左振仮名ヘイキ:42p)「戯言」(左振仮名ヂヨウダン:45p)「講義」(左振仮名コウシヤク:50p)「得失」(左振仮名ソントク:52p)「概ネ」(左振仮名タイガイ:53p)「淹留」(左振仮名トウリウ:54p)「看護」(左振仮名カンビヨウ:64p) などがある。

ここでは漢語「ヨビ(預備)」に「ヨウイ(用意)」が左振仮名として施されている。やはり「ヨウイ」は「注釈」に使われるような語であったことがわかる。

「概ネ」は和語「オオムネ」を文字化したものとみるのが自然であろう。そうであれば、和語の「注釈」として漢語「タイガイ(大概)」が使われていることになる。『日本語学大辞典』の見出し「おおむね」をみると、副詞「おおむね」の使用例としては11世紀の訓点及び書陵部本の『類聚名義抄』、13世紀の『名語記』の例があげられ、それに続いてあげられているのは19世紀『和英語林集成』初版と尋常小学読本である。『日本語学大辞典』が使用例を示さないからといって、14-18世紀に副詞「オオムネ」が使われなかったことにはならないが、(何か特別な理由がないことを前提とするが)『日本語学大辞典』が使用例を採っているような文献には使用がなかった可能性はあるだろう。そのために、和語ではあるが、「注釈」が必要であった。そしてその「注釈」に漢語「タイガイ」が使われた。明治2年に出版され、それ以降出版された漢語辞書に大きな影響を与えたことが指摘されている『漢語字類』においては、この漢語「タイガイ」は見出しになっているが語釈には「オホカタ」とあって、「オオムネ」が語釈に置かれていない。

漢語「カンゴ(看護)」には漢語「カンビョウ(看病)」が左振仮名として施されている。「カンビョウ」は早くから日本語の語彙体系内で使われていた語であることが確認できる。一方、「カンゴ(看護)」の使用は新しいと思われ、『日本語学大辞典』は19世紀以降の使用例しかあげていない。

『花柳春話』初編には「繁茂」(右振仮名ハンモ/左振仮名ボフ々々)(1p)「蹣跚」(右振仮名マンサン/左振仮名ヒヨロ々々々)(23p)「潜然」(右振仮名サン/左振仮名ボロ々々)(24p)「喃々」(左振仮名ベチヤ々々々)(29p)などのようにオノマトペの類が左振仮名として施されている例がみられる。

翻訳をしていて「書き手」は「ヒョロヒョロ」「ボロボロ」というオノマトペを思い浮かべた。漢字を表音的に使って、「ボロボロ」を「暮露暮露」と文字化することはできなくはない。しかし、これを『花柳春話』の「漢文訓読体」に埋め込むとおそらくそこだけがおかしなものにみえるだろう。「ヒョロヒョロ」の場合は、漢字を表音的に使うとしても「ヒョ」にあてる漢字が難しい。こうなると、仮名で文字化するしかないことになるが、『花柳春話』においては、いわゆる自立語はほとんど漢字によって文字化されており、「ヒョロヒョロ」「ボロボロ」はやはり『花柳春話』の「漢文訓読体」になじみにくい。そこで、『花柳春話』の「漢文訓読体」をこわさない文字化として漢語「マンサン(蹣跚)」「サンゼン(潜然)」を使い、振仮名を施した、という可能性はあるだろう。これは「マンサン(蹣跚)」「サンゼン(潜然)」をそれぞれ「ヒョロヒョロ」「ボロボロ」と読ませる、ということとはかなり異なる。

まずは、文字化したい「内容」があって、「書き手」はその「内容」に応じた「表記体」を選択する。選択にあたっては、漢語をどの程度使用するかということが自然に「表記体」選択のポイントの1つになることが予想される。漢語は漢字で文字化するということを前提としておくが、漢語を多く使う「内容」であれば漢字を多く使うことになる。漢字を多く使うということになれば、和語も漢字によって文字化することが自然になる。逆に漢語をあまり使わないのであれば、テキスト全体の仮名の使用頻度がたかくなるのが自然であろう。このように、「内容」が「表記体」に自然にふかくかかわり、上記のように、いったん「表記体」が選択されれば、その「表記体」に合わせた語の選択、表記の選択が行なされていくことは自然なことと思われる(注2)。そうした双方向的な「みかた」が今後は求められるのではないだろうか。

86pの「咲語喃々(右振仮名セイゴナン々々)」では、漢語「ナンナン(喃々)」が左振仮名なしで使われている。これは、漢字列「喃々」を真ん中にして、片側に漢語「ナンナン」が、もう片側には和語「ベチャベチャ」が結びついているという、漢字列を軸あるいは核とした「連合関係」が形成されていることを窺わせる。漢語「サンゼン(潜然)」は右振仮名「サンゼン」を施されて32pにおいて使われている。振仮名は表記の枠組みの中で捉えられることが多いが、実際は語彙的事象とみるべきであろう。

文化が成熟し、他者に伝えたい「内容」が拡大すれば、従来の「かきことば」には収まりにくくなる。それを「フォーマルな内容」から「インフォーマルな内容」と表現するならば、「インフォーマルな内容」を語っていた「はなしことば」が「かきことば」にもちこまれるということでもある。狂詩、狂歌の「狂」、戯作の「戯」を「インフォーマル」とくくってしまうのは粗いかもしれないが、「内容」の拡大が言語の「拡大・変化」を促したとみることはできるだろう。それはちょうど、中国において、明代に白話小説がうまれたことと似寄っている。

従来からある「かきことば」に少しの「はなしことば」を混ぜ用いることはできるであろうが、その場合であっても、漢字によって文字化するとなれば、当該「はなしことば」と語義上重なり合う「かきことば」の文字化に使われてきた漢字列を使って表意的に文字化するか、漢字を表音的に使って文字化するかしかない。前者の場合、振仮名を施さなければ「はなしことば」を文字化していることが「読み手」にはきわめてわかりにくい。また漢字を使わないのであれば、仮名によって文字化するしかないことになる。

明治20年頃になって盛んになった「言文一致運動」を待つまでもなく、江戸時代にすでにこうした状況がうまれていた。

「喫驚」(13p)の右振仮名に「キツキヤウ」、左振仮名に「ビツクリ」とある。『日葡辞書』が「Biccurito」(ビックリト)を見出しにしているので、室町期には使われていた語と思われるが、いかにも「はなしことば」にみえる。古本『節用集』もこの語を見出しにしていないと思われる。古本『節用集』の見出しは「漢字列」といってよく、漢字によって文字化することができない、もしくは漢字によって文字化された「実績」があまりない語は(たとえばその語が存在していても)見出しにすることができない。ちなみにいえば『言海』はこの語を見出しにしていない。このことからすれば、大槻文彦の目にも「ビックリ」は「普通語」とは映っていなかった可能性がある。

こうした語が文字化される場合には、仮名によって文字化されることがもっとも自然で、実際に抄物などにおいても仮名によって文字化されている。「ビックリ」を漢語「キッキョウ(喫驚)」に使う漢字列によって文字化することは、「書き手」の工夫にみえるかもしれないが、「漢文訓読体」の「表記体」の中で、「ビックリ」を使うために、すなわち「ビックリ」をなんとか漢字によって文字化するためにうみだされた可能性も考えておく必要があるだろう。漢語「キッキョウ」が使われなくなり、漢字による文字化の「圧力」が弱まれば、「ビックリ」は再び仮名によって文字化されるようになる。

江戸期につくられて残されている文献は室町期に比べれば格段に多い。しかしそれでも明治期に比べれば少ないし限定されている。江戸時代の日本語についての知見は江戸期につくられたテキストの観察、分析によって得るのがもっとも自然であるが、その「江戸期につくられたテキスト」が限定されているとすれば、明治期につくられたテキストの観察、分析によって江戸期の日本語を窺うというアプローチがあってよいし、そのアプローチによって、江戸期につくられたテキストが限定されていることを補うことができると考える。江戸時代全体を1つの共時態とみるのでは時間幅がありすぎるかもしれない。そうであれば、幕末期を1つの共時態として設定し、それと明治期とを共時態として対照することによって、江戸時代の日本語、明治時代の日本語双方のありかたを、なにほどかにしても深く探ることができるのではないだろうか。振仮名をそうした探究の入口とすることは可能であろう。

注1:「編集」は共時態を超えて行なうことができる。例えば『日本語学大辞典』第2版は2000年から2002年にかけて出版されている。しかし、使用例としては『万葉集』の使用例も、夏目漱石の作品の使用例もあげている。辞書全体は、21世紀に編まれた辞書ということになるが、その辞書をかたちづくっている日本語すべてが21世紀に共時的に使われていた日本語ではない。この例においては、このことは自明のことに思われるが、室町期に編まれた『節用集』をかたちづくっている日本語すべてが室町期に共時的に使われていた日本語かどうか、ということになると一定の検証が必要になる。正宗本『節用集』のイ部人倫門には見出し「伊弉諾」「伊弉冉」が置かれている。それぞれ「イザナギ」「イゼナミ」と振仮名が施されている。これらが室町時代に頻繁に使われるような語でないことは(常識的な想像ではあるが)容易に想像できる。しかし、まったく使われなかった語と断定することもできない。正宗本『節用集』において「伊弉諾」「伊弉冉」が見出しとなっている、ということは「事実」ではある。この「事実」というとらえかたは、室町期に成った辞書において見出しになっている語は(広義の、という意識があるかどうか、そのことも不分明であるが)広義の「室町時代語」であるというとらえかたといってよいだろう。このとらえかたにおいては、共時態というとらえかたが曖昧になっている。

注2:稿者が子供の頃は、小学校の夏休みの自由研究課題で、夏休み中に採集した昆虫の標本を提出することがあった。いろいろな昆虫をつかまえて、子供なりに標本にして1つの箱に入れて提出する。自分の家の周囲で採集した昆虫が多いが、場合によっては帰省先で採集したものが入っていることもあった。しかしそういうことは一切問題にはならない。生育している空間が異なるということは生態系が異なるということで、この「標本箱」の中には生態系が異なる昆虫が混在していることになる。それでも、採集が難しい昆虫が並んでいれば、がんばったね、とほめてもらえた。生態系は言語の共時態に重ねることができるだろう。珍しい「漢字列+振仮名」をきりとって集める、あるいはどのような「表記体」のテキストの中にあったかということを離れて振仮名が論じられることが少なくなかったと、自戒をこめて述べておきたい。振仮名はある共時態に属している「書き手」と「読み手」の「連合関係」を背景にして成り立っているとみるべきではないだろうか。

Konno Shinji, trans. Chris Lowy

Chapter 01: What is Furigana?

Before embarking on our journey into the long history of furigana it will be useful to examine how furigana is used today. Though today furigana are rarely used in newspapers and magazines, there are still a variety of furigana types in common usage witnessed in other contexts. In this chapter I consider useful ways of thinking about and approaching furigana by citing actual examples from contemporary sources. Consider this a warm-up stretch before starting our actual trek into the history of furigana.

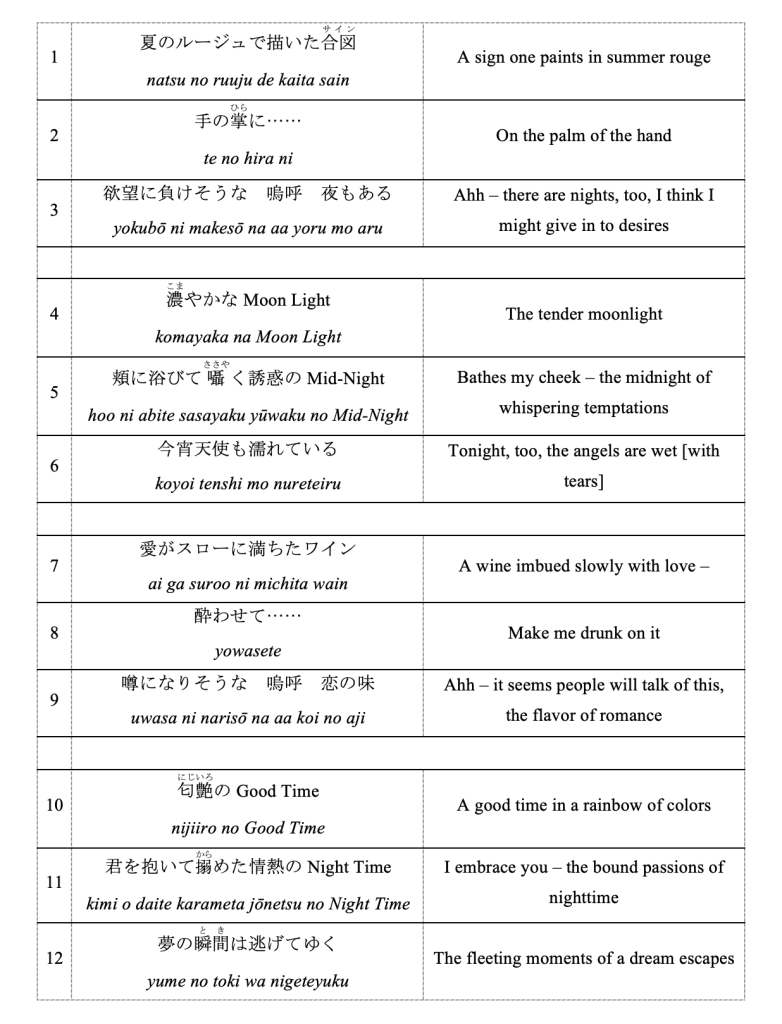

These lyrics from Southern All Star’s song “Moon Light Lover” are taken from the official lyric book included with its release album. In terms of written Japanese, the lyrics include Sinographs, hiragana, katakana, and the alphabet.[1] Today, writing a single Japanese text in various character sets is wholly unremarkable; indeed, it is neither strange nor especially noteworthy. The act of writing Japanese with multiple character sets is also profoundly related to furigana. This will become clear throughout the course of this book.

Who are Lyric Sheets for?

If you think about it, lyric sheets are strange things. Lyric sheets – which used to be inserts in albums but today are found in (the increasingly rare) CDs – are, of course, tools for learning and understanding the lyrics of a song. We’ve all been there before: you listen to a song and just can’t understand what the singer is singing. Just then, you pull out the lyric sheet and, aha, that’s what he’s belting out! In the case of Kuwada Keisuke, the lead singer of Southern All Stars, a lyric sheet could be critically important to understanding him because his manner of singing is what distinguishes him as an artist. If, however, the goal was simply to show the words coming out of an artist’s mouth then lyric sheets could be written in all katakana. For example, the first line of the above lyrics could be written phonetically as ナツノ ルージュデ カイタ サイン. In fact, though, I’ve never seen lyrics written this way and it is not the norm. This suggests that lyrics do more than simply provide the reader/listener with the words of a song. Rather, instead of lyric sheets being simply a record of the sounds escaping from an artist’s mouth, they are written representations of the words that comprise those lyrics. Lyrics are more than just the words of a song; they are works of art on par with, for example, contemporary poetry. We might even go so far as to say that a song in the broadest sense is born from the marriage of a musical composition and its lyrics, with lyrics themselves possessing a written form of representation.

A Multitude of Possibilities in Written Japanese

A cursory listen reveals that komayaka na muunraito are the lyrics to line four. Looking at the lyric sheet we see the author wanted to write komayaka not in the standard 細やか but濃やか, and that they wanted to write muunraito not in the expected katakana ムーンライト but in the alphabet and in English. On the other hand, we see they wanted to write rouge (ruuju) not in the alphabet but in katakana, and sign (sain) not in katakana as サイン or in the alphabet but rather in a combination of Sinographs with furigana as 合図. Earlier I said these lyrics are written in a combination of Sinographs, hiragana, katakana, and the alphabet; in fact, the same thing can be said regarding individual words.

For example, aidoru (idol), a word of foreign origin used regularly in Japanese today, can be written in katakana as アイドル, in hiragana as あいどる and, even if rare, in Sinographs phonetically as 阿伊度留or together with furigana as 偶像. Of course, one could also write it using the alphabet as aidoru. In other words, within the space of written Japanese there are no fundamental rules dictating how something must be written. If we call such hard and fast rules an orthography, then it stands to reason that written Japanese lacks an orthographical standard in the same way it exists in, for example, English. Today, if we were asked to write アイドル (idol) in English we have one choice – idol – and all other attempts would be viewed as erroneous. When compared to this inflexibility it is clear there are multiple “correct” forms to write individual words (and thus sentences and complete texts) in written Japanese. This also means that for an author there exits more than one option for the written representation of language.

“I Want to Write in Sinographs!”

Sinographs developed in China as characters to write the Chinese language. Since Japanese lacked a dedicated set of natively derived characters to write the Japanese language, early interactions between Japan and the highly developed culture of China led to a borrowing of Sinographs from China to write the Japanese language. It is important to note that the Chinese languages in all their varieties are vastly different from the major languages of Japan: while Chinese languages are classified as members of the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, the Japanese language(s) are generally considered to be language isolates. This is important to note because while Sinographs developed to write the Chinese language, the different linguistic structures between Chinese and Japanese meant that significant adaptations needed to happen before those same characters could be used to write Japanese in ways that reflected, for example, verbal inflection.[2]

Kana (both hiragana and katakana), specialized characters used to write the Japanese language, developed after a relatively short period of time from the first interactions between Japan and China described above. Once the Japanese linguistic space acquired these kana there should have been the option to cease use of the borrowed Sinographs. However, texts written in the post-kana acquisition period are not usually written exclusively in kana, and today, too, Sinographs are integral parts of written Japanese. Put another way, Sinographs were not abandoned.

We might also think of this decision to not cast aside Sinographs thus: until the acquisition of kana there was enough accumulated experience of writing Japanese via Sinographs that the idea of getting rid of them seemed unnecessary. It’s natural to imagine this is how things played out, but we can take it one step further and imagine it being viscerally difficult to toss Sinographs aside. Put more plainly, there might have been a strong desire to not get rid of them. In other words, and in a variety of senses, there was (and still is) a deeply rooted desire to write in and with Sinographs. This desire to use Sinographs is another key to understanding furigana. If we write the word English word “sign” in katakana as サイン (sain) there is no need for furigana. If, however, we desire to write “sign” with the Sinographs 合図 then furigana become indispensable.

Two Languages

Given that Sinographs were originally used to represent the Chinese language, it is impossible to separate the act of writing Sinographs from the Chinese language. Since they are inseparable from Chinese, when we use them to write Japanese, they are simultaneously playing an important role in two languages (and, in fact, any language that utilizes Sinographs). This reality of dual languages, too, is important to the furigana context.

A different song by Southern All Stars, “Nijiiro – The Night Club,” contains the following line: 匂う女の舞うトルバドール. Here, the most predictable way of writing the term troubadours – we would expect troubadours – has been inverted. First, the French word troubadours is written in katakana (トルバドール), with the French alphabetic spelling supplied as furigana. The two languages of French and Japanese thus coexist in this space, with the French term appearing in its usual alphabetic representation and the Japanese term appearing in its usual katakana representation. These two writing systems are combined and used side-by-side with each other.

When there is a need to write a non-Japanese term in a Japanese-language environment one has the choice to write that language in either kana or Sinographs. There is also the option to write the term in a writing system not generally used to write Japanese. All these possibilities are witnessed in the lyrics presented thus far.

Furigana-as-Readings

In the lyrics the Sinographs 夏 (natsu; summer) and 夢 (yume; dream) appear without furigana. According to the List of Sinographs by School Year (学年別漢字配当表), which lists 1,026 characters and is included in the Ministry of Education’s Curriculum Guideline for Elementary School (小学校学習指導要領), 夏is to be taught in the second year of elementary school and 夢 in the fifth year. Thus, from today’s perspective, anyone who has studied beyond the fifth year of elementary school would not need furigana to read these Sinographs, with “read” here meaning both to pronounce correctly and understand its meaning. Put a bit more strongly, as a result of today’s educational policy the relationship between the Japanese terms natsu and yume and the Sinographs 夏 and 夢 is firmly established, so the use of furigana is deemed unnecessary. Similarly, the Sinograph 山 (yama; mountain) is learned in the first year of elementary school and so it is extremely rare to see furigana attached to it. This is because the connection between the Japanese term yama and the Sinograph 山 is widely recognized and thus incredibly stable. Even the poems of the ca. 8th-century Man’yōshū that include the word yama writes the term, almost without exception, simply as 山.

Let’s think about this from the opposite angle: if Sinograph Y is used to write Japanese term X but the relationship between X and Y is not widely recognized – if the connection between the two is not stable – then the reader of a text will see Sinograph Y and not immediately associate it with Japanese word X. A fan of Southern All Stars might see (Y) 匂艶 (lit., “a fragrant attraction”) and understand it corresponds to (X) nijiiro (“iridescent”), but an average reader would have no idea this is the case. Outside of this extremely limited audience the term is unreadable. Thus, when the relationship between Sinograph Y and Japanese term X is weak, it becomes necessary for the author of a text to let the reader know Y is writing X by using furigana to visualize its reading.

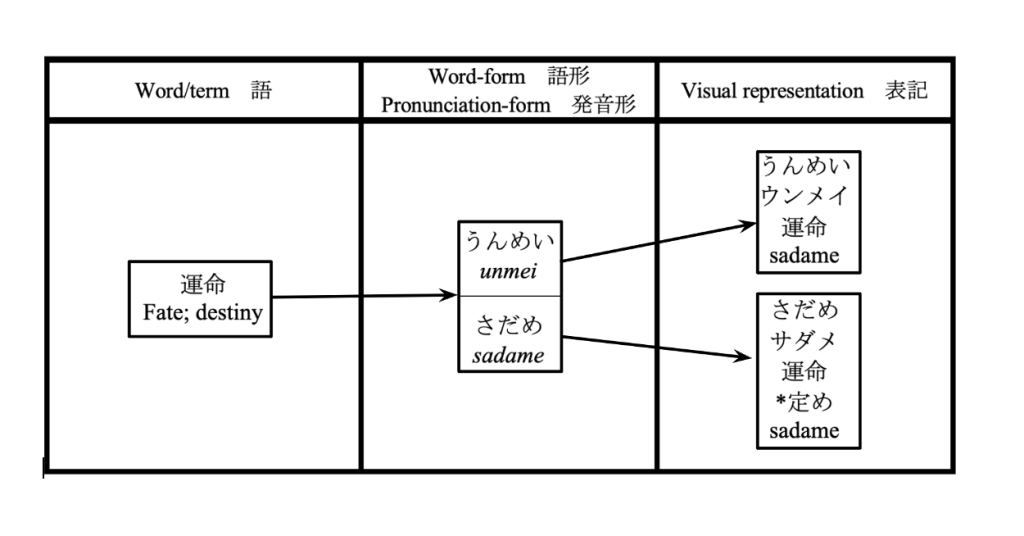

In this scenario we can refer to such furigana as furigana-as-readings (読みとしての振仮名). Because the term “reading” harbors some ambiguity, it is best to think of these furigana-as-readings as specifying the word-form of a Sinograph.

Now, what do I mean by word-form (語形)? Imagine you step into a classroom and on the blackboard is written two Sinographs: 運命, meaning “fate, destiny.” If I asked what word (語) this character-string was writing, you would, in fact, have no way of knowing. You might assume it was unmei, a word of Chinese origin, when it might in fact be sadame, a word of Japanese origin. In other words, without context, the word-form of 運命 is in a state of ambiguity, but write unmei in hiragana or katakana and, in that instant, it’s word-form becomes settled. We might think of word-form as being synonymous with a pronunciation-form (発音形). Without any additional context, if one is asked to read 運命, both unmei and sadame would be correct answers. In situations like this where numerous readings are imaginable its word-form is not decided. My use of the term word-form in this study is consistent with what I have outlined above. Word-form, too, is integral to thinking about furigana. In the chart below I have organized these terms.

Furigana-as-readings are, naturally, closely connected to who is reading a text, that is, a text’s readership. For example, furigana will be attached to all Sinographs in reading material and manga that early primary school students have a high likelihood of reading. It is for this reason that all Sinographs have furigana attached to them in Shueisha’s famous manga journals Weekly Shōnen Jump and Ribon.

Limited Sinograph Usage and the List of Sinographs in Common Use

In 2010 the Japanese government accepted a report issued by the Ministry of Education and based on their recommendations published a list of 2,136 Sinographs and associated readings that are to be taught in primary and secondary schools. This list, called the List of Sinographs in Common Use (常用漢字表), added an additional 196 Sinographs to an already-established list of 1,850 Sinographs. These Sinographs and the readings included in the list are today standard, the process of standardization resulting from these very governmental policies. We might regard this situation as an artificial one in which restrictions have been applied from the outside onto Sinograph usage, the virtues of which I will not argue here. It also follows that the List of Sinographs in Common Use creates, in a sense, a set of characters recognized by society at large. At the same time, while the use of Sinographs that fall outside of the List of Sinographs in Common Use – i.e., Sinographs that are not officially “recognized” – is not uncommon, use of these Sinographs necessitates some form of special care. One form of such special care is, you might have guessed, furigana.

In the lyrics from earlier we find 囁く (sasayaku; to whisper), where 囁 is not included in the List of Sinographs in Common Use. The Sinograph 搦 (to bind), too, is not part of this list. While 濃 is included, the only Japanese reading provided in the list is koi (dense, concentrated, deep), not komayaka (rich [color], tender, thoughtful). Today, these readings existing beyond the boundaries of the List of Sinographs in Common Use often appear with furigana attached to them. Note that in all cases furigana have been used to visualize and disambiguate these non-recognized readings.

Furigana-as-Expression

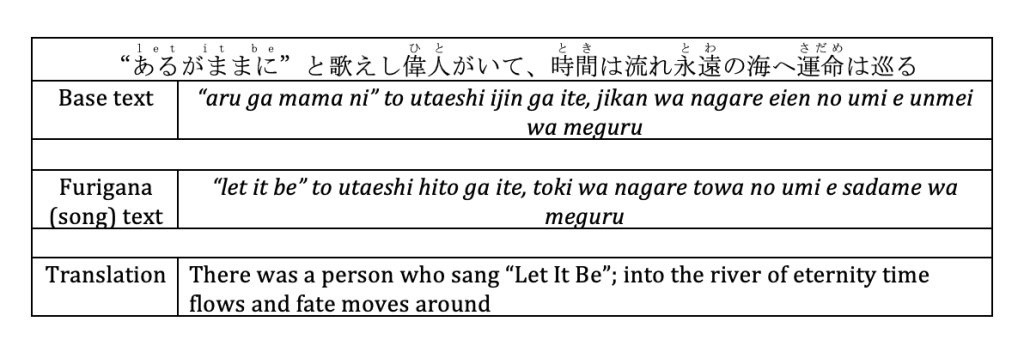

The lyrics to Southern All Star’s song “Suteki na yume o kanemashо̄”(Let’s Make your Wonderful Dream Come True) contains the following line:

The English phrase “let it be” is written in the alphabet and appears as furigana attached to あるがままに. Here both English and Japanese appear together, another example of two languages and scripts occupying the same space. However, it is aru ga mama ni that is sung aloud; strictly speaking, the furigana of this line, “let it be,” is not necessary.

Considering this, then, the furigana “let it be” is different from furigana-as-readings (or furigana that demonstrate a word-form). In this way we might consider its placement superfluous, something more akin to a furigana-as-expression (表現としての振仮名).

Yume no toki is written 夢の瞬間 in “Moon Light Lover.” If the author would have written 夢の時 there would have been no need for furigana. But he didn’t: the author wanted to represent the Japanese term toki with the two-character Sinograph string 瞬間, which would typically be read as shunkan. This desire to write a term in a particular way is a proactive decision to represent language in an expressive (or visual) manner. On the one hand is the desire for such representation and on the other is the reality that 夢の瞬間, if left unannotated, would in all likelihood be read yume no shunkan. Thus, the furigana in 夢の瞬間 is essential.

This is one line of thought, of course, but is it as simple and straightforward as that? It seems that in the conscious act of writing toki as 瞬間 is an intentionality to superimpose the two-character Sinographs of Chinese origin 瞬間 with the Japanese term toki, resulting not in a straightforward connection between Japanese term X and Sinograph Y (e.g., toki = 時) but in a multifaceted expression that expands outward into multiple directions. This is what I refer to ss furigana-as-expression. 時間 (toki; time), 永遠 (towa; eternity), and 運命 (sadame; fate, destiny) are all examples of this.

In this first section I proposed some concepts that will help us to think about furigana by citing examples from the published lyrics of songs by Southern All Stars. In the next section I will further my discussion of furigana by examining various uses of furigana in contemporary fiction.

[1] [Konno uses the word “alphabet” here and throughout this chapter. Broadly speaking, it can refer to using the alphabet to either write English and any other foreign language as well as recording Japanese in the alphabet. The latter is generally referred to as romanization, though I have not been strict in differentiating between the two.]

[2] [I have added some linguistic context to this section. Though the Chinese and Japanese languages may seem superficially related due to their shared use of Sinographs, the various typological differences between the two are, in large part, what led to many of the architectural features of written Japanese. For more on the impact these typological differences had on the development of writing in East Asia generally, see Zev Handel’s Sinography: The Borrowing and Adaptation of the Chinese Script (2019).]