今野真二

第7回では振仮名を言語事象として採りあげた。「語」を単位として考えた場合、漢字列に施されている振仮名は、ひろく漢字列についての「注釈」とみることができる。ただし、「書き手」と「読み手」とでは「注釈」が意味するところが異なる。

漢字列「荷葉」に「はすのは」と振仮名が施されている場合を例にして説明する。「書き手」は何らかの「文」をつくろうとしていて、その「文」を構成する「語」として「ハスノハ」という語(注1)を選択した。そしてその「ハスノハ」を「文字化」するにあたって、「蓮の葉」ではなく、漢字列「荷葉」を使うことにした。振仮名についてはまず「書き手」の立場からこのように考えたい。この場合振仮名「はすのは」は「書き手」が選択した「語」(の発音)を示していることになる。「はすのは」が「語」をあらわしているのか、「語の発音」をあらわしているのか、ということについては「語」とは何かということと関わって、丁寧に考えておく必要があるが、現時点ではそのことについて論じるだけの準備が稿者にできていないので、今ここではその点についてはふみこまない。

一方、「読み手」は漢字列「荷葉」に「はすのは」と振仮名が施されているのをみれば、「書き手」が漢字列「荷葉」を「はすのは」と読ませようとしている、あるいは漢字列「荷葉」の「よみ」が振仮名によって示されているととらえやすい。このように、振仮名については、事象の外側にいる観察者・分析者は、「書き手」にとって振仮名をどう定位すればよいかということと「読み手」が振仮名をどうとらえるか、とらえやすいかということの双方についての目配りが必要になる。「振仮名」という1つの言語現象に関して、「書き手」と「読み手」に目配りが必要なことについて観察者・分析者はつねに留意しなければならない。

「書き手」は自身が選択した語がいかなる語であったかを振仮名で示し、「読み手」は振仮名によって漢字列がいかなる語を文字化したものであるかを知る。そう考えた場合、振仮名は「書き手」「読み手」双方にとって「注釈」機能をもっているみることができる。

振仮名が施されている漢字列を使って「文」をつくり、そうした「文」が集まって「文章」をつくり、あるまとまりをもった「テキスト」をつくる。振仮名が使われている「文・文章・テキスト」は注釈付きの「文・文章・テキスト」とみることができる。

以後では、「テキスト」を観察の単位として述べていくことにする。

現代日本語によって成っているテキストは振仮名をあまり使わない。しかしそれでも振仮名を使ったテキストは少なからず存在している。振仮名を使ったテキストを一方に置いた時、つまりそういうテキストが存在できることを認めた時に、そうしたテキストから「振仮名を除いたテキスト」が想定できることになる。言い換えれば、「注釈」が施されていないplainなテキストを想定することができる。そもそも、「注釈」を施したテキストが存在しないのであれば、「plainなテキスト」という概念が成り立たない。日本語の場合、振仮名を初めとして「注釈」を施したテキストは過去においても現在においても存在しているので、plainなテキストが想定できる。その「plainなテキスト」を「Base Text」と呼ぶことにして、今回はその「Base Text」について考えてみたい。

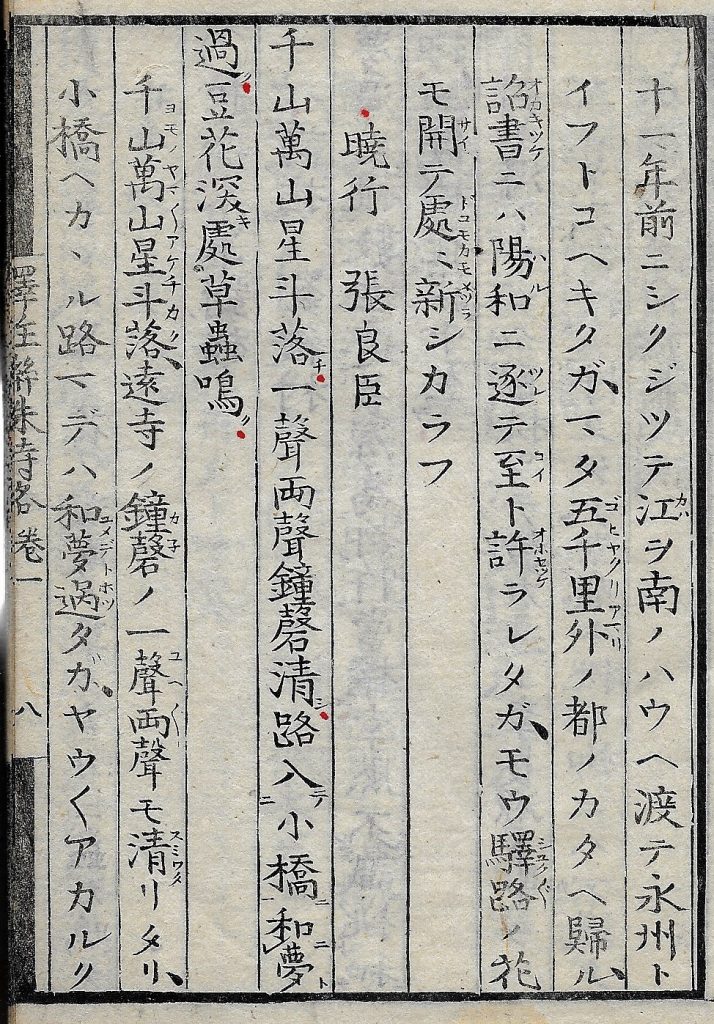

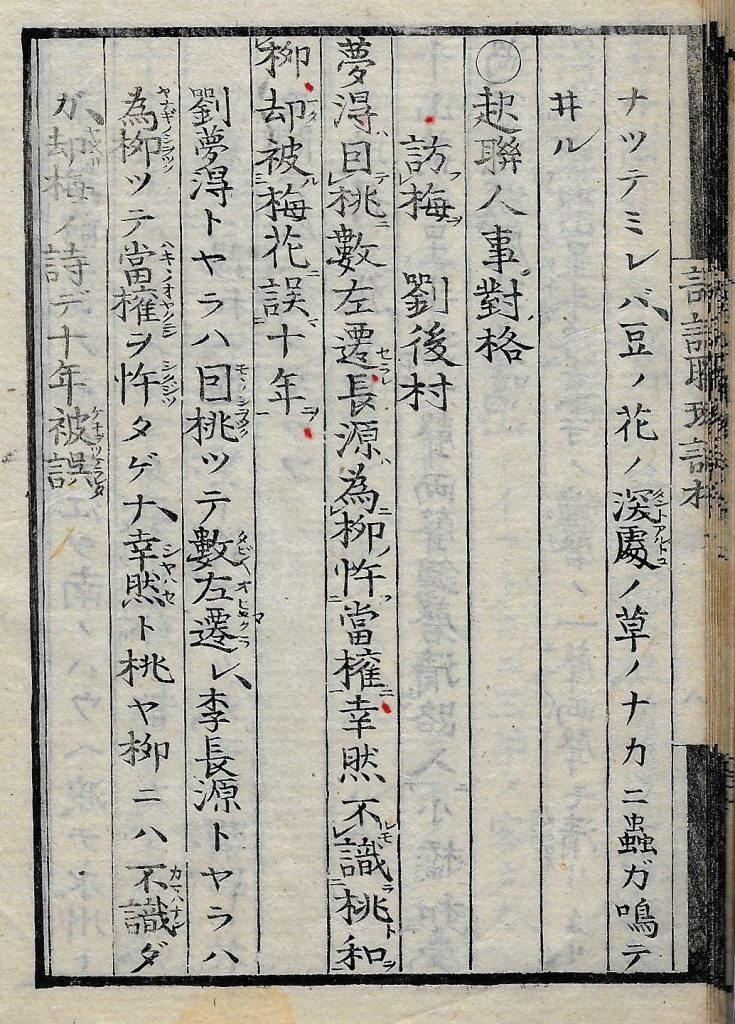

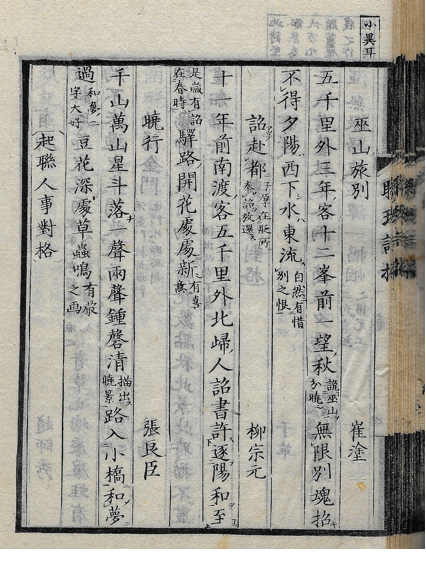

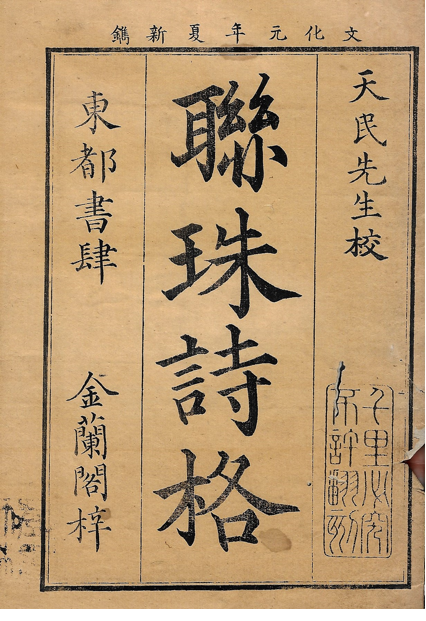

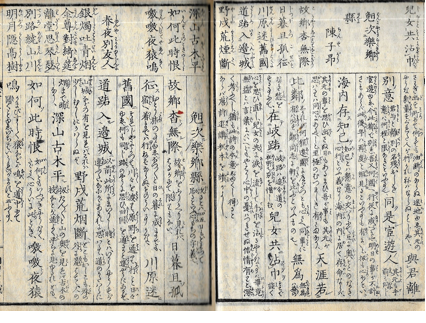

図1・2は江戸時代後期の詩人柏木如亭(1763-1819)が、中国、宋末・元初の于済(うせい)が原撰し、同じ宋末・元初の蔡正孫(さいせいそん)が増訂・附注して20巻本として元の大徳4(1300)年に刊行したアンソロジー『聯珠詩格(れんじゅしかく)』を抄訳し、享和元(1801)年に4巻2冊(乾・坤)のしたてで出版した『譯注聯珠詩格』(注2)の乾巻の8丁の表・裏の箇所である。図3は文化元(1804)年に山本北山の序を附して、日本において20巻5冊のしたてで出版された『唐宋聯珠詩格』の巻1の4丁裏。

山本北山(1752-1812)は江戸時代の儒学者で、安永8(1779)年に『作文志●(さくぶんしこう)』(●は彀、穀の木を弓に換えた字)、天明3(1783)年に『作詩志●』を刊行して、当時勢力があった古文辞学派の擬古主義を批判した。享和4(1804)年には漢文体の笑話集『笑堂福聚』を出版している。山本北山は、古文辞学派が重視する『唐詩選』が偽書であることを述べ、その一方で明の袁宏道らの「公安派」を理想として、宋詩を重んじた。江戸時代の「知」を考えるにあたっては、宋詩をどのように評価するかが1つの基準となると考える。

図4は『唐宋聯珠詩格』の表紙見返し。表紙見返しには「天民先生校」とあるが、「天民」は山本北山の門人であった大窪詩仏(1767-1837)の字(あざな)。大窪詩仏は市川寛斎、柏木如亭、菊池五山とともに江戸の4詩家と呼ばれることがあった。大窪詩仏の詩作品には、中国、南宋の3大家、范成大、楊万里、陸游の詩の影響が指摘されている。

図3は訓点(送り仮名)が施されていることからわかるように、日本において出版された『唐宋聯珠詩格』であり、中国において出版されたテキストではない。したがって、厳密な意味合いでは『唐宋聯珠詩格』の「Base Text」ではない。しかし、そうしたことを別にすれば、ほぼ『唐宋聯珠詩格』の「Base Text」といってよいだろう。それに対して、図1・2すなわち『譯注聯珠詩格』は注釈が施されたテキストにあたる。

中国でつくられたテキストが日本に輸入され、その中国のテキストをもとにして、日本によって印刷が行なわれることは江戸時代においては珍しいことではなかった。そのようにしてつくられた日本製テキストを「和刻本(わこくぼん)」と呼ぶ。「和刻本」の多くは訓点(振仮名・送り仮名・返り点)が施される。訓点は「Base Text」としての中国のテキストをどのように日本語として理解すればよいか、どのように日本語に翻訳するかを示しているとみることができ、「注釈」といってよい。

『譯注聯珠詩格』は「Base Text」である『唐宋聯珠詩格』の巻1-4に収められている七言絶句199首から128首を選び、訳注を加えたテキストで、「Base Text」をもとにして積極的な意図をもってつくられた新たなテキストとみることができる。

図1は南宋の詩人、張良臣の「暁行(ぎょうこう)」というタイトルの詩であるが、原詩と注2に示した岩波文庫の「読み下し」を次に示す。

[原詩]

千山万山星斗落

一声両声鐘磬清

路入小橋和夢過

豆花深処草虫鳴

千山万山 星斗(せいと)落ち

一聲両聲 鐘磬(しょうけい)清し

路は小橋に入りて夢と和(とも)に過ぐ

豆花(とうか)深き処 草虫(そうちゅう)鳴く

柏木如亭は次のように「訳注」を行なっている。繰返し符号は「々々」で置き換えた。

千山万山星斗落(ヨモノヤマ々々アケチカク)

遠寺ノ鐘磬(カネ)ノ一聲両聲(コヘ々々)モ清(スミワタ)リタリ、

小橋ヘカヽル路マデハ和夢過(ユメデトホツ)タガ

ヤウ々々アカルクナツテミレバ、

豆ノ花ノ深処(タントアルトコ)ノ草ノナカニ虫ガ鳴テヰル

漢字列「千山万山星斗落」に施されている振仮名「ヨモノヤマ々々アケチカク」は漢字列があらわしている中国語全体を七拍五拍、すなわち七五調の日本語に翻訳しており、語を単位として施されている振仮名とは異なる機能をもっているといってよい。

「遠寺」は「Base Text」にはない語で、如亭が原詩の理解、翻訳のために補っている。また、「ヤウ々々アカルクナツテミレバ」も原詩にはないが、すべて片仮名で文字化することによって、原詩にはないことをあらわしていると思われる。

現在は、「漢字平仮名交じり」を標準的な「表記体」とし、外来語や動植物名、場合によってはオノマトペなどに片仮名を使うことが多いので、かえって文字種に対しての「読み手」の意識が希薄になっているかもしれないが、江戸時代においては、漢字・平仮名・片仮名が1つの文章、1つのテキストの中で混ぜ用いられることは多くはなかった。

「原詩」は七言絶句であるので、漢字が28使われているが、「訳注」には、「原詩」第3句(転句)の「入」字が使われておらず、さらに、第2句(承句)に「遠寺」の2字が加えられているので、「訳注」には漢字29字が使われている。少しの出入りはあるが、ほぼ「原詩」に使われている漢字が「訳注」にも使われていて、そうした意味合いにおいて「Base Text」が意識され、踏襲されているといってよいだろう。

本居宣長は『古今和歌集』を口語、すなわち江戸時代の「はなしことば」に訳した『古今集遠鏡』をあらわしているが、漢詩文に関しては、荻生徂徠が漢詩文を文語によって訓読するのではなく、中国語音で直読し、日常的なことばによる「訳」を行なうべきことを主張し、(おそらくはそうしたことがきっかけとなって)江戸時代には漢詩文の俗語訳が行なわれることがあった。正徳5(1715)年には森川許六の『和訓三体詩』が出版され、宝暦13(1763)年には徂徠が明詩の絶句を注釈した『絶句解』を俗語解した中川南峯の『絶句解弁書』が、安永3(1774)年には六朝の五言絶句300首ほどの俗語訳である田中江南の『六朝詩選俗訓』が出版されている。

如亭の「訳注」は原詩の「訳注」であることにとどまらず、1つの作品としてよむことができる。そうであれば、于済が撰び、蔡正孫が大徳4(1300)年に出版した『唐宋聯珠詩格』は時空を超えて如亭によって新たなテキストをうみだしたことになる。文学作品における「翻案」「パロディ」は「Base Text」からの「スピンオフ」といえるだろうし、もともとの「書き手」も含めて「リメイク」(注3)も「Base Text」からの新たな表現といえる。

いささか話が大きくなりすぎることを承知でいうならば、日本文化、日本語にとっては中国文化、中国語が「Base Text」であった時期が長く続いたといってもよいだろう。中国語が借用され、日本語の語彙体系内に位置を占めたと言われることがある。「位置を占めた」は場所を得て、静的(static)にそこにあることを思わせるが、漢語が日本語の語彙体系内に位置を占めるためには、当然、すでにある和語との「交渉」が必要になる。「交渉」は和語によって漢語を探ることであり、動的(dynamic)なactionといってよい。1つの漢語が位置を占めるまでにどれだけの動的なactionが行なわれるか。あるいは次々に漢語が「交渉」を行なっている時期には、日本語の語彙体系(のある部分)がつねに揺さぶられているような状態になる。テキストにおいて漢語が使われることによって、現代の観察者は漢語が使われたことを認識する。それは海彼から来た渡り鳥が日本の湖沼に降り立っているのを見て、渡り鳥の渡来を確認するようなものであるが、渡り鳥がそこに降り立つまでにはいろいろな事があったはずで、それを想起することによって、「わたり」のdynamismをあれこれと想像することも時には必要であろう。

上に述べた「動的なaction」は漢語が定着するにあたっての「動的なaction」であるが、それが和語をも動かすことがないとはいえない。2つの和語の間に漢語が1つ入るのであれば、2つの和語は少し位置を変えるだろう。平安時代、鎌倉時代、室町時代、江戸時代、それぞれの時代に、中国と日本との深い接触があった。その深い接触にともなって、中国文化、中国語が日本語の中に入ってきたとみるならば、日本語はずっと動的な「動的日本語」であったことになる。「Base Text」という概念を設定することで、日本語の歴史のとらえかたが変わるというと強弁だろうか。「動的な日本語の歴史」あるいは「日本語の歴史を動的にみる」という意味合いでの「新しい日本語の歴史」記述の試みは1度はしてみる価値があると考える。

図5は『唐詩選和訓』(注4)再版本第1冊「五言律」の2丁裏-3丁表の箇所。陳子昂の「晩次楽郷県」(晩(くれ)に楽郷県に次(やど)る)という作品を話題にする。版本の匡格内は縦がおよそ20センチメートルで、その4分の1ほどが区切られている。ここを「上部欄外」と呼ぶことにする。その上部欄外には詩作品=原詩が掲げられている。ただし、訓点を附した上で、詩の「よみ」が振仮名として施されている。一方、「上部欄外」の下部には詩が、句を単位として、片仮名で訓点を附して掲げられ、それに続いて、「本文」よりも小さな字で2行に割った「細字双行」で「注解」が施されている。

もともとの詩作品は紛れもない「Base Text」といえよう。それを書き下すにあたっては、「漢字片仮名交じり」の表記体が選択されることが一般的であろう。そう考えると、上部欄外の振仮名が平仮名であることは、このテキスト全体が「日本側」にあることを思わせる。その一方で、「本文」の漢詩句の送り仮名が片仮名であることは、「本文」として掲げられている詩が「Base Text」にちかいものと認識されていることを推測させる。

例えば「日暮且孤征」であれば「注釈」は「ひとり旅の事ゆゑ、ぼつ々々と日の暮に成までも、宿へ着までは行ねばならぬ、ものうい事かな、」のような日本語で「注釈」されている。『唐詩選和訓』冒頭には「唐詩選和訓序」が置かれているが、そこには「今此書は鄙言俚語(ひけんりご)にて詩のあらましを解(げ)するなり」とある。「鄙言俚語」を「はなしことば」ととらえるならば、「細字双行」となっている部分はよりいっそう「日本側・日本語側」にあることになる。「川原迷舊國」の「舊國」は「細字双行」においては「旧国(きうこく)」となっており、また「野戍荒烟斷」の「斷」は「細字双行」においては「断」が使われている。

「舊」「國」「斷」は『康熙字典』が見出しとして掲げる「康熙字典体」にあたる。一方、「旧」「国」は『康熙字典』が見出しとして掲げていない「非康熙字典体」にあたり、「断」は『康熙字典』が「俗字」として扱っていると思われる字にあたる。『康熙字典』が掲げている字が日本の江戸時代においてもformality がたかいということは証明はされていないと考えるし、formalityを何をもって測定するかということも吟味されていないと思われる。したがって、ここでは単に『康熙字典』が見出しとする字かどうかということをscaleとするが、そのscaleを使うならば、「細字双行」内では『康熙字典』が見出しとしていない字形(注5)が使われることがあるということはできるだろう。

「Base Text」という概念を設けることが、日本語の観察、特にテキストを単位とした日本語の観察にやくだつことは疑いがない。

注1 「ハスノハ」は1語であるか、言語における「語」とは何かということを議論する必要はあり、そのことは日本語表記と深くかかわると考えるが、今ここでは「ハスノハ」を1語とみることにする。また鉤括弧に片仮名を入れた場合、どのように文字化されているかということを離れて「語」そのものをあらわしている。

注2 『譯注聯珠詩格』は『訳注聯珠詩格』(2008年、岩波文庫)によってよむことができる。

注3 今野真二『リメイクの日本文学史』(2016年、平凡社新書)は「リメイク」について、言語に密着して具体的に述べている。

注4 『唐詩選和訓』には寛政2(1790)年、寛政5年に出版された初版(全3冊)と文政6(1823)年に出版された再版(全4冊)とがある。寛政2年には「五言絶句」と「七言絶句」と合計2冊が、寛政5年には「七言絶句」の「続」篇1冊が出版されている。文政6年には「五言律詩」「五言絶句」が各1冊、「七言絶句」が2冊、合計4冊のしたてで出版されている。図5は稿者が所持している再版本の画像。山本佐和子は「嵩山房刊『唐詩選和訓(とうしせんききがき)』五言絶句編(上)」(『同志社国文学』90号)において、「再版本は覆刻ではなく、初版本と全体の構成・頁の配置まで類似して本文もほぼ同文だが、仮名字体や仮名遣、一部の漢字表記が異なる。総ルビに近い詩解の振り仮名として示される語が違う例もある。漢詩に付される訓点も、捨て仮名の使用は初版のみであるなど、若干の違いがある。再版本第一冊「五言律詩」の内容や言語面の初版三冊との差も鑑みると、書肆側の意図の変化を考慮すべきだが、両版の差が寛政期~文政期の言語変化に因る例もあるだろう」と述べている。したがって、画像に基づいて本稿が述べたことは、あくまでも再版の版面において指摘できることがらということになる。「早稲田大学図書館古典席総合データベース」において4冊のうちの2・3・4合計3冊の画像が公開されている坪内逍遙旧蔵本は文政6年版(再版)。

注5 今ここでは「字体」「字形」について定義をしないで、単に字の形という意味合いで「字形」と表現しておくことにする。

The Architecture of Written Japanese

10 The Base Text

Chris Lowy

The past three installments of this series introduced the concept of furigana, its use in contemporary fiction, and the various ways authors mobilize furigana to achieve a myriad of desired results. The existence of furigana is, perhaps, the most interesting characteristic of written Japanese. Recall that, despite its name – literally, assigned or allotted kana – furigana can be in any script and can be applied to any base text. Furthermore, if the reader will indulge me some, the very possibility of attaching furigana to a base text creates a situation in which there are always some (invisible) reading(s) behind all unannotated text. This space of possibility wherein expression is born, the base text, is the focus of this installment.

The Ubiquity of the Base Text

I have so far explored the following characteristics of what I call the architecture of written Japanese: the continuous use of three character sets, the presence of typographic markers adapted from both Chinese and Western sources, bidirectionality in right-originating vertical writing and left-originating horizontal writing, ubiquitous and predictable space distribution, and furigana. The text that exists regardless of the presence of furigana – but for whom furigana’s existence is contingent upon – is called the base text, the next characteristic of written Japanese.

In most cases, the base text alone is sufficient for the successful communication of ideas. Even if one cannot “correctly” read a character or character-string – “correct” here referring to its reading and not its denotative meaning – it should, in theory, be comprehensible.[1] The base text as it appears before a reader is static: it is a snapshot of the visual representation of language, a fossilized relic of an author’s (or editor’s) script practice that are in turn presented to a reader. I am being careful with my words here for the simple reason that a base text can change when it’s reading and denotative meaning do not. For example, the famous opening lines of Natsume Soseki’s I Am a Cat (1905), “Wagahai wa neko de aru. Na wa mada nai.” (“I am a cat. As yet I have no name”), regularly appears in two variant base texts.[2]

吾輩は猫である。名前はまだ無い。

吾輩は猫である。名前はまだ無い。

The difference here, namely, the presence or absence of furigana on the character-string 吾輩, is unremarkable. Inconsequential though it may seem, the phenomenon these differences suggest – that different base texts can only be identified through visual access to the text – is significant. In certain contexts, those differences can, and do, shape meaning. Consider the following ten sentences.

(i)あれはきのこです。

(ii)あれはキノコです。

(iii)あれは茸です。

(iv)あれは菌です。

(v)あれは蕈です。

(vi)アレはきのこです。

(vii)アレはキノコです。

(viii)アレは茸です。

(ix)アレは菌です。

(x)アレは蕈です。

For the sake of argument let’s assume that each sentence is meant to be read are wa kinoko desu (“that [over there] is a mushroom”). We now have ten examples of the same utterance represented with ten different base texts. Some are more common than others (i, ii) while others stand out due to their visual representation of both the demonstrative are and the word for mushroom, kinoko (viii-x). Nevertheless, each of these base texts are possible and, within an established environment (what we might call a particular author’s text-world), potentially mundane. The point here is that each of these base texts represent an authorial choice: remember, within the architecture of written Japanese a conventional mode of visual representation is still a choice. This question of choice and the base text, for example, figures prominently in the work of author Sakiyama Tami. In Sakiyama’s 2014 short story “Q-Village Front Lines b,” the following words appear in katakana in the base text without further annotation: オトコ (otoko; man), モノ (mono; thing), ヒトビト (hitobito; people), ムラ (mura; village), ケイカク(keikaku; plan), クンレン (kunren; training), ムラビト (murabito; village people), ヒト(hito; people), アンタ (anta; you), テキ (teki; enemy), ボク(boku; I), ジッタイ(jittai; substance), and コトバ (kotoba, language).[3] Each of these words are typically written in Sinographs or hiragana.

I see hands in the air, largely from the literary scholars in the back of the room. “Okay, fine, but what, if anything, do these choices mean,” you ask. Don’t worry, we’ll get to that. Strategies for deriving meaning from these little choices will be the topic of an entire installment. For now, though, we consider the significance of the co-dependent relationship between the base text and furigana.

The Limits of the Base Text

I see another hand in the back – yes, you are indeed correct. The Latin script, too, has a base text. In fact, all written languages must have a base text. Without it there would be nothing to read. The critical difference between the base text of written Japanese and that of English is that the former is regularly subjected to annotation while the latter is not. This is one reason that texts written in the Latin script are expected to adhere to normative orthographical standards. Put another way, the architecture of written Japanese is tolerant of variation because the constant possibility of annotation blurs the line between correct and incorrect while the lack of annotation in written English enables the establishment of fixed orthographical rules dictating a (base) texts’ correctness.[4] If the architecture of a script does not allow for standardized variation, it seems reasonable that authors would not look to that script to create visual representation. [5] This does not, however, mean that some authors have not tried to incorporate visual elements into their representation of written language.

For example, consider the opening poem by E. E. Cummings in his classic 95 Poems (1958).

l(a

le

af

fa

ll

s)

one

l

iness

The poem initially confuses the reader. At first glance one is tempted to return the book to its place on the shelf (or, as is more likely today, to return to the home screen of an eBook reader). But the ice of confusion begins to melt: we first identify “one” before our eyes jump to “iness” – aha!, with that hanging “l” we understand “oneliness.” Back at the beginning and the initial “l” – for a second, we wonder if it is to be read as “one” – comes into play: we now have “loneliness.” We return to the parentheses and what they contain, and it all makes sense: l(a leaf falls)oneliness. The lack of space between the letters and parentheses suggests something other than a parenthetical; it creates simultaneity. The occurrence of this single leaf falling does not cause loneliness but, instead, occurs while one is in the throes of it. There is also motion. The simultaneity of these two states does not mean the two occurrences are of the same duration. Rather, the initial snap and ensuing downward twirl of the leaf is contained within the sensation of the poet-subject’s loneliness. We don’t know if the subject is watching this embodiment of their melancholy, but we do know that this fallen leaf-loneliness has reached the ground. By the end of the poem the two images have fused together. Mitchell Morse, quoted in Richard S. Kennedy’s reevaluation of Cummings’s work, argues that this poem is a “compact visio-literary experience” that carries the “spirit” of a haiku.[6] I’m not qualified to evaluate the absence or presence of a haiku “spirit,” but the successful juxtaposition of two images – a “compact visio-literary experience” – is noteworthy.

I dwell here on Cummings’ poem to demonstrate that while, yes, the visual representation of language in an alphabetic script environment is possible it is not easily achieved. The way Cummings creates this “compact visio-literary” moment of leaf-loneliness is not easily reproducible. Rather, it is only by jamming an entire phrase (“a leaf falls”) inside a word (“loneliness”) that the two images can fuse (and confuse). Cummings must resort to such extreme measures because he has only a base text to work with. As I argue throughout this essay series, those who wish to push a written language to its limits must do so within the architecture of the script(s) they write in.

On the other hand, within the architecture of written Japanese the possibility for combining two words or phrases in a way reminiscent of Cummings can be easily achieved by attaching furigana to the base text. This gives an author two ways to reproduce Cummings’ experiment. For example, one might combine “a leaf falls” (hitoha otsuru) with “loneliness” (sabishisa) in the same way Cummings does.[7]

さ(ひ

と

は

お

つ

る)

びしさ

The result, さ(ひとはおつる)びしさ, or sa(hitoha otsuru)bishisa, recreates the imposition of a phrase (hitoha otsuru) into the middle of a word (sabishisa). This would be as irregular in written Japanese as it is in English.

Another, more mundane option, is to place one image on top of another. Since the phrase “a leaf falls” appears inside “loneliness” I will take the latter as the primary utterance and thus as the base text.

さびしさ

The two images become one (visual) moment. Alternatively, an author might choose to use (any number of) Sinographs in the base text.

寂しさ

淋しさ

Using Konno’s term, this is an example of furigana-as-expression (hyо̄gen toshite no furigana). Furigana-as-expression, a phenomenon related to the “visio-literary” moment Morse detects in Cummings’ poem, is everywhere in literature written in the Japanese script. An interesting illustration of such a moment, chosen at random, is from the Japanese translation by Kuroma Hisaishi of William Gibson’s classic piece of science fiction, Neuromancer (1984).

Cath rocked back on her tanned heels and licked at a strand of brownish hair that had pasted itself beside her mouth. “What’s your taste?”

“No coke, no amphetamines, but up, gotta be up.” And so much for that, [Case] thought glumly, holding his smile for her.

“Betaphenethylamine,” she said. “No sweat, but it’s on your chip.”[8]キャスは日灼けした踵に体重を移して、口の脇に張りついた茶色っぽい髪を一筋ねぶり、

「お好みは・・・・・・」

「コカインは駄目、アンフェタミンも駄目、とにかく刺激的に、覚醒的で」

言ってみればそういうところで、とふさぎこみながらも、ケイスは相手には笑顔を向ける。

「ベータヘニチルアミンね」

とキャスは言い、

「簡単よ。ただし、お代はあんたの素子にかかるけど。」[9]

Betaphenethylamine, or Beta for short, is a powerful stimulant. And for Case, who altered his body to no longer metabolize cocaine or amphetamines in an attempt to curb his drug addiction, it was the only option left for chemical stimulation. This short passage alone contains four examples of visio-literary moments, though I will only discuss the most interesting: two common character-strings – 刺激的 (shigekiteki; stimulating, provocative) and 覚醒的 (kakuseiteki; stimulating, arousing) – are both assigned the same appu reading. The (katakana spelling of the) English word “up” and, indeed, all the furigana in this section, indicate Kuroma’s desired word-form. That is, the relationship between appu (which most readers of Japanese would associate with the English word “up”) and its meaning of “getting high” is tenuous within a Japanese language environment. Nevertheless, Kuroma insists on establishing this association, succeeding in doing so by fusing the two images together with furigana. This particular “visio-literary” moment is not ancillary to the text; it is the text. Put another way, Kuroma’s translation strategy is to rely neither on the base text or the furigana. It is the combined moment that creates meaning, meaning created in the dialogue between the base text and the furigana attached to it.

Why Possibilities Matter

Thinking in terms of binary oppositions is not as fashionable as it once was. Nevertheless, the significance of the base text changes within an architecture of script that has normalized interlinear glossings, i.e., furigana, and one that does not. In a script system that lacks furigana, we can say that the base text exists opposite of its absence: there is either text or there isn’t. While this is also true in a script system that does have furigana, it is also true that the base text exists opposite to its glossings. In other words, a base text is a base text because it isn’t furigana; conversely, furigana is furigana if it resides above the base text. Understanding this absolute relationship between the base text and the capability for annotation will allow us to consider the final two characteristics of the Japanese writing system: interchangeability and an expansive (or “open”) set of Sinograph and Sinograph-like characters. Interchangeability, which is the ability to write the same utterance in a variety of word-forms, is the topic on the next installment.

[1] Such acts of misreading are, of course, not limited to Japanese. For example, I care not to disclose the age at which I began correctly pronouncing “epitome.” Despite my misreading, in my mind both eh-pih-tome and uh-pih-toe-me meant “the best example of [x].”

[2] I’ve borrowed Mōri Yasotarō’s translation of the opening lines.

[3] “Q-Village Front Lines b” (Q mura sensen b) were first published in the literary journal Subaru (2015) and is contained in Unjuga, nasaki, Hanashoin, 2016.

[4] The establishment of a fixed orthography was not an inevitable outcome of the architecture of the Latin script. On the contrary: the goal of establishing a fixed orthography, an important step in the creation of a standard written English, was achievable within the architecture of the Latin script by creating fixed spellings. The desire for standardization was shaped by the capabilities of the Latin script. Conversely, the architecture of the Japanese script would mold notions of standardization into different shapes.

[5] I am speaking in generalities here. There will always be examples of authors pushing back against standard orthographical practices and what it represents. Ezra Pounds’ The Cantos is printed in an often erratic style while (in)famously containing Sinographs throughout the text and indeed within the base text itself. Closer to the present day, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s haunting Dictee (1982) contains unannotated Korean and Chinese text throughout. One could imagine any number of variations of That is a mushroom: that is a mushroom / tHat is a mushroom / thAt is a mushroom / thaT is a mushroom / THAT IS A MUSHROOM / THAT IS A MUSHROOm, etc., but such examples are almost unimageable and would certainly not fall into the category of standardized variation. An example of standardized variation created within a particular text-world would be the use of eye-dialect, the non-standard spelling of words intended to suggest extra-textual information such as education, class, and race.

[6] Kennedy, Richard S., E.E. Cummings Revisited, Twayne, 1994: 131.

[7] I have translated “a leaf falls” into hitoha otsuru, the nominalized form of hitoha otsu in literary Japanese, to bring the phrase into agreement with “loneliness” (sabishisa), itself a noun.

[8] Gibson, William. Neuromancer. New York: Ace, 1984, 133-4.

[9] Gibson, William. Neuromancer. Trans. Hisashi Kuroma. Tokyo: Hayakawa Bunko, 2005, 233.