今野真二

「かきことば」を「文字言語」と言い換えると、文字によって可視化された言語ということになる。「互換」を〈互いに換えること〉あるいは〈互いに換えることが可能なこと〉ととらえると、表題は「文字言語の互換性」あるいは「文字言語に互換性があるかどうか」ということについて論じることになる。〈互いに換える〉=互換は、そもそも2つ以上の文字言語がなければ、観点自体が成立しない。

日本語の場合、9世紀末頃に仮名が発生してからは、表意文字である漢字と表音文字である仮名(片仮名・平仮名)とを使って文字化を行なっている。片仮名と平仮名とを「仮名」としてくくるのであれば、「漢字・仮名」の2種類、片仮名と平仮名とを別の文字とみれば、「漢字・片仮名・平仮名」という3種類の文字を使って文字化を行なっていることになる。

ある語Xを、どの文字を使って文字化しても「まったく同じ」であるならばその言語の「かきことば」においては100パーセント互換性があることになる。ただし「まったく同じ」の「同じ」は何が同じなのかということについてはよく考えておく必要がある。

今野真二『振仮名の歴史』(2009年、集英社新書、2020年に「補章」と「現代文庫版あとがき」を加えて岩波現代文庫として刊行)の「おわりに」において、夏目漱石の全作品を3巻に収めたことを謳う、ウーブル・コンプレート『夏目漱石全集』(1965年、春陽堂書店)の『虞美人草』の本文を採りあげた。ここでは、同じウーブル・コンプレート『夏目漱石全集1』の『それから』の末尾を具体例としてあげてみよう。

たちまち赤い郵便筒が目についた。すると、その赤い色が、たちまち代助の頭の中に飛び込んで、クルクルと回転し始めた。かさ屋の看板に赤いこうもりがさを四つ重ねて、高くつるしてあった。かさの色が、また代助の頭に飛び込んで、クルクルとうずを巻いた。四つかどに、大きいまっかな風船玉を売ってるものがあった。電車が急にかどを曲がるとき、風船玉はおっかけてきて、代助の頭に飛びついた。小包み郵便を載せた赤い車がハッと電車とすれ違うとき、また代助の頭の中に吸い込まれた。タバコ屋ののれんが赤かった。売り出しの旗も赤かった。電柱が赤かった。赤ペンキの看板が、それからそれへと続いた。しまいには、世の中がまっかになった。そうして、代助の頭を中心として、クルリクルリと炎の息を吹いて回転した。代助は、自分の頭が焼け尽きるまで、電車に乗っていこう、と決心した。

(1078-1079p)

この箇所を漱石は自筆原稿に次のように文字化している。振仮名をはずして示す。

忽ち赤い郵便筒が眼に付いた。すると、其赤い色が忽ち代助の頭の中に飛び込んで、くる々々と回轉し始めた。傘屋の看板に、赤い蝙蝠傘を四つ重ねて高く釣るしてあつた。傘の色が、又代助の頭に飛び込んで、くる々々と渦を捲いた。四つ角に、大きい眞赤な風船玉を賣つてるものがあつた。電車が急に角を曲るとき、風船玉は追懸て来て、代助の頭に飛び付いた。小包郵便を載せた赤い車がはつと電車と摺れ違ふとき、又代助の頭の中に吸ひ込まれた。煙草屋の暖簾が赤かつた。賣り出しの旗も赤かつた。電柱が赤かつた。赤ペンキの看板がそれから、それへと續いた。仕舞には、世の中が眞赤になつた。さうして、代助の頭を中心としてくるり々々々と燄の息を吹いて回轉した。代助は、自分の頭が焼け盡きる迄、電車に乗つて行かうと決心した。

自筆原稿もウーブル・コンプレート版の「本文」も声に出して読めば、「同じ」といってよいだろう。すなわち「音声言語」としては「同じ」ということになる。上の2つを読んで録音した場合、どちらを読んでも録音されたものは同じということである。この「同じ」をもって自筆原稿とウーブル・コンプレート版の「本文」には「互換性」があるとみなすことはできる。それは、「音声言語」化した時に「同じ」になるかどうかをscaleとするということになる。

さてそれでは、「たちまち」と「忽ち」、「赤いこうもりがさ」と「赤い蝙蝠傘」とは「同じ」であるか、あるいは「クルクル」と「くるくる」とは「同じ」であるか、と問われた時に、どう答えるだろうか。何の迷いもなく「同じ」だと答える人もいるであろうが、少し「異なる」ように感じる人がいる可能性はあるだろう。しかしまた、「異なる」と感じた人であっても、自身がどう「異なる」と感じているかを言語によって第3者が理解できるように説明できる人が少ないことも予想される。「異なっているように感じるが言語によってうまく説明できない」というのはどういうことだろうか。

「言語によってうまく説明できない」ことを第3者が理解することは通常は難しい。しかしまた、「言語によってうまく説明できない」が「異なる」と感じる人が一定数いるとなると、説明はできないけれども「違い」はある、とみなすこともできなくはない。

このことがらを言語学・日本語学の枠組み内で論じるのであれば、「言語によってうまく説明できない」「違い」はそもそも共有できないのだから「違い」はない、とみなすのが「常道」であろう。事象について過剰に心理的なみかたを採らないという点において、その「みかた」を「合理的」と評価することができるかもしれない。そして、それを「合理的」と表現すると、「言語によってうまく説明できない」「違い」があることを認めることは「非合理」ということになる。「非合理」はそのまま「非科学的」ということになりそうではあるが、「非合理」「非科学的」は「合理」「科学」をどのように定義するかによって定義が変わる(注1)。

上記のことは、人間を介在させない合理的な言語学・日本語学では「違い」はなく、人間を介在させた「不合理」な「みかた」においては「違い」があるといういいかたができるかもしれない。

さて、少し話題を展開してみよう。文字化はまずは語を単位として行なわれると考えたい。そして、1つの語を文字化して、その言語活動が終わるということは通常は考えにくく、語は「文」をつくるために選択され、文字化されることが一般的であろう。そうであれば、「語の文字化」に「文の文字化」「文章の文字化」「テキストの文字化」が続いていくことになる。ここでは便宜的に、「語の文字化」と「文・文章・テキストの文字化」とを分け、後者を「テキストの文字化」に代表させて述べていくことにしたい。「テキストの文字化」は結局は当該テキストがどのような「表記体」であるか、ということと重なり合う。「表記体」は「言語がどのように文字化されているか」ということによって決まると、簡単に定義しておくことにする。

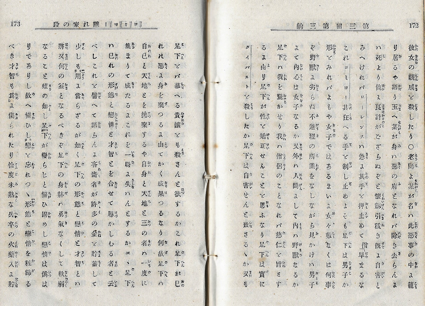

図1は明治19(1886)年に出版されたボール表紙本、河島敬蔵翻訳『春情浮世之夢』再版(明治20年出版)の172-173p。テキストは「漢字平仮名交じり」の「表記体」で文字化されている。「漢字片仮名交じり」の「表記体」ではないことは、「漢文訓読」調の「文体」ではないことをひとまず想像させる。「文体」も「表記体」も漢語をどの程度使うかということとかかわると考えるが、両者の関係をどのようにとらえればよいかについては、今ここではふみこまないことにする。

172pでいえば、「シンセキ(親戚)」「ロウシ(老師)」「アクジ(悪事)」「アク(悪)」「フ(府)」「カイケン(懐剣)」「ジガイ(自害)」「キュウ(急)」「セイ(制)」「ヤジュウ(野獣)」「ドウリ(道理)」「ナイシン(内心)」「ニンゲン(人間)」「ソウリョ(僧侶)」「ジジン(慈仁)」「セイ(性)」「キョウセイ(矯正)」という漢語が使われている。現代日本語でも使われている漢語が少なくない。『春情浮世之夢』が漢語をある程度使う以上、文字化に漢字を使うことになるのは自然であろう。そして漢語は漢字によって文字化される。

そう考えると、『春情浮世之夢』のような「漢文訓読」調ではない、「漢字平仮名交じり」の「表記体」を採るテキストにおいては、和語がどのように文字化されているかを観察することが重要になる。『春情浮世之夢』の「本文」が仮名で文字化しているが、漢字によって文字化できそうな箇所を以下に示し、右側には漢字を使った文字化の可能性を示してみることにする。

1:既に自害とみへければ (172-4) 見へければ

2:我は僧侶のことなれば (172-9) 事なれば

3:性を矯正せんことを思ふなり(172-10) 矯正せん事を思ふ也

4:これ足下が己れの (173-1) 是

5:かく成果つるなり (173-2) 斯く成果つる也

6:軟弱なること蠟の如し (173-9) 軟弱なる事蠟の如し

あまり多くはない。このことからすれば、『春情浮世之夢』はある程度漢字を使って文字化しようとしているテキストとみることができる。172pには「野獣(振仮名やじう)」と「野獣(振仮名けもの)」が隣接してみえる。また173pには「己(振仮名おの)れ」(1行目)「自己(振仮名おのれ)」(2行目)「自身(振仮名おのれ)」(2行目)、「形態(振仮名すがた)」(5行目)「形態(振仮名かたち)」(7行目)、「戀情(振仮名れんじやう)」(5行目)「戀情(振仮名こひ)」(7行目・9行目・10行目)、「戀(振仮名こひ)」(10行目)があって、漢語「ヤジュウ」と和語「ケモノ」とがともに漢字列「野獣」によって文字化され、和語「オノレ」が漢字列「己」「自己」「自身」によって文字化され、漢語「レンジョウ」と和語「コイ」とが同一の漢字列「戀情」によって、また和語「コイ」が漢字列「戀情」と「戀」とによって文字化されている。わかりにくいので簡単な整理をすると次のようになる。

漢語「ヤジュウ」・和語「ケモノ」……漢字列「野獣」

和語「オノレ」 ……漢字列「己」「自己」「自身」

漢語「レンジョウ」・和語「コイ」……漢字列「戀情」

和語「コイ」 ……漢字列「戀情」「戀」

1pの中で、漢語「レンジョウ」と和語「コイ」とを使っていることに関しては、そもそも漢語と和語とで語そのものが異なるのであるから、「文」をかたちづくる語の選択において、ある文では「レンジョウ」が選択され、ある文では「コイ」が選択されたということはあり得る。しかしまた、「足下(振仮名ごへん)が變(振仮名かわ)らじと誓(振仮名ちか)ひ固(振仮名かた)めし戀情(振仮名こひ)は偽(振仮名いつ)はりでありし故(振仮名ゆ)へ誓(振仮名ちか)ひし戀(振仮名こひ)を忘れつゝ形態(振仮名かたち)と戀情(振仮名こひ)を粧飾(振仮名かざ)るべき才智(振仮名さいち)も為(振仮名ため)に傷(振仮名やぶ)られたり」においては、1つの「文」において3回使われている「コイ」を「戀情」「戀」「戀情」と文字化しており、現代日本語を母語とする観察者・分析者はこうしたことを「書き手」が「意図的」に行なっていると想像したくなる。しかしその「意図」は何かと考えた場合、文字化に変化をつける、ということ以外には想像できることはないだろう。先に示した、「オノレ」を「己」「自己」「自身」と文字化することも同様にみえる。

語をどのように文字化しても、何も「違い」がないのであれば、「文字化に変化をつける」必要はない。したがって、述べてきたことが「文字化に変化をつける」ことを意図して行なわれたのであれば、「戀情(振仮名こひ)」と「戀(振仮名こひ)」とは、選択している語は「コイ」で「同じ」であっても、前者と後者とでは何かが「違う」ことになる。

語義に関して「明示的意味」と「副次的意味」とを分けるとらえかたがある。これに倣えば「戀情(振仮名こひ)」と「戀(振仮名こひ)」とは明示的には「同じ」であっても「副次的」には「異なる」ことになる。そしてそう考えると、次にはやはり「何が異なるか?」ということになる。

漢字を使って文字化するか、漢字を使わないで仮名で文字化するかということに関しては、言語学(日本語学)として、説明できることはあると考える。日本語をあらわすために使う漢字は表意文字で、仮名は表音文字であるので、漢字を使って文字化すれば、(たとえ漢字を表音的に使ったとしても)そこに意味、あるいは意味的なもの、が浮かび上がる。「読み手」はその浮かび上がった意味、意味的なものを感じないでいることが難しい。

澤崎文(2019[2020])が『万葉集』の文字化に使われている、いわゆる「音仮名」について「そこに用いられる音仮名は、結果的に日本語の音節をあらわす機能を有してはいても、用いられる前提としてその文字の訓字としての訓や意味が意識されており、音節のみをあらわすための単なる記号としては考えられていないことになる。「用法における文字」としては表音的に用いられていても、「素材としての文字」として表意性を内在させているという意味で、そのような文字は完全な音節文字としての記号にはなり得ない」(161p)と述べていることは首肯できる。しかしまた、中国語をあらわす表語文字としてうまれ、日本語をあらわす文字として使われるようになる過程で、表意的にも表音的にも使われようになった漢字にもしも人格があるのだとすれば、「そのような文字は完全な音節文字としての記号にはなり得ない」と言われた時に、自分は「完全な音節文字としての記号」になりたかったわけではない、と言い返すことはないのだろうか。つまり「なり得ない」という「みかた」は「合理的」にはそのとおりであったとしても、それは現代日本語を母語とする観察者・分析者の「みかた」であるということはないのだろうか。

亀井孝(1991[1995])は「万葉がなは、その本質において、かなではなく漢字である」(20p)「『万葉集』の作家たちは漢字で日本語の詩を書いたのである。もちろん、ここに漢字でというのは、第一義的には、漢字をその手段としてのいいである。しかしながら、詩というものは、表現を自己目的とするところに成立する。詩の表現にあたって文字をもまたその媒材としての存在にとどめしめず、これをその表現活動そのものの目的に転換してみるという、そのような実験を自覚的にこころみるいとなみは、詩、つまり作品を想像するその精神にとってとうぜんゆるされていいわざである」(20-21p)と述べている。「作家たち」はひとまずは「筆録者たち」と言い換えておくことにするが、「筆録者たち」は、漢字を表意的に使うにしても、表音的に使うにしても、「漢字で日本語の詩を書」いている、漢字を使って日本語のウタを文字化しているということは意識していたとみるしかなく、澤崎文(2019[2020])の「みかた」は先に述べたこととかかわらせるならば、そうしたことから離れた「合理的」な側にあるように思われる。

さて、さらに話題を変えることにしたい。室生犀星の「聖ぷりずみすとに與ふ」という序のような文章を巻頭に置いて、大正4(1915)年12月ににんぎよ詩社から発行された、山村暮鳥の『聖三稜玻璃』には「風景」というタイトルで「純銀もざいく」という副題をもつ次の詩が収められている。詩そのものはよく知られているだろう。

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

かすかなるむぎぶえ

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

ひばりのおしやべり

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

いちめんのなのはな

やめるはひるのつき

いちめんのなのはな。

一方、詩集『聖三稜玻璃』は「囈語」と題された次のような作品から始まる。

竊盗金魚

強盗喇叭

恐喝胡弓

賭博ねこ

詐欺更紗

瀆職天鵞絨(振仮名びらうど)

姦淫林檎

傷害雲雀(ひばり)

殺人ちゆりつぷ

堕胎陰影

騒擾ゆき

放火まるめろ

誘拐かすてえら。

「囈語」においては、漢字によって文字化された語と平仮名によって文字化された語とが微妙なバランスを保ち、「風景」においては、漢字を使わないことによって、意味の世界を離れた「風景」が浮かび上がる。この詩作品において「いちめんのなのはな」と「一面の菜の花」とが「同じ」であるとはもはや言えないだろう。ある時期以降という限定はあるかもしれないが、文字を使った「表現」は確実にあるといわざるをえない。

注1 亀井孝(1971[1986]は「ことば(=表現)をそのまま人間の歴史としてとらえる」みちと「表現の秘密を人間に君臨する記号の体系へまで抽象してゆく」みちと2つのみちがあることを述べた上で、「前者が厳密な意味での(狭義の)科学にならないことは、いうまでもない。それは事実(=歴史的事実)を記述するが、説明はしない。資料に対して解釈はほどこすが、原理の憲法をさだめて以て理論のわくを構築するのたちばとはしょせんはだがあわない。(音韻論において〝音韻論的解釈〟といわれているものは、ここにいう意味では説明であって解釈でないことも、ここに付言しておいてむだではあるまい。)したがって、もし後者を(形式主義の倫理学における道徳律に比すべき)記号のいわば至上命令をときあかそうとする合理主義であるとするならば、前者は人間のことばのいとなみをそのまま人間の(非合理の)生のその一つの客観化された形態としてとらえてゆこうとするもの、哲学の用語をかりていえば、すなわち合理主義に対する非合理主義のたちばにほかならない。そして、このようなちがいは、もともと科学と歴史とのその本質のちがいに根ざすものとみてよいであろう」(5p)と述べている。この言説において、亀井孝は「非合理主義」を否定していないと思われる。

参考文献

亀井孝 1971 「言語の歴史」(岩波書店、服部四郎編『言語の系統と歴史』所収、後1986年吉川弘文館『亀井孝論文集5』再収、引用は後者による)

亀井孝 1991 「『万葉集』はよめるか」(『成城萬葉』第22号、後1995年、吉川弘文館『ことばの森』に再収、引用は後者による)

澤崎文 2019 「漢字の表意性から見たかなの成立」(2019年、三省堂『万葉仮名と平仮名-その連続と不連続-』所収、後2020年、塙書房『古代日本語における万葉仮名表記の研究』に再収)

The Architecture of Written Japanese

11 Interchangeability

Chris Lowy

Last installment focused on the base text, and the installments before that on furigana. You will recall that the relationship between the two is a unilaterally dependent one: furigana cannot, without exception, exist without a base text to attach to; a base text, on the other hand, exists happily with or without furigana. However, this does not mean that the creation of text-world meaning vis-à-vis the visual representation of language is limited to the presence or non-presence of furigana. On the contrary: because the architecture of written Japanese makes use of at least three character sets (i.e., hiragana, katakana, and Sinographs), meaning can also be created by choosing (or not-choosing) how to visually represent language in the base text. The ability to switch between different character sets in the visual representation of otherwise identical language, and the meanings that are created by those choices, I call interchangeability. The notion of interchangeability, and the way meaning is created because of it, is the focus of this installment.

What is Interchangeability?

At its simplest, interchangeability as it relates to written Japanese is the principle that one can visually represent the same utterance in multiple ways. These differences in visual representation can be inconsequential or lead to the creation of a complete text-world, with the choice of a particular form of representation existing somewhere on the spectrum between conventionality and alienation. These feelings are not immutable: what the spectrum looks like depends largely on the period, context, and imagined reader.[1] Furthermore, and as previously discussed, since all Sinographs can be rewritten phonetically in either hiragana or katakana,[2] this condition of interchangeability is well established. Similarly, all hiragana utterances can be rewritten in katakana, and vice-versa. The reverse, however, from kana to Sinograph, is not always a realistic possibility. These orthographical choices, these aesthetic tweakings, can be of great importance to authors. The desire to continue tweaking is serious business: there is perhaps there is no better example than that of Natsume Soseki’s (1867-1916) Kokoro, a text situated squarely at the center of the modern Japanese literary canon. “Kokoro,” a complicated term, is explained by Meredith McKinney, the translator of the newest English edition, thus:

Kokoro, the novel’s title, is a complex and important word that can perhaps best be explained as “the thinking and feeling heart,” as distinguished from the workings of the pure intellect, devoid of human feeling. Because one’s kokoro thinks as well as feels, “heart” is at times an inadequate translation. Nevertheless, as the concept of kokoro is a pervasive motif throughout the novel, I have chosen to express it with the single word “heart” and to preserve its presence in the translation wherever possible. For the title, it seemed best to retain the original word.[3]

McKinney’s choice to keep the title untranslated is not novel. In fact, all four English translations have done this. The term is an important one, and central to understanding the psychological relationship between Sensei and his wife, Sensei’s dead friend K, and Sensei’s eventual suicide.

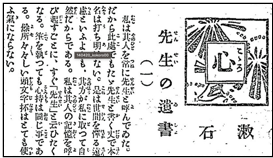

First serialized between April 20 and August 11 of 1914 in the Asahi Shimbun, Soseki’s serialization carried the title 「心 先生の遺書」 (Kokoro sensei no isho; Sensei’s Will and Testament). In this initial serialization, the Sinograph 心 appears with furigana (こゝろ; kokoro) attached to its right-hand side (Image 01).[4] The second character in こゝろ is a repetition marker indicating that the preceding kana ought to be repeated. For example, たゝかう would be read tatakau (“to fight”); similarly, すゞめ (“sparrow”) would be read suzume, with ゞ indicating that the preceding character (す) ought to be both repeated and voiced (ず). As an aside, the excerpt below is also an example of a sō ruby text: a text in which all Sinographs appear with furigana attached to them. (The only exception here is Soseki’s name.)

That original orthographical choice would not, however, last for long: just one month after serialization finished, Kokoro was published as a single-volume hardcover book – the first novel to be published by the Iwanami publishing house – with a new (?) title: こゝろ. That is, the furigana became the base text and the Sinograph 心 was dropped from the title. Confusingly, and as evidenced by Image 02, the slipcase to the hardcover book kept the initial Sinograph (心) while removing the furigana. To add further confusion, the current form of Kokoro, published by the same Iwanami, writes the title こころ, replacing the repetition marker ゝ with the appropriate hiragana (Image 03).

From the perspective of interchangeability, we see here that the word kokoro can be written as 心, こころ, or こゝろ. It is also the case that each of these visual representations can be rewritten as the other. So, what then do these changes signify?

What these changes signify, what they “mean,” varies widely and wildly depending on the text in question. In the context of Kokoro, the Sinographic orthography (心) suggests the larger Chinese philosophical and literary tradition that influenced so much of East Asia; it is also suggestive of Sensei’s world-view, one shaped more by Chinese (“Oriental”) thought than a Western one. A major theme of the text, of course, is the death of the Meiji Emperor in 1912 and the shadow it cast over a rapidly modernizing Japanese society, a change that would solidify the transition from one philosophical tradition to another.

Indeed, we know that the inside cover of the first printing of Kokoro included a page of various explications of 心, written in Literary Sinitic, and taken from the Kangxi Dictionary 康熙字典 (1716), the most authoritative dictionary of Sinographs through the early 20th-century (Image 04). The section cited includes quotes from a variety of ancient sources such as the philosopher Xunzi 荀子 (c. 310 BCE – c. 238 BCE) and the Shiming 釋名 (c. 200 CE), one of the oldest extant dictionaries of the Chinese language.[5] A clearer copy of the entry in question, taken from the 1978 reprint of the Kangxi Dictionary sitting on my bookshelf, gives us yet another visual representation of kokoro (Image 05)![6] This time 心 is annotated with different furigana, namely, コヽロ. For those keeping score at home, this is the fourth witnessed orthographical variation of the term kokoro, the first three of which appeared as official titles of the text. (There are five if we include the romanized spelling kokoro which serves as the title for every English translation!)

What I’ve discussed here are the basic facts relating to orthographical variation in the publication history of Natsume Soseki’s Kokoro, one of the most important pieces of modern Japanese fiction. You might think this conversation tedious or otherwise limited to the study of early modern literature. This question of variant orthographies in the visual representation of language – and, by extension, the creation of various text-worlds – is everywhere.

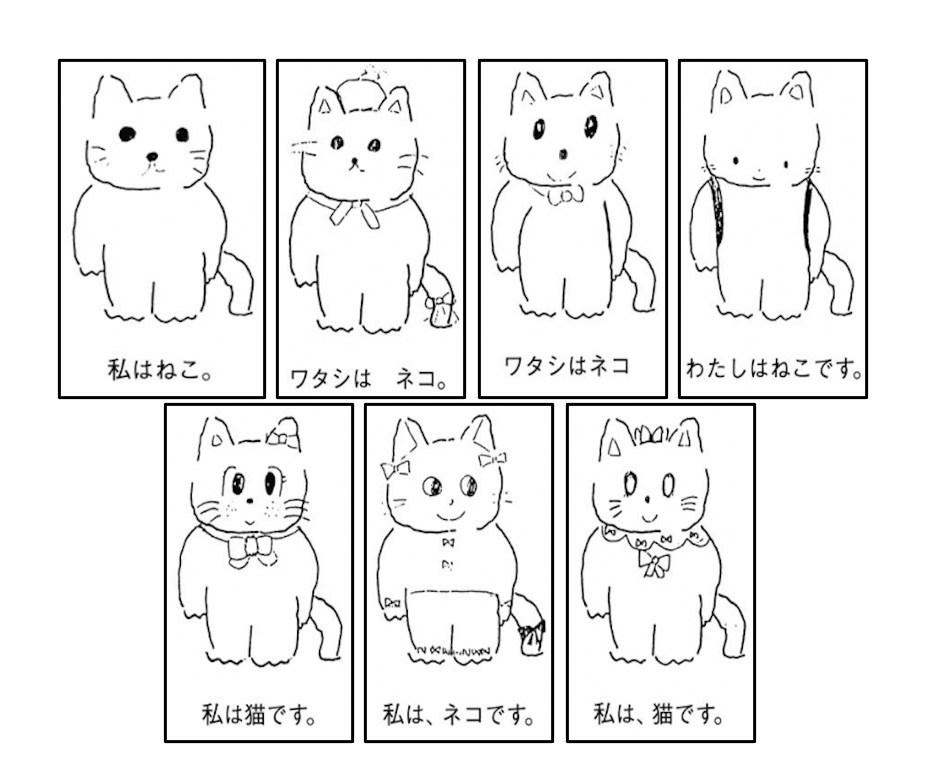

By way of Soseki, let’s look briefly at how literary scholar Komori Yōichi (1953-), himself a prolific critic of Soseki’s work, imagines the varied effects of orthographical variation – in other words, the effects of interchangeability – on a reader.[7] With the exception of the first three cats (which lack the copula desu), all lines in the images below are pronounced identically: watashi wa neko desu (Images 06-12).[8]

In a discussion of the numerous first person-pronouns used in Japanese – Komori references more than 10, many of them in jest – he provides illustrations of 31 cats, each depicting a different personality derived from a particular combination of first-person pronoun and base text. While Komori’s focus is largely on the meaning of multiple first-person pronouns in non-Western languages, especially in relation to structural linguist Émile Benvenist’s discussion of the first-person pronoun “I,” I am instead interested in the association Komori makes between the interchangeable visual representations of a single utterance (watashi wa neko [desu]) and each cat’s personality.[9] Seven base texts supplied by Komori are in Table 01.

| Base Text | Reading |

| 私はねこ。 | watashi wa neko |

| ワタシは ネコ。 | watashi wa neko |

| ワタシはネコ | watashi wa neko |

| わたしはねこです。 | watashi wa neko desu |

| 私は猫です。 | watashi wa neko desu |

| 私は、ネコです。 | watashi wa neko desu |

| 私は、猫です。 | watashi wa neko desu |

Watashi, the first-person pronoun, appears in three different forms (私・ワタシ・わたし), as does neko (ねこ・ネコ・猫). I will leave an analysis of the differences between each orthographic variant’s graphic representation to the reader, but it seems obvious that Komori, who has thought deeply about the Japanese language broadly and his own relationship to it specifically, instinctively understands the way written language shape’s a reader’s engagement with a text-world. Komori’s illustrations, presented tongue-in-cheek, resists theorization because there isn’t a larger context against which a critic can tease meaning from. For that, and for our final example, let’s turn briefly to a poem by Tanikawa Shuntarō.

“Non-Choosing” and the Creation of a Text-World

Tanikawa Shuntarō (1931-), perhaps the most well-known poet working in Japan today, published an anthology of poems in 1988 entitled Hadaka [Naked]. The first thing to note about the collection is the title itself: Hadaka appears not in Sinographs (裸) but in hiragana (はだか). In isolation, this isn’t necessarily noteworthy. Opening the collection, however, the reader notices that the more than 20 poems are all presented exclusively in hiragana. The question of intentionality now emerges, and we must ask ourselves: how does the decision to visually represent language in this way shape Tanikawa’s text-world? The poems, it turns out, are narrated by younger voices. They are simple but profound, unadorned by difficult vocabulary or by a complex orthography. Indeed, this mode of visual representation suggests an emotional nakedness and vulnerability; the simplicity of the written style leads the reader to take the words of the poet-narrator as truth. Below is “Kimi” (“You”), a typical poem from the collection.

きみはぼくのとなりでねむっている

しゃつがめくれておへそがみえている

ねむってるのではなくてしんでるのだったら

どんなにうれしいだろう

きみはもうじぶんのことしかかんがえていないめで

じっとぼくをみつめることもないし

ぼくのきらいなあべといっしょに

かわへおよぎにいくこともないのだ

きみがそばへくるときみのにおいがして

ぼくはむねがどきどきしてくる

ゆうべゆめのなかでぼくときみは

ふたりっきりでせんそうにいった

おかあさんのこともおとうさんのことも

がっこうのこともわすれていた

ふたりとももうしぬのだとおもった

しんだきみといつまでもいきようとおもった

きみとともだちになんかなりたくない

ぼくはただきみがすきなだけだ

you[11]

you’re sleeping next to me

your shirt is riding up and i can see your bellybutton

if you weren’t sleeping but actually dead

oh how happy i’d be

you’d stop staring at me with eyes

that only think about yourself

and there’d be no more trips to swim at the river

with that Abe i hate so much

when you come near me i smell you

and my chest begins to beat

in my dreams last night, me and you

just the two of us, went off to war

we forgot all about our moms and dads

and school

we both thought we’d both die

i want to, i thought, live forever with you who had died

i don’t want to be your friend, no

i simply love you

Taking the complicated topic of childhood love as its theme, the poem evokes the raw emotions experienced by the narrator and the feelings he directs at kimi, “you.” The visual representation of language allows the feelings of jealousy (“that Abe I hate so much”), nervousness (“my chest begins to beat”), contentment (“just the two of us”), and, finally, revelation (“i simply love you”) to float to the surface of the poem. Here, emotions take center stage. The poem, in fact, is a meditation on the pure love the male narrator feels for another boy, a love that will likely be pushed away or otherwise buried somewhere as he matures.[12] To be naked, then, is to be without the pressures of growing up, existing in a world of emotion. Hiragana, often considered a default character set, is used by Tanikawa to represent a move away from a visual adornment that, in his calculation, chains down and lessens the emotional power of the language. How this effect is achieved, however, is as much through Tanikawa’s rejection of both Sinographs and katakana as it is his choice of hiragana. By choosing to represent all language in hiragana he is resisting the reader’s imagined associations with Sinographs and, perhaps to a lesser extent, katakana.

In a sense, the world inhabited by Tanikawa’s poet-narrator is the antithesis of the one inhabited by Soseki’s Sensei in Kokoro: it may contain complex emotions, but the poet-narrator knows who he is and what he is feeling. The orthographical associations Tanikawa predicates his text-world on are not of his own invention. In fact, it is almost as if Tanikawa is writing in direct response to the ghost of another author: Tanizaki Jun’ichirō (1886-1965). As early as 1917, Tanizaki was lauding the visual aesthetics of Sinographs and their effects on a text-world. “For poets,” he says,

characters truly are jewels. As in jewels, there is sparkle in characters, and hue, and scent. The radiance of the diamond, the gracefulness of the turquoise, the mysteriousness of the alexandrite, the sweet loveliness of the ruby, the vitality of the aquamarine, seek and you will find such qualities within characters.”[13]

Published 17 years before Bunshō tokuhon (A Composition Reader), Tanizaki’s extended treatise on the role of written language in Japanese-language literature, this essay is a defense of Sinographs and their use in literature at a time when passionate calls for language reform where everywhere. He argues that Sinographs “are indeed the most sensual” of all characters, and removing them from the written form of Japanese “would be much like discarding a jewel and settling for rubble.”[14] The use of a single character set, on the other hand, alleviates the need to consider visual cadence in poetry, an ostensibly oral form of literary expression, and focus instead on the narrative message. By removing the element of visual variation from the poetic space, Tanikawa refocuses the attention of the reader onto the (naked) words themselves. This nakedness, it must not be forgotten, is hardly naked: it only feels that way because it is neither Sinographs nor katakana.

Conclusion

Tanikawa’s text-world stands atop the principle of interchangeability. If the architecture of written Japanese did not allow for the use of multiple character sets, then the effect of choosing (or not-choosing) one set would minimal. And these small choices pop-up everywhere, from Soseki’s form of visually representing the term kokoro to the way Komori Yōichi chooses to represent 31 cats, some of whom possess different personalities based not on their first-person pronoun but on the way they (he) choose(s) to visually represent a single utterance. Komori’s experiment, however, stops there: as I’ve argued earlier in this series, it is generally not possible to say what an orthographical choice “means” without narrative content to contextualize it. Tanikawa’s poetry allows us to do this. If it is Tanikawa’s goal to strip written language of its visual baggage, then how should we think about literary fiction that regularly incorporates textual visuality into its texts? That will be the subject of the next installment and the final element of the architecture of written Japanese: the principle of an “open” set of Sinographs.

[1] For example, a text written all or largely in hiragana would be received differently when read in a premodern or modern context. The reasons for this are varied – education, audience, the use of variant kana (変体仮名) and the historical orthography (歴史的仮名遣い) that aid in disambiguating terms, etc. – but my focus here is on the actual visual representation of language.

[2] There is a more nuanced discussion to be had on this topic. All Sinograph and Sinograph character-strings have, in theory, an associated reading, a way to verbalize the language represented by the Sinograph or Sinograph combination. These readings are what can be written in both hiragana or katakana.

[3] See “About the Title” in Natsume Soseki, Kokoro, trans. Meredith McKinney, Penguin Books, 2010.

[4] I have borrowed this image from literary scholar Itō Tetsuya’s personal blog Tatsumi no iori yori. The blog post in question, from April 20,2014, provides commentary on the differences between various published forms of Kokoro. The occasion for this blog post was the 100th anniversary of the commencement of Kokoro’s initial serialization.

[5] A digital copy of the 1914 printing of Kokoro can be freely accessed from the National Diet Library Digital Collection here.

[6] Kōki jiten [Kanxi dictionary], Kodansha (1978): 859.

[7] As is well known, Komori, together with Ishihara Chiaki, helped initiate the important and controversial “Kokoro debates” of the mid-1980s. As another scholar has put it, “rebels showed up at the main gate to the palace [of traditional modern Japanese literary studies], battering ram in hand.” For an extended discussion of these debates, and Komori’s role in them, see Bourdaghs, Michael K., “Overthrowing the Emperor in Japanese Literary Studies” in The Linguistic Turn in Contemporary Japanese Literary Studies, University of Michigan Press (2010): 1-17.

[8] Komori Yōichi, Komori Yōichi – Nihongo ni deau, Taishūkan shoten (2000) :167-9. Thanks to Kurihara Yutaka for first telling me about this text so many years ago.

[9] There is one glaring omission missing from this set of 31 illustrations: wagahai wa neko de aru [I am a Cat], the title of another important book by Soseki and published between 1905-6.

[10] Shuntarō Tanikawa. Hadaka: Tanikawa Shuntarō shishū (Chikuma shobō, 1988): 35-7.

[11] This translation is my own. For another English rendition see William I. Elliot and Kazuo Kawamura, Naked: Poems by Shuntaro Tanikawa (IBC Publishing, 2006): 18-9.

[12] Tanikawa himself acknowledges the “gayness” of the poem. Speaking about “Kimi” while engaging in a wide-ranging dialogue with Yamada Kaoru, he describes the poem as “absolutely gay” (kanzen ni gei desu), saying he himself had “gay tendencies while in middle school” (chūgakusei no koro ni gei no keikō ga atta kara), Tanikawa Shuntarō and Yamada Kaoru, Boku wa kō yatte shi o kaitekita: shi to jinsei o kataru 1947-2009, Nanaroku-sha (2010): 402. I would like to thank Yoshihiro Yasuhara, my colleague, for sharing this source with me over drinks one night. Thank you for allowing me to confirm my reading!

[13] Thomas LaMarre, “Poetry and Characters,” in Shadows on the Screen: Tanizaki Jun’ichiro on Cinema & “Oriental” Aesthetics, University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies, 2005: 26. The original, taken from “Shi to moji to,” reads: 詩人に取りて、文字はまことに寶玉なり。寶玉に光あるが如く、文字にも亦光あり、色あり、匂あり。金剛石の燦爛たる、土耳古石の艶麗なる、アレキサンドリアの不思議なる、ルビーの愛らしき、アクアマリンの清々しき、──此れを文字の内に索めて獲ざることなし,” Tanizaki Jun’ichirō zenshū vol. 14, Chūō kōron sha (1959): 62.

[14] LaMarre, 26.