[2種類の文字・2つの言語]

『源氏物語』「帚木巻」に、藤式部丞が博士家の娘を久しぶりに訪ねた時に、娘から「月ごろ、風病重きにたえかねて、極熱の草薬を服して、いと臭きによりなんえ対面たまはらぬ」(=この幾月、風病が重くてたえがたかったので、解熱の薬草を服用して、それが臭いので対面をしていただくことができません)と告げられる場面がある。おもしろおかしく書かれた場面と思われるが、博士家の娘が、「はなしことば」中で、「フビョウ」「ゴクネチ」「サウヤク」といった漢語を使っていることもそのおもしろさに関わっていると推測する。

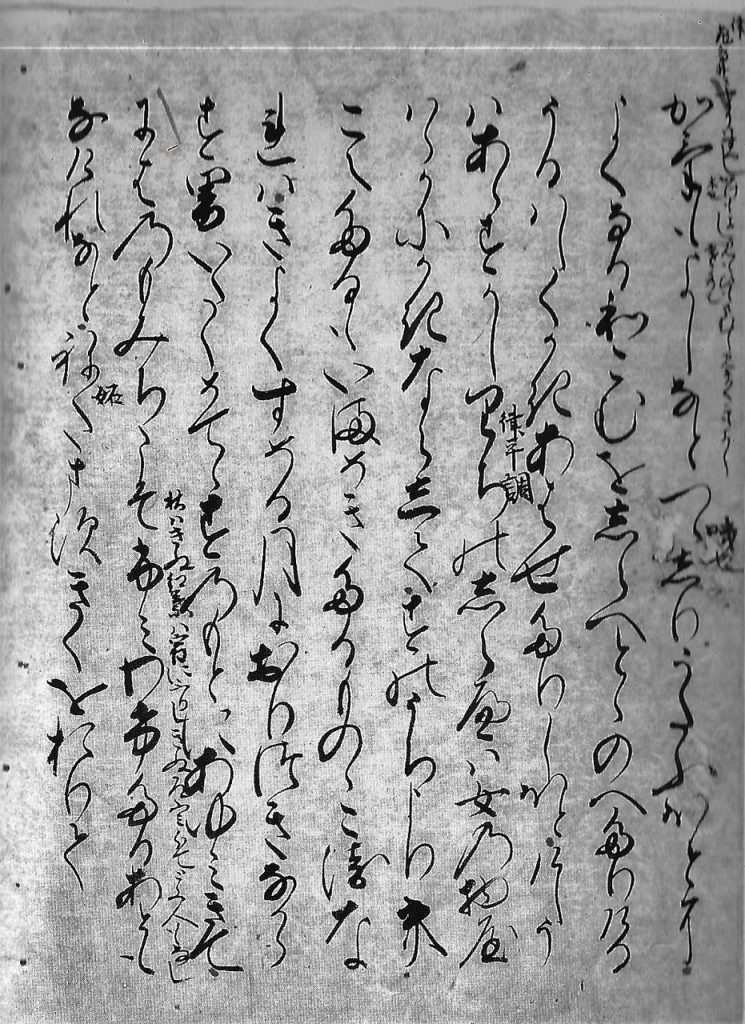

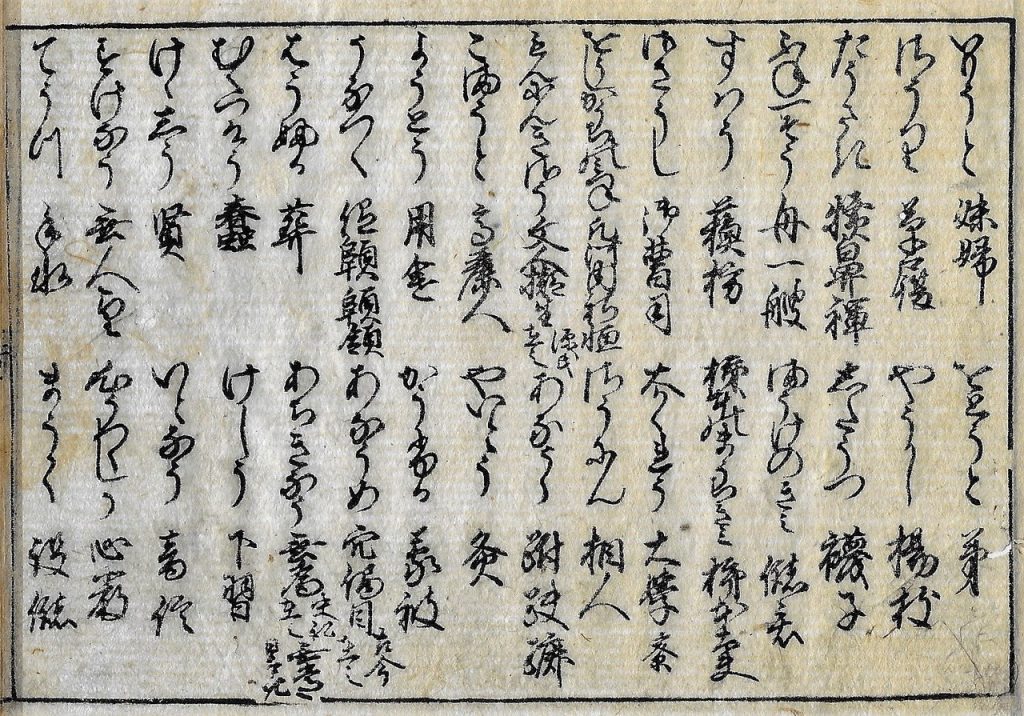

上ではそれぞれの語を、漢字列「風病」「極熱」「草薬」によって文字化したが、池田亀鑑『源氏物語大成』(1953-1956年、中央公論社)が「底本」とした「青表紙本」に属する「大島本」には「月ころふひやうおもきにたえかね/てこくねちのさうやくをふくして/いとくさきによりなんえたいめんたま/はらむ」(34丁裏9行目~35丁表2行目)と文字化されている。図1として「大島本」帚木巻の26丁裏を示したが、「大島本」はいろいろな書き込みがあるテキストであることがわかる。

書き込みはまさしく「行間注釈」であるが、1行目「かけもよしなとつゝしりうたふほとに」(「影もよし」などつづしり歌ふほどに)の「つゝしり」の右側に「A也」(Aは『大漢和辞典』が4247の番号を与えている、口×幾の形の字)、10行目「なけれなとねたますきくをおりて」の「ねたます」の右側に「妬」が傍書されている。

1行目の「つづしりうたふ」の「つづしり」は語義がわかりやすくはない語で、新日本古典文学大系『源氏物語 1』(1993年、岩波書店)の脚注31(51頁)には「少しずつぽつぽつと歌う歌い方か」とあり、「末摘花」巻にみられる「御つゞしり歌」に「一句ずつ短く切りながら口ずさむ歌のこと」という脚注をつけていることを紹介し、さらに12世紀後半にはできあがっていたと推測されている観智院本『類聚名義抄』において「A」字に「小食」という漢文注があることを示す。観智院本『類聚名義抄』をみると、「A」字には漢文注の他に「ツヾシル」「ツヽシム」「ヨフ」という和訓が配されている。

『日本国語大辞典』は「つづしる」の語義を「時間をかけて、少しずつ食べたりしゃべったりする。ぽつりぽつりと食べたり、物を言ったりする」と説明している。『源氏物語』「末摘花」の巻の使用はあげられていない。

『源氏物語』が成立したと推測されている11世紀の「読み手」には「ツヅシル」という語の語義は理解できたと思われるが、『日本国語大辞典』は江戸時代以降の使用例をまったくあげていない。そのことからすれば、江戸時代頃には「ツヅシル」はすでに理解できない、理解しにくい語になっていた可能性がたかいだろう。「ツヅシル」の語義がわからなくなっていた時期の「読み手」に「ツヅシル」という語の語義を簡略に教えるためにはどうすればよいか。和語「ツヅシル」の語義と字義が(ほぼ)同じと思われる漢字「A」示すのは一つのやりかたといってよいだろう。1行目の傍書「A」はそのような目的で書きこまれていると覚しい。

和語の語義を漢字によって示すというやりかたは、よく考えると不思議なやりかたともいえそうであるが、そうしたやりかたが行なわれてきた。表意文字としての漢字は日本語の内部に、日本語によって行なわれている言語生活に深くかかわっている。この例よりも10行目の例がわかりやすいだろう。10行目では「ネタマス」すなわち「ネタム」の右側に「妬」と傍書されている。常用漢字表も「妬」に「ねたむ」という和訓を認めている。

仮名は表音文字だから、仮名が並んで語をあらわす。仮名があらわしている語の語義を通常は、仮名からすぐに窺うことはできない。語が仮名によって文字化されている場合、「読み手」は並んでいる仮名が対応している語の発音にまずたどりつき、そこから語義を思い浮かべるというプロセスをひとまずはたどることになる。ただし稿者はそれ以外のプロセスがない、ということを述べようとしているのではない。「それ以外のプロセス」は「表音文字による表語はどのように行なわれるか」という問いについての検討につながる。

仮名は発音を喚起することにおいて力を発揮するが、語義の喚起力は必ずしも強くはない。上記の傍書「A」や「妬」はそれを補っているとみることができる。仮名に漢字が傍書されているのだから、漢字列に仮名を傍書する「振仮名」を一方においた場合、こうした傍書を「振漢字」と呼ぶことができるだろう。漢字に仮名を振る「振仮名」にしても仮名に漢字を振る「振漢字」にしても、漢字と仮名という2つの文字種があることが大前提となっている。アルファベットを使って文字化されている言語の行間に、同じアルファベットで注釈を入れても、わかりにくくなるだけであろう。視覚的にもはっきりと違いがわかる2つの文字種があることは「振仮名・振漢字」を成立させるための絶対条件といってよい。

さて、四辻善成(よつつじのよしなり:1326-1402)が貞治(1362-1368)の初め頃に、2代将軍足利義詮の命令によってつくった、『河海抄(かかいしょう)』という名の『源氏物語』の注釈書がある。書名は『史記』の李斯列伝の「河海不厭細流、故能成其深」(河海は細流を厭はず、故によくその深きことを成す)から採られている。この摘句は藤原公任(966-1041)が編纂した、漢詩・漢文・和歌を集めた朗詠のための詩文集である『和漢朗詠集』巻下「山水」にも収められている。『河海抄』は『源氏物語』研究を批判的に総合した画期的な大著として評価されている。

この原稿の末尾に、早稲田大学古典籍総合データベースにおいて公開されている『河海抄』巻1の画像(jpg77枚分)のリンクを示した。画像10枚目に、「桐壺」巻冒頭の「いとやんごとなき際にはあらぬがすぐれてときめき給ふありけり」のくだりについての注釈がみられる。

『河海抄』は、「いとやむごとなききはにはあるぬが」という『源氏物語』の「本文」を抜き出してその下に「無止事也」と漢字で注記し、次の行にも「亦停事也」「花容無止」と記し、「見万葉」と記している。また、「すくれてときめきたまふありけり」の下には「絶妙也」とやはり漢字で注記をし、「絶妙」には片仮名で「スクレ」と振仮名を施し、その下には「見日本紀」と記している。「やむごとなき」は「無止事也」である、という注記と思われるが、現代日本語母語話者の目からすれば、何を注記しているのかと思うような注記ともいえるだろう。これは仮名に漢字を添えることによって、(ほんとうにそうした効果があるかどうかは措くとして)何ほどかにしても語義を示す、表意をする、ということを目的としていると推測する。仮名で文字化されている語句に漢字を配して表意的な「情報」を添えるということがこうした形式の注釈の目的であろう。

画像11枚目においては「あちきなう」を「無為也」「無道也」「無状」「無事」「何須(右振仮名アチキナク)也」「無情也」「無端也」と説明し、それぞれの「典拠」を示している。このように、漢字列によって注釈をしている例を少しあげておくことにする。

| いとはしたなきこと 世のおほえはなやかなる わりなくまとはさせ給あまりに さがなきことども いとあえなくて | 無半事也 聲華也 無別 無破也 纏(右振仮名マトフ)也 不祥也 無悪善也 悪性也 不良也 最無敢也 専 イト |

15世紀以降に成ったと思われる『仮名文字遣』と名づけられている仮名遣書がある。源光行、その子の親行がほぼ完成させた『源氏物語』の注釈書である『水原抄』に加筆したことで知られる行阿(俗名は源知行で、親行は祖父にあたる)によって編まれた仮名遣書であるが、藤原定家とむすびつけられたために「定家卿仮名遣」「定家仮名遣」という書名となっているテキストもあり、江戸時代にも繰返し出版されている。

図2は刊記に「菊屋七郎兵衛板」とある江戸期に出版されたテキストの「う」の部であるが、12行目の下段に「あちきなう 無為[史記/在也] 無常/日本紀」とある。

『仮名文字遣』は仮名遣書であるので、かなづかいのみを示せばよいようなものであるが、仮名によってかなづかいを示しただけでは、それがどのような語であるか不分明な場合もあることに対しての「手当」と思われるが、『仮名文字遣』においては、ほぼすべての見出しに漢字列が添えられ、「仮名文字列+漢字列」が1つの項目の基本的な形式になっている。少し例をあげておくことにする。

| なをさりかてら | 等閑 | をとつれ | 音信 | 音 | (を部) |

| おほそら | 空虚 | おもひやる | 想像 | (お部) | |

| なからへ | 長久 | ゆうはへ | 夕栄 | 夕光 | (へ部) |

| つくろひて | 療治 | ねたひかな | 嫉妬 | (ひ部) | |

| さいはい | 幸福 | あはたゝし | 周章 | (は部) |

見出しに添えられている漢字列は見出しがどのような語であるかの理解を助けるために添えられていると思われるが、和語「アワタダシ」を漢字列「周章」によって文字化し、「あはたゝし」を振仮名とすることはできる。

先に述べたように、『仮名文字遣』は15世紀以降に成ったと推測されているが、『仮名文字遣』は室町時代に編まれた『節用集』と名づけられている辞書に引用されている。例えば、「小汀本」と呼ばれている、「印度本」に属するテキストの「を部」言語進退門に「不朧気(右振仮名ヲホロケナラス)小路(右振仮名ヲボロナリ)定」とある。この「定」が定家、すなわち『仮名文字遣』を指す。『仮名文字遣』の「お部」には「おほろけならす 不朧気 おほろけ也 朧」とあって、漢字列「小路」は見えないけれども、『仮名文字遣』の見出しが、このような形で、仮名遣書ではなく、辞書の体を成す『節用集』にとりこまれていることには注目しておきたい。辞書体資料としてとらえた場合、仮名遣書である『仮名文字遣』と辞書の体を成す『節用集』とは隣り合わせにあるといってもよい。『仮名文字遣』が『節用集』にとりこまれていることは、それを裏付ける。

仮名勝ちに文字化されている『源氏物語』の「本文」理解のために、仮名のそばに漢字を傍書する。仮名遣書において、見出しとしている語がどのような語であるかをわかるようにするために、仮名列の下に漢字列を添える。一見すると、両者には共通性がみえないが、前者を「振漢字」とみれば、「振漢字」は「振仮名」が反転したものということになるし、後者が仮名列の下に添えている漢字を仮名列の横に置けば、「振漢字」ということになる。そして、「振漢字」と「振仮名」とは仮名と漢字のどちらを「本行」に置くかという違いだけしかない、とみるならば、ともに2種類の文字による注釈とみることができることになる。

『節用集』の見出しには語釈が置かれていないことが多い。つまり、『節用集』は見出しのみの辞書ということになる。そして「平懐(右振仮名ナダラカ)」「密雲(右振仮名ナミダグム)」(「経亮本」ナ部言語門)のような「漢字列+振仮名」が見出しである。「平懐(右振仮名ナダラカ)」が見出しであるということは、漢字列「平懐」と和語「ナダラカ」が結びついていることを示すことが『節用集』にとって大事であることになる。2種類の文字、表意文字である漢字と表音文字である仮名とは、結局は中国語と日本語という2つの言語といわば「平行関係」にある。

日本語の中に借用語としての中国語=漢語が位置を占めている、ということは日本語の特徴の一つといってよいと考える。大げさにいうならば、日本語の歴史とは、中国語=漢語及び漢字を理解する歴史で、日本語を漢字を使って文字化するということ自体が日本語の歴史のある面を形成していったとみてもよいのではないだろうか。

振仮名が積極的に使われるようになったのは、江戸時代といってよいだろう。しかし振仮名を可能にしたのは、中国語と日本語という2つの言語、表意文字と表音文字という2つの文字で、その枠組みが「振仮名」を醸成し、それが江戸時代になって、製版印刷の常態化にともなって、顕在化したとみてもよいのではないか。「振仮名の可能性」は日本語の歴史そのものに内包されていたといったら強弁になるだろうか。

[振仮名が示唆すること]

「振仮名の可能性」というタイトルは、振仮名を使ってどのような言語表現が可能なのかについての言説が展開することを思わせるが、ここでは振仮名を注視することによって、日本語にかかわるさまざまな知見が得られるのではないか、ということを「振仮名の可能性」として述べてみたい。

慶應義塾大学附属研究所斯道文庫に蔵されている、室町時代書写と目されている、百二十句本『平家物語』(以下、斯道文庫本と呼ぶ)を観察対象とする。具体的には斯道文庫古典叢刊之二『百二十句本平家物語』(1970年、汲古書院)を使用する。挙例にはこのテキストのページ数を添える。

斯道文庫本は漢字片仮名交じりで文字化されている。原稿末尾に示したリンクをクリックすると、斯道文庫本のカラー画像を確認することができる。

冒頭ちかくをあげる。振仮名は漢字列の後ろに丸括弧に入れて示す。

奢(ヲゴ)レル人モ久シカラズ、只(タヽ)春(ハル)ノ夜(ヨ)ノ夢(ユメ)ノ如(ゴト)シ、猛(タケ)キ者(モノ)モ終(ツイ)ニハ亡(ホロ)ビヌ、偏(ヒト)ヘニ風ノ前(マヘ)ノ塵(チリ)ニ同シ

(5頁)

「春ノ夜ノ夢ノ如シ」に含まれている3つの「ノ」のうち、「春ノ夜」の「ノ」は「本行」ではなく右に寄って小書きされている。「風ノ前ノ塵」の「風ノ前」の「ノ」も同様に右寄せの小書きで書かれている。こうしたことについては検討する必要があると考えるが、今ここではそこには踏みこまないことにする。

上では「本行(ほんぎょう)」という表現を使ったが、小書きされた振仮名が施されているスペースにも「行」があるとみて、それを「振仮名行(ふりがなぎょう)」と呼び、その「振仮名行」に対して「本行」という表現、呼称を使用する。この「みかた」は金属活字で印刷されているテキストを考えるとわかりやすい。

上の引用では、振仮名と本行とを合わせると、「ヲゴレル人モ久シカラズ、タダハルノヨノユメノゴトシ、タケキモノモツイニハホロビヌ」となり、振仮名と本行とに重複はない。しかし、「遠(トホク)ク異朝(イテウ)ヲ訪(トブラ)ウニ」「近(チカク)ク本朝(ホンテウ)ヲ窺(ウカヽフ)ニ」の箇所では、「遠」の振仮名「トホク」、「近」の振仮名「チカク」は「ク」が本行と重複している。こうした箇所は一定数ある。以下では文字化を行なっている人物を「書き手」と呼ぶことにする。

「遠(トホク)ク」を例にとって考えるならば、書き手は「トホク」という語を漢字「遠」と片仮名「ク」によって「遠ク」と文字化した。その後、「遠」に「トホク」と振仮名を施した。振仮名を施している書き手は振仮名を施している「瞬間」は読み手になっているといってもよい。書き手は自身が文字化した本行に、読み手となって振仮名を施す。ここにおいて、書き手と読み手とが双方向的な存在となっている。

「遠」に「トホク」と振仮名を施したのは、「トホク」が「遠」と結びついている和訓であったからで、さらにいえば「定訓」にちかい和訓であったことが推測される。本行に「ク」が記されていて、すでに「遠ク」とあるにもかかわらず、「トホク」を振仮名にしたのは、(もちろん本行に「ク」があることからすれば、うっかりしていた、すなわち錯誤であることになるが)「トホク」が切れ目のないひとまとまりのものであったからで、内部に「休止のない」(宮岡伯人(2015:70))、「切れ目のないひとまとまりのもの」を言語単位としての「語」の定義とするならば、この「遠(トホク)ク」という文字化によって、振仮名を施した人物にとって「トホク」が1語であったことを示唆すると考える。ただし、これは振仮名と本行とに重複がある例をもって、そうしたことが推測されるということであって、「亡(ホロ)ビシ者(モノ)ドモ也」においては、重複がないのだから、「亡」の振仮名「ホロ」が1語と認識されていたということにはならない。この場合は「亡ビシ」に対して「ホロ」という、過不足がない振仮名を施しており、当然のことながら、多くの場合、振仮名と本行は重複しない。

「今夜(コヨイ)イ」(7頁8行目)において、書き手は漢字列「今夜」が漢語「コンヤ」ではなく和語「コヨイ」であることを示すために、まず「イ」を漢字列「今夜」の後ろに附した。しかし、振仮名を施すにあたって、漢字列「今夜」と「コヨイ」の結びつきが強かったために振仮名も「コヨイ」とした。本行に合わせて振仮名を「コヨ」としなかったのは、「コヨイ」が「切れ目のないひとまとまりのもの」すなわち1語、しかも形を変えない名詞であったからと推測する。

此(コ)ノ禅門(ゼンモン)ノ世盛(ヨザカリ)ノ間(アイタ)ハ、聊(イサヽ)カ、人ノ聞(キカ)ネハトテモ、坐(スヽロニ)ニ申(マウ)ス者(モノ)ノナシ

(13頁6-7行目)

「坐(スヽロニ)ニ」の箇所では、「ニ」が重複している。これも「坐」の(おそらく定訓といってよい)和訓が「ススロニ(スズロニ)」であったために、「坐」に「スヽロニ」というひとまとまりの和訓を施したと思われる。

ここまで述べてきたことでわかるように、「振仮名」という事象は「漢字列がどのような語をあらわしているかを示す」「漢字列のよみを示す」ということを超えて、振仮名が施された時期の日本語のありかたと深くかかわっている。江戸期、明治期の振仮名の観察によってわかるように、振仮名が日本語の表現として機能していることはいうまでもない。さらに、日本語のありかたと深くかかわっている振仮名を丁寧に観察することによって、日本語にかかわる知見を得ることができる。そして、中国語と日本語という2つの言語、表意文字である漢字と表音文字である仮名という2つの文字種が振仮名を成立させているが、それが日本語そのものの「枠組み」でもあることに留意しておきたい。

参考文献

宮岡伯人 2015 『「語」とはなにか・再考 日本語文法と「文字の陥穽」』(三省堂)

大島本『源氏物語』帚木巻26丁裏 早稲田大学総合古典籍データベース https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/bunko30/bunko30_a0080/bunko30_a0080_0001/bunko30_a0080_0001.pdf

菊屋七郎兵衛板『仮名文字遣』30丁表 斯道文庫本の画像

https://www.fl-keio.info/fl_img/course01/detail/092_To45_11_003.html

The History of Furigana

Konno Shinji, trans. Chris Lowy

Chapter 01 Part 02: Furigana in Contemporary Fiction

In this section I refer to the following pieces of fiction and discuss how furigana is used in them. Page numbers appearing in parenthesis throughout this section refer to the versions of the text listed below.

- Nakagami Kenji, The Kareki Sea (Karekinada; Kawade shobō shinsha, May 1977)

- Ōe Kenzaburō, The Game of Contemporaneity (Dōjidai geemu; Shinchōsha, November 1979)

- Murakami Ryū, Coin Locker Babies, vols. 1 & 2(Koinrokkaa beibiizu; Kōdansha, October 1980)

- Inoue Hisashi, Kirikirijin (Shinchōsha, August 1981)

- Maruya Saiichi, Kimigayo – Sing it in Falsetto! (Uragoe de utae kimigayo; Shinchōsha, August 1982)

Can one write Japanese without furigana?

Murakami Ryū’s Coin Locker Babies does not have much furigana in it. There are around 21 examples to cite in all 257 pages of volume one: 目眩 (memai, vertigo; pg. 4), 飯事 (mamagoto, playing house; 7), 転た寝 (utatane, a nap; 14), 魚籠 (biku, wooden fish basket; 16), 塗れて (mamirete, smeared with [x]; 16), 大鋸屑 (ogakuzu, sawdust; 18), 戦いでいる (soyoideiru, [to be] rustling; 21), 栄螺と雲丹 (sazae to uni, turbo and sea urchin; 39), 牡蠣殻 (kakigara, oyster shell; 55), 罅割れたセメント (hibi wareta semento, cracked cement; 87), 鬘 (katsura, a wig; 88), 嗄れ声 (shagaregoe, a hoarse voice; 125), 嵌めかえた (hamekaeta, to replace [e.g., a tire]; 133), 掠れて (kasurete, to become hoarse; 169), 流行る (hayaru, to become popular; 172), 蜥蜴 (tokage, lizard; 178), 象嵌 (zōgan, inlaid work; 203), 齧る (kajiru, to gnaw; 137), 顳顬 (komekami, the temple; 250), and 臑 (sune, the shank; 250). A reader would, on average, encounter furigana roughly once every twelve pages. The impression one gets when reading the text is that furigana are almost non-existent. This is also the case in newspapers today, too. You could say that written Japanese today has settled on a style that combines Sinographs and kana (i.e., hiragana and katakana) and makes little to no use of furigana.

This, of course, hasn’t always been the case. For example, it was common to see foreign toponyms written in Sinographs that were largely incomprehensible without the addition of furigana: 瑞西 (suisu; Switzerland), 地羅利 (chiroru; Tyrol), 毫破里 (neepurusu; Naples), or 亞爾伯 (arupusu; the Alps), to name just a few. Today such place names are generally written in katakana so there is no need to use furigana.

Looking back on the history of furigana from today’s perspective, it seems reasonable to start with the assumption that Japanese can be largely written without furigana. That being the case, we should then pay attention to the situations in which furigana are being used. If we look at Coin Locker Babies, the majority of cases of furigana are terms such as memai (目眩; vertigo) and ogakuzu (大鋸屑; sawdust), words that are written in so-called “difficult” Sinographs. “Difficult” here refers both to Sinographs that are not widely known (e.g., 顳顬) as well as associations between common Sinographs and common words that are not widely known (e.g., soyogu and 戦).[1] In both cases we might say that difficult Sinographs have been used, with furigana showing the precise word one is intending to write. At the end of the day, then, these are furigana-as-readings.

Furigana and dialect: the case of the Kirikiri language

The Kirikiri language is used throughout Inoue Hisashi’s Kirikirijin. It is a language closely resembling the Tohoku dialect of northern Japan, with the text explaining that it is “a language that broke away from the Japanese language no later than the early Edo Period” (75). The language appears as furigana throughout the text so much so that it becomes painful for the reader. In the third part of the book there is even a set of practice exercises designed to help one master Kirikiri. It is not surprising, then, that Kirikiri plays an important role in Kirikirijin. Below is one passage from the text. I have done my best to preserve the original visual representation. Note that bolded words that appear in either Latin transcriptions indicate words that have furigana attached to them in the original, dzu in the transcription represents づ, and non-initial capital letters represent miniscule or otherwise unconventional uses of katakana. The transcription of the base text is largely hypothetical: the use of dialect (e.g., the ending dacha in the first sentence) suggests that the entire text ought to be read in Kirikiri.

| Original text | ビッグショー言えば、N H Kの看板番組だっちゃ。妾も時々、見る事、あるでした。妾の見だなァ越路吹雪だべ、美空ひばりだべ、北島三郎だべ、五木ひろしだべ、…。兎に角、一流の芸人ばっかりス、この番組さ出られんのは。すっと、ちまり貴方の母様も一流の芸人なんだね。だども、悪ィけっとも、名前は聞いだ事ァないなあ。言う事はオペラ歌手か何かで御座居すか?(455) |

| Transcription of base text | Biggusho ieba, NHK no kanban bangumi daccha. Watashi mo tokidoki, miru koto, arudeshita. Watashi no midanaA Koshiji Fubuki dabe, Misora Hibari dabe, Kitajima Saburō dabe, Itsuki Hiroshi dabe, … Tonikaku, ichiryū no geinin bakkariSU, kono bangaumi sa derarenno wa. Sutto, chimari anata no kaasama mo ichiryū no geinin nandane. Dadomo, waruI kettomo, namae ba kiida koto A nainaa. Iu koto wa opera kashu ka nanika de gozaimasuka? |

| Transcription of furigana | Beggusoo tsu ieba, NHK no kanban bangumi daccha. Wadasu mo togidogi, mitsu kodo, andeshita. Wadasu no midanaA Kosudzu Funbuki dabe, Mesorai Ibari dabe, Ketadzuma Saburo dabe, Ezugi Herosu dabe, … Tonukagu, edzuruu no geenin bakkariSU, kono bangaumi sa derarenno wa. Sutto, chimari anda no kaacha mo edzuruu no geenin nandane. Dadomo, wariI kettomo, namae ba kiida godaA neenaa. Tsuu goto wa okera kasu ka nanka de gozeesuka? |

| Translation | Oh yeah, Big Show, it was a popular program on the NHK. I’d also watch it from time to time. Who’d be on it… let’s see, Kosudzu Funbuki [Koshiji Fubuki], yeah, and Mesorai Ibari [Misora Hibari], Ketadzuma Saburo [Kitajima Saburō], and Edzugi Hirosu [Itsuki Hiroshi]. In any event, it was all first-rate entertainers on the show. Which means your mother, too, is a first-rate entertainer. But I must apologize, I’ve never heard her name before. Is she some sort of opera singer or something? |

Here, even words of foreign origin such as Big Show and opera, and people’s names like Koshiji Fubuki and Misora Hibari, have furigana attached to them to indicate their pronunciation in the Kirikiri language. We can understand these furigana as indicating a non-standard pronunciation. The case of 妾, however, is a little different. One could write the first-person pronoun wadasu in hiragana (and thus without using Sinographs). If one writes wadasu in hiragana then there would, of course, be no need for furigana. Following this pattern we might anticipate すると or つまり, but they are not written in this way.

In other words, it is possible to visually represent the pronunciation of words in the Kirikiri language by using kana. The above excerpt contains examples of kana that indicate a Kirikiri pronunciation and kana that do not. There are two patterns we see in those instances that do not indicate this pronunciation: (i) there are cases that necessitate furigana because Kirikiri words are written in Sinographs, and (ii) cases where words like ない, despite being written in kana, indicate the general or standard word-form in the base text but have furigana attached to them so as to indicate the Kirikiri language thus to draw a comparison between the two.

One major theme of Kirikirijin is the relationship between the center and the periphery, with the center tied to the modern standard language and the periphery tied to the Kirikiri language. This format allows for an unfamiliar but significant contribution to the Japanese literary sphere, a contribution that is represented in Japanese as 共通語 (base text: the standard language; furigana: the Kirikiri language).

Inoue Hisashi’s “Considering the Advantages and Disadvantages of Furigana”

In addition to writing Kirikirijin, Inoue Hisashi also penned Shikaban Nihongo bunpō (A Personal Grammar of the Japanese Language, 1981) which contains the section “Rubi wa son ka toku ka kangaeru” 振仮名損得勘定 (Considering the Advantages and Disadvantages of Furigana).[2] This essay contains Inoue’s clearest thoughts on furigana.

In “Considering Furigana,” Inoue introduces Yamamoto Yūzō’s essay “Furigana haishi ron” (An Argument for Abandoning Furigana) – a text I also discuss in the Conclusion to this book – and, with Yamamoto’s reference to furigana as “black bugs” (kuroi mushi) in mind, says

the large increase in furigana use is in line with the trend for the intellectual pleasures of a select few to become something the masses were starting to enjoy. That is, from late Edo through Meiji, pleasure and entertainment rooted in intellect and knowledge spread far and wide on the back of those black bugs we call furigana.

He continues,

to put it another way, furigana is a valuable tool that links Sinographs to kana (i.e., meaning) and to sound. If we spray anymore insecticide on those hard-working black bugs the Japanese language would fall apart. I don’t think we should get carried away by things such as the processes of mass popularization (taishūka) and rationalization (gōrika). (106-7)

When special word-forms become furigana

郁男は何度も何度も鉄斧や包丁を持って、路地の家から「別荘」の辺りにある義父の家へ、フサと秋幸を殺しにきた。

(Nakagami, 108)

Time and time again Ikuo took hold of a hatchet or cleaver and left his home in the alley to go kill Fusa and Akiyuki at his stepfather’s place near the villa.

年は十九で、虚無僧なさる。

(212)

He was nineteen and living as one of those basket-wearing mendicant monks.

徹が「ちょっと竹原の本家へ寄ってくれ」と言ったので秋幸は車を仁一郎の家の前で止めた。

(216)

Akiyuki parked his car in front of Jin’ichirō’s place because Tōru told him to pass by the Takehara’s family home.

One finds the following explanation under the entry for 斧 (hatchet; axe) in the Wamyō ruijushō 和名類聚抄, an important 10th century Japanese dictionary of Sinographs: 音府和名乎能一云與岐 (On fu, wamyō ono, hitotsu ni iu yoki), or The Sino-Japanese reading [on] is fu; the Japanese vernacular term [wamyō] is ono, another one is yoki. From this explanation we know that the Sino-Japanese reading of Sinograph 斧 was fu and its associated vernacular Japanese readings were, at least, ono and yoki. Put another way, this confirms that already by the 10th century the reading of yoki for 斧 was well established. Today there are more than a few dialects that refer to a small hatchet with the word-form yoki, with the above excerpt from The Kareki Sea being one example. Nevertheless, yoki is an archaism that, despite surviving in a handful of dialects, is not comprehensible to speakers of modern standard Japanese; yoki is a special word-form and indicated as such with furigana. 虚無僧 (komonso) is also a special word-form. Similarly, if the two-character Sinograph string 本家 did not have furigana attached to it readers would likely assume it is to be read honke. Here, however, the furigana tells us it represents the dialectal variant hon’ya. As we see in these examples, if one writes special word-forms with Sinographs – for example, contrasting the dialectal word-form of a term with its modern standard equivalent by utilizing standard Sinographs – then one must use furigana to indicate that special word-form otherwise the desired communication cannot occur. Here, Sinographs serve as a point of connection between a modern standard word-form and a special word-form.

Sinographs connecting two word-forms

In The Kareki Sea one also encounters the term 木馬 (9). We can imagine that the furigana here, read kinma, illustrates a sound change from kiuma or kimuma into kinma. The etymology of kinma, however, is ultimately derived from ki no uma (lit., “horse of wood”), though in this text it is referring not to a wooden horse but to wooden sled used to transport lumber. In a way, the two-character Sinograph string 木 (ki; tree/wood) and 馬 (uma; horse) illustrate this etymology. On the other hand, the character-string 木馬 is usually read mokuba and refers to a horse-shaped object made out of wood (e.g., a rocking horse). The moment one writes the character string 木馬 the associations with the usual reading of mokuba bleed through from behind the Sinographs.

In cases where the meaning of the Sino-Japanese word mokuba and the meaning of the term kinma (as indicated by the furigana) are superimposed on top of each other, the furigana (kinma) and the Sino-Japanese word (mokuba) hiding behind those two Sinographs are linked by the Sinographs. Thus, the Sinographs aid in understanding the meaning of the term indicated by furigana. This also means that in instances such as kinma and mokuba, where the term written in furigana and the meaning of the Sino-Japanese word peeking from behind the Sinographs are different, the furigana are simultaneously announcing that the two are different. In any case, we ought to pay attention to the fact that Sinographs can function as the link between two word-forms: the surface word-form indicated by furigana and the Sino-Japanese word-form(s) hiding in the background.

Though somewhat of an outlier, I will introduce another example that illustrates this point nicely. In Maruya Saiichi’s Kimigayo – Sing it in Falsetto! (Uragoe de utae kimigayo) we meet a character named林清禄, “the son of a Taiwanese couple living in Shizuoka Prefecture (though their nationality is in fact Japanese)” (97). The novel depicts a scene in which this character meets someone for the first time:

林でございます。どうぞよろしく。」と挨拶し、名刺を出した。

“I’m Hayashi, nice to meet you,” he said and took out his business card.” (94)

Here, 林清禄 introduces himself with the Japanese name Hayashi, typically written 林. Throughout the text we see other examples of this type:

さうなんですか。リンさんがハヤシさんになつたわけですね。

“Is that so? So, Mr. Rinbecame Mr. Hayashi. (96)

This issue can arise when the same Sinographs are used in Taiwan, China, and Japan. While the meaning of the Sinograph 林 might be the same in all of these places (whatever “same” means), the possibility of reading it as either Hayashi (which, in this case, suggests a Japanese national) or reading it as Rin (which suggests a Chinese or Taiwanese national) is an example of how Sinographs can link two word-forms and two languages.

Words written in katakana

Ōe Kenzaburō’s The Game of Contemporaneity (Dōjidai geemu) contains numerous examples of Japanese words written neither in Sinographs nor hiragana but katakana, the character set usually tasked with writing words of foreign origin. A few examples are 貼りボテ (haribote, papier-mâché; 207) ガランドー (garandoo, void; 329), ウワゴト (uwagoto, delirious or incoherent speech; 393), and ブレている (bureteiru, to be blurred [i.e., a photograph]; 400). Each of these terms are, in a sense, difficult to write in Sinographs – even dictionaries might not provide a list of Sinographs used to write them. If one is determined to write them in Sinographs – for example, 囈言 (uwagoto) or 伽藍堂 (garandō) – then attaching furigana to them becomes necessary. On the other hand, within the same text there are examples such as 蕈 (kinoko, mushroom; 324), a word often written in hiragana but here written not only in a Sinograph but in a less common one at that.[3] Similarly, words such as バネ (bane, a spring; 87), カラクリ (karakuri, a mechanism; 222), and ガラクタ (garakuta, junk; 327) are not written in Sinographs or in (the usual) hiragana character set. Again, if there was a strong desire to write them using Sinographs (or if one were compelled to use them by some outside force) there are options: 発条, 機関, and 我楽多, respectively. These words stand out to the reader for no other reason than that they are written in the katakana character set.

A phonetic character set such as hiragana or katakana that represents individual syllables allows one to write any word in the language. If we place these phonetic kana on the extreme of one end of a spectrum, then we can also place the logographic Sinographs on the other extreme of the same spectrum.[4] Sitting somewhere in the middle is the meeting point of these two: 漢字 (Sinographs and furigana). We can diagram this relationship as

| 仮名 | ⇔ | 漢字 | ⇔ | 漢字 |

| Kana | ⇔ | Sinographs/furigana | ⇔ | Sinographs |

If there is either strong internal or external pressure to write karakuri in Sinographs then からくり or カラクリwould become 機関, but if there is pressure to write 機関 in kana it becomes からくり or カラクリ. Additionally, if there was a strong desire to write in the alphabet, we would get KARAKURI (or some variation therein).

When we consider that the company previously named 稲毛屋 (Inageya) changed its name to いなげや (Inageya), the bank 駿河銀行 (Suruga ginkō) changed its name to スルガ銀行 (Suruga ginkō), the pharmaceutical company 津村順天堂 (Tsumura juntendō) became simply ツムラ (Tsumura), the automotive component manufacturer 豊田紡織 (Toyota bōshoku) became トヨタ紡織 (Toyota bōshoku), the frozen food producer 日本冷蔵 (Nippon reizō) became ニチレイ (Nichirei), and 能率風呂工業 (Nōritsuburo kōgyō) became ノーリツ (Nooritsu), we can see the desire to write in Sinographs has shifted to a desire to write in kana. The three cities of 浦和 (Urawa), 大宮 (Ōmiya), and 与野 (Yono) of Saitama Prefecture combined to become さいたま市 (Saitama-shi, Saitama City) while similarly the town of 秋川 (Akigawa) and the city of 五日市 (Itsukaichi) in the Tokyo metropolis combined to become the city of あきる野 (Akiruno). In Chiba Prefecture there is the city of いすみ (Isumi) and in Fukuoka there is みやま (Miyama). To be honest, I was somewhat taken aback by the emergence of city names written in hiragana. We might also think of this period as one in which the desire to write in the alphabet is strong: 飯山電機 (Iiyama denki) became イーヤマ (Iiyama) before settling on Iiyama, 伊奈製陶 (Ina seitō) became INAX, 東京電気化学工業 (Tokyo denki kagaku kōgyō) became TDK, and 東洋陶器 (Tōyō tōki) changed its name 東陶機器 (Tōtō kiki) before becoming TOTO.

[1] [To elaborate just a bit more, the word soyogu, meaning “to rustle; to sway” and the Sinograph 戦 are both commonly encountered in modern Japanese. It is the combination of the two, namely, 戦ぐ, where the reader needs to associate the term with the Sinograph, that is not widely known and thus “difficult.” In this particular case the situation is exacerbated because the Sinograph 戦 is typically read as either sen or tatakau, meaning “to do battle [with X].”]

[2] [The base text of the title provides furigana in Sinographs 振仮名 while the actual furigana reads this character string as ルビ rubi, or “ruby,” another term for furigana that has its roots in printing culture.]

[3] [The Sinograph 茸 is more commonly associated with kinoko.]

[4] [It is important to note that no script is either fully phonetic or logographic. A fully phonetic script such as the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is, in nearly all cases, too unwieldy and unnecessary for everyday use, while a purely logographic script does not, and likely cannot, exist. Indeed, Konno’s words here are more nuanced: he says 表音系文字 (hyōonkei moji) and 表意系文字 (hyōikei moji), phonetic-type script and logographic-type script.]