今野真二

第7回は振仮名を話題にするが、江戸期の振仮名と明治期の振仮名との2回に分けて述べることにする。両時期の振仮名を、それぞれの時期の表記システムにおいて、どのように位置づけるかということは今後明らかにする必要がある課題であると考える。

まず振仮名について整理しておきたい。

日本語学会編『日本語学大辞典』(2018年、東京堂出版)の見出し「振り仮名」においては振仮名を「日本語表記において、漢字に小さく傍記してその読み方を示す仮名。付け仮名、助仮名などともいう」(802p左:矢田勉執筆)と説明している。

おおむね首肯できる説明といってよい。しかし、例えば、鶴亭秀賀作、歌川国貞画『金華七変化』(1860-1870刊)のような草双紙(合巻)においては、「將軍[せう/ぐん]」「黄泉[おう/せん]」(初編上冊4丁表)([ ]は細字双行になっていることを示す。/は改行の位置)のように、漢字列の傍らではなく、直下に割書のかたちで、直前の漢字列についての「情報」が置かれていることがある。

草双紙は平仮名に少数の漢字を交える「平仮名漢字交じり」の「表記体」で文字化することを、草双紙という媒体=メディアが選択しているといってよい。いいかえれば、そうした「表記体」を採ることが草双紙というメディアを支えていることになる。

草双紙の版面をみればすぐにわかるが、奇数丁裏と偶数丁表が見開きになり、その見開きを単位として挿絵が描かれていることが多い。文字は絵の間を埋めるようにして配置されており、見かけ上はどちらかといえば挿絵が主、文字が従にみえる。こうしたテキストの場合、挿画は「(行間)注釈」というよりは、テキスト全体にかかわる要素とみるべきであろう。当然こうしたテキストの「表記体」を考えるにあたっても挿画があることを十分に考慮する必要があることは疑いない。そして、そのような「表記体」であるために、草双紙においては漢字の傍らに振仮名を施すことができない。

振仮名を施すことができないということが漢字の使用に一定の制限を与えていることは容易に想像することができる。多賀糸絵美(2012)は草双紙において使われている漢語が「漢語辞書の語釈に現れる漢語群と一致する」ことを指摘している。振仮名によって、例えば、語義にかかわる「情報」を付加することができないとなれば、そうした「情報」なしに「読み手」が理解できる漢語を使うということはむしろ当然のことといってよい。

現在刊行されている小型の国語辞書、例えば『三省堂国語辞典』第8版においても、漢字列の直下に割書のかたちで「直前の漢字列についての「情報」」が置かれている。漢字の傍らに振仮名を施すためには、版面にゆとりが必要で、そうしたゆとりがない場合には、振仮名を使わないか、上記のように、漢字列直下に振仮名が担うような「情報」を置くしかない。これは物理的な(という表現を使っておくが)版面が「表記体」に影響を与えるということを示している。つまり、「物理的な版面」のような、テキストの具体的なあり方がテキスト全体のあり方を左右する可能性がある。

また、明治期に刊行されたテキストは、当初は製版印刷されることが多かったと思われるが、金属活字の広通と西洋風の製本技術の浸透にともなって、次第に活字印刷されるようになっていく。いわゆる「ボール表紙本」は西洋風の製本技術がゆきわたらない時期の過渡的な製本といえるが、明治20年代頃までに多く出版されている。このことからすれば、明治20年代あたりを画期として、具体的な文字化のしかたも変化していくことが推測できる。

活字印刷において振仮名を使用するためには、振仮名用の活字を置く行を設定し、そこに「本文」よりは小ぶりの活字を植字する必要がある。振仮名用の活字は小ぶりであるために、実際の印刷において、位置がずれたり、転倒したり、場合によっては一部がなくなったりすることが起こる。つまり、振仮名をきれいに施した状態で活字印刷をまっとうすることは技術的にも簡単ではない。そうであれば、振仮名はどうしても必要な場合にのみ施すということになるだろうし、想定される「読み手」とのかねあいで、振仮名をまったく使わないという選択が行なわれることもあったと推測される。振仮名をまったく使っていないテキストが、振仮名を必要としない「読み手」を想定してつくられていることはもちろんあろうが、やむをえず振仮名を使っていないということもまたあり得ることと考えておく必要がある。そう考えると振仮名が施されているから、この語を文字化したものだとわかるが、振仮名が施されていなければそれがわからないという「みかた」は一つの「みかた」として首肯できるものの、場合によっては表層的な「みかた」ということになる。そう考えると、明治期の振仮名については、最終的には振仮名を施していないテキストを視野にいれてとらえる必要があると考える。

上記では振仮名について「漢字列についての「情報」」と表現した。先に引用した『日本語学大辞典』の記事は、振仮名を「漢字に小さく傍記してその読み方を示す仮名」と説明している。「基本的機能と用法」については別途丁寧に述べられているが、それは振仮名の「基本的機能と用法」という説明であって、振仮名を、いわば外側から説明はしていない。その外側からの説明として「漢字列についての「情報」」というとらえかたがある。これはさらに抽象度をたかめれば「(行間)注釈」ということになる。振仮名が「情報」を付加している、「注釈」を施している、ととらえることによって、振仮名という概念を広くとらえることができ、そのようにとらえかたの抽象度をたかくすることによって、概念が汎用できるようになる。

振仮名が「注釈」や付加情報である以上、そのことが読み手にとって明示的である必要がある。したがって、振仮名が「本文」の漢字よりも小ぶりであることは振仮名が振仮名であるためには必須であることになる。また、(ここでは漢字であるが)「本文」の文字体系とは異なる文字体系であると「本文」ではないことがいっそう明示的になる。日本語における振仮名は、(基本的には)漢字に、当該漢字よりも小ぶりな仮名で施されることによって、振仮名であることの基本条件を充足させているといえるだろう。このように考えると、ほとんどが平仮名によって文字化されている「本文」に小ぶりの漢字を添えることによって「注釈」する場合は、振仮名という名称にはそぐわないけれども、機能としては振仮名と同等であり、広義の振仮名に含めることはできると考える。

以下では滝沢馬琴の読本『南総里見八犬伝』を観察対象として、江戸期の振仮名について考えてみたい。『南総里見八犬伝』第2回(23丁裏)に次のようなくだりがある。

われとにかくに懶(ものくさ)くて。久しく城外へ出ざりき。今你達(なんたち)が/ 諫言(かんげん)は口苦からぬ良薬(りやうやく)とおぼゆれは。翌(あす)は早旦(つ とめ)て狩倉(かりくら)すべきに。まづこの/旨を令(ふれ)しらして。准備(よ うゐ)させよ。

当該テキストはほとんどすべての漢字に振仮名を施しているが、多くの振仮名を省いて引用する。残した振仮名は漢字列の後に丸括弧に入れて示す。

漢語「カンゲン」「リョウヤク」をそれぞれ漢字列「諫言」「良薬」によって文字化することは、漢語を漢字を使って文字化するということをも含めて、もっとも自然な文字化といってよい。

江戸期においても、これらの漢語は、現代日本語と同じように「カンゲン」「リョウヤク」と発音されていたであろうから、振仮名「りやうやく」は、江戸期においても「ストレート=表音的」な文字化ではなく、「かなづかい的な文字化」であったことになる。「ストレート=表音的」な文字化をしていないことについては考えておく必要があるが、今ここではそのことにはふみこまない。そして、「りようやく」ではなく「りやうやく」と「かなづかい的な文字化」をしているけれども、これを今ここではほぼ表音的であるとみなすことにする。そうみると、振仮名「かんげん」「りやうやく」は当該漢字列があらわしている語の発音を示していることになる。

上では省いたが、当該テキストにおいては「久しく」の「久」には「ひさ」と、「今」には「いま」と振仮名が施されている。この「ひさ」は「久しく」という文字列が全体として「ヒサシク」という語をあらわしていることを示しており、「いま」という振仮名は単漢字「今」が「イマ」という語をあらわしていることを示しているという点において、やはり「当該漢字列があらわしている語の発音」を示す振仮名ということになる。「読み手」の立場からいえば、「当該漢字列があらわしている語のよみ」を示している振仮名ということになる。

「久」「今」は平成22(2010)年に改定された常用漢字表に載せられており、かつ「ひさしい」「いま」はそれぞれの漢字の訓として認められているので、「当該漢字列があらわしている語の発音」ということが現代日本語母語話者にもわかりやすい。

「翌」も常用漢字表に載せられているが、この漢字には訓が認められていない。現代日本語母語話者にとっては、漢語「ヨクジツ」をもっとも自然に文字化した漢字列「翌日」に「あす」と振仮名が施されていたほうがあるいはわかりやすいかもしれないが、「翌」が「翌日」の「翌」であることに思い至れば、単漢字「翌」に「あす」と振仮名が施されていることが納得できるかもしれない。

ここで何がおこなわれているかといえば、漢語「ヨクジツ(翌日)」の語義が〈あくる日〉であること、和語「アス」の語義がやはり〈あくる日〉であることを確認して、漢語「ヨクジツ」と和語「アス」の語義に重なり合いがあることを確認した上で、だから、漢語「ヨクジツ」に使う漢字列「翌日」の「翌」と和語「アス」とを結びつけることができるということを理解するという「確認」であろう。それを少し集約的、圧縮的に表現するのであれば、漢語「ヨクジツ(翌日)」と和語「アス」との語義の重なり合いを背景にして、「翌日」の「翌」と和語「アス」とを結びつけるということになる。

上記の説明はだいぶ「まわりくどい」けれども、漢字2字で文字化される漢語の語義を2字のうちのどちらかの漢字と結びついている和語によって理解するということは平安時代頃からずっと行なわれているとみてよいだろう。

例えば、「かくて志気(こゝろざし)あるものは。主を諫めかね/て身退き。又勢利(いきほひ)に憑(つく)ものは。をさ々々媚て定包(さだかね)が尾髯の塵をとりしかは」(21丁裏)(々々は繰返し符号に仮にあてた)の漢字列「勢利」は〈権勢と利欲〉という語義をもつ漢語「セイリ」にもっとも自然にあてられる漢字列であるが、「勢利」を「権勢」「利欲」という2つの語義に分けて理解するのではなく、語全体を和語「イキオイ」で理解した振仮名といえよう。これは、「読み手」の側からの説明であるが、「書き手」の側からいうならば、「イキオイ」という抽象度のたかい和語を文字化するにあたって、当該文脈の具体的な語義にあわせて、漢語「セイリ」に使われる漢字列「勢利」をここでは選択した、ということになる。したがって、いついかなる時でも和語「イキオイ」を漢字列「勢利」によって文字化するということではない。実際、少し先の箇所には「這奴(しやつ)は威勢(いきほひ)国主に/まして」(22丁裏)とあり、この箇所においては、和語「イキオイ」を漢語「イセイ(威勢)」に自然にあてる漢字列「威勢」によって文字化している。振仮名が「注釈」「付加情報」である以上、同じ「注釈」が異なる漢字列に加えられる場合は当然あるし、文脈如何によって、異なる「注釈」が同じ漢字列に加えられる場合もあることになる。

今ここでは、「書き手」である滝沢馬琴が和語の文字化にあたって、当該和語の語義にあわせて、文字化に使う漢字列を変えているということを前提にしている。上記2例のみでそう断言することは当然ながらできないが、おおむねそのようにみえる。そうであれば、中国語に比して抽象度がたかい日本語を文字化するにあたって、日本語より具体性をもつ中国語すなわち漢語の語義の違いを使って、和語の抽象性を補っていることになる。そう考えることができるならば、和語を漢字によって文字化するという文字化のプロセスにすでに日本語にはない「情報」の付加がある(場合がある)ことになる。

接触が長く深い中国語の語彙を借用するということだけであれば、それはどの程度の語彙を借用しているか、ということにとどまるが、日本語を漢字で文字化するということを通して、日本語の使い方を調整している、すなわち振仮名がいわば「調整弁」として機能しているということになれば、それは借用という枠組みをはるかに超えていることになる。漢語を借用することによって、和語の文字化がどのようになっていったか、という「和語の文字化の史的変遷」はこれまであまり話題になっていないテーマではないだろうか。

先に引用した中に、漢字列「准備」に振仮名「ようゐ」を施した例がある。これは「書き手」側からいえば、漢語「ヨウイ(用意)」の文字化にあたって、もっとも自然な漢字列「用意」ではなく、漢語「ジュンビ」に使う漢字列「准備」を使った例ということになる。こうした例は「後裔(しそん)」(20丁裏)「荘客(ひやくせう)」(22丁表)「撃剣(けんじゅつ)」(22丁表)「令(げぢ)」(28丁表)「支党(どうるい)」(28丁裏)など、少なくない。

「用意」と「准備」とのケースについては今野真二(2005)で詳しく述べたが、早くから日本語の語彙体系内に借用されていた「ヨウイ」の文字化に、「ヨウイ」におくれて借用されるに至った「ジュンビ」にあてる漢字列を使ったと思われる。漢語「ジュンビ(準備・准備)」は『水滸伝』や『三国志演義』において一定数使われており、(『水滸伝』よりは『三国志演義』のほうが文言的であることが指摘されているが、そうしたことを措けば)「白話的=近代中国語的」な語とみることは可能であろう。そして、滝沢馬琴を初めとして読本作者たちが、そうした近代中国語=非古典中国語の使用に興味をもったことはすでに指摘されてきている。

「ヨウイ」という漢語をもっとも自然な漢字列「用意」ではなく「ジュンビ」に使う漢字列「準備・准備」によって文字化するということは、意図的な文字列選択であることになる。通常は、「書き手」がどのような意図をもって当該漢字列を選択したかということは、選択された漢字列からはわからない。そもそも特別な「意図」があったかどうかもわからない。しかし、この場合は、もっとも自然な漢字列を選択していないという点において意図的であることだけははっきりしている。

このことを「読み手」の立場から説明すると、漢字列「準備・准備」を「ヨウイ」と読ませた、ということになる。「ヨウイ」と読ませたいならば、漢字列「用意」を使えばいいことになるが、そうではないので、「書き手」は漢字列「準備・准備」を使用したかったということだけははっきりしている。「書き手」側からみても「読み手」側からみても、「準備・准備」という漢字列を使いたかったということは一致しており、そのことは動かないといってよいだろう。

これを「文学表現」と呼ぶのであれば、語の文字化にあたって、いかなる単漢字、いかなる漢字列を選択するかということは「表現」の一部を担うといってよいことになる。この場合でいえば、「ヨウイ」という漢語は「用意」と文字化することがもっとも自然、すなわち標準的である、ということが明白であり、その「標準的な文字化」を一方において、何らかの「意図」の存在を確認し、それをもって「表現」とみなすという手順があるのであって、そうした検証なしに、現代日本語母語話者の目に特殊にみえる文字化を、そうした内省だけをたよりに特殊であるとみなすことはできない。

また、「書き手」の「表現」の中で振仮名をとらえるのであれば、「書き手」がどのような語彙を使用して(少なくとも)当該テキストをかたちづくっているか、ということについての目配りも必要になる。

振仮名について考えるためは、振仮名が施されている漢字列と振仮名として施されている語との関係、両者の結びつきを観察する必要がある。両者の関係、結びつきは観察しているテキストが成った共時態及び、その共時態内の「文字社会」を視野に入れながら考察する必要があると考える。

参考文献

今野真二 2005 「明治の中の近世-「準備」と「用意」とをめぐって-」(和泉書院『国語語彙史の研究』24)

多賀糸絵美 2012 「草双紙の漢語語彙-層別化の試み-」(和泉書院『国語語彙史の研究』31)

Konno Shinji, trans. Chris Lowy

Translator’s introduction

With this installment we enter the second half of our series on the architecture of written Japanese. Konno’s contributions have provided historical context and textual proof for much of the broader claims I make. Together, our essays provide a three-dimensional view of how the architecture of written Japanese developed and how and why those working within it make use of its features to a variety of ends, from aesthetic experimentation to radical political claims. This installment introduces perhaps the most important – and most misunderstood – characteristic of the Japanese writing system: furigana.

Furigana (振仮名) are intertextual glosses attached to the characters of the base text. They usually appear centered and just above a character or character-string in horizontally oriented texts and to the right in vertically oriented texts.

| Without furigana | With furigana | |

| Horizontal | 先生 | 先生 |

| Vertical | 先生 | 先生 |

The characters of the base text are usually Sinographs, though not always; furigana are usually used to represent pronunciation, though not always. It is the space between usually and always that Konno and I are largely interested in. That is, if furigana were always used to indicate conventional pronunciations, we would describe them as simple reading tools. Anyone who has read literature written in Japanese, from the oldest texts to today, knows that simply isn’t the case. The situation is further exacerbated when we realize it is precisely those working in a literary context that deploy furigana as a tool for expression in almost any conceivable fashion. But I’m getting ahead of myself – this point will become obvious throughout the rest of the series.

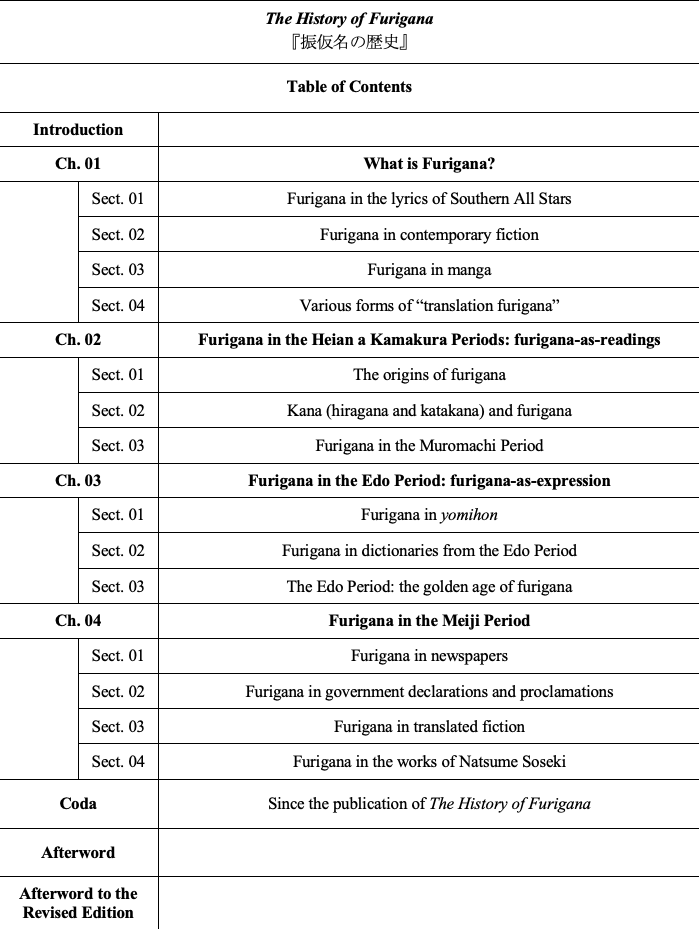

In lieu of an original essay I am presenting an excerpt from Konno’s important book, The History of Furigana (振仮名の歴史). Despite the critical role furigana plays within the architecture of written Japanese, this was the first examination of furigana in any language and indeed an inspiration for my own work. The History of Furigana was first published in 2009 by Shūeisha and was revised and republished in 2020 as part of Iwanami’s Gendai Bunko series, the version my translation follows. This partial translation will be split into three parts: Konno’s introduction to the book, which follows this introduction, and parts one and two of the opening chapter. Konno’s introduction presents his thoughts on how to approach the history of furigana and what methodologies might be useful in its pursuit. It also presents the larger scope of his text. Part One of Chapter One begins with a basic question: what is furigana? Konno grapples with this question by beginning from an unlikely spot: the furigana contained in the lyric sheets of legendary Japanese rock band Southern All Stars. Why should a lyric sheet, meant to record the spoken (sung) word, necessitate furigana, let alone irregular usages of it? Part Two of Chapter One moves to an examination of furigana in contemporary literature. The main texts discussed are Nakagami Kenji’s The Sea of Withered Tress (Karekinada, 1977), О̄e Kenzaburо̄’s The Game of Contemporaneity (Dо̄jidai geemu 1979), Murakami Ryū’s Coin Locker Babies (Koinrokkā beibīzu,1980), Inoue Hisashi’s Kirikirijin (1981), and Maruya Saiichi’s Kimigayo – Sing it in Falsetto! (Uragoe de utae kimigayo, 1982). All texts except for Murakami’s remain untranslated into English. I have made this claim elsewhere, but there seems to be a correlation between orthographical complexity and the likelihood of a text being translated into English. While my contributions will be translations, Konno has prepared three new essays on the topic of furigana: “The Furigana of the Edo Period,” “The Furigana of the Meiji Period,” and “The Potentiality of Furigana.” These essays, appearing for the first time, are meant to be additions to content contained in The History of Furigana.

I have also included a translation of the table of contents to Konno’s book. It is my sincere hope that readers will find these excerpts interesting and that a full translation into English of The History of Furigana can be soon completed. A final note: I have, with Konno’s blessing, conservatively altered some sections to make them more easily understandable for an English readership or otherwise match English conventions. I have decided to leave the term furigana untranslated. Footnotes in brackets are mine.

Introduction

Do snowmen have a history?

In the title of this book, The History of Furigana, the preposition “of” establishes a relationship between furigana and history. I would like to begin this text with an explanation of my thoughts on both terms, a discussion which will doubly serve as an introduction to the rest of the book. Let’s start by discussing the idea of history, a concept which brings with it at least four assumptions.

If we search online for the history of some topic, for example, the history of whaling, basketball, the Olympics, wine, Arima hot springs, or sewer systems, we quickly find articles and websites detailing how it began at a certain time in the past and has either continued to the present day or ceased to exist at some time before. In other words, the first assumption we have about history is that a given object or matter, what we can call a topic, must have existed for a duration of a certain length and continued for some time; a temporal continuation of an appropriate amount is key. If a snowman I built from snow that fell yesterday melts away without a trace in today’s clear skies, it is unlikely I would speak of that snowman’s history. While it wouldn’t be impossible, the reason I, and presumably you, too, would hesitate to do so is due to its temporal duration being too short. Some time ago a 14-year-old Olympic Gold medalist attracted media attention when she proclaimed, “This is the happiest I’ve been in my entire life.” The cause of this attention was likely the fact that the temporal duration of 14 years seemed incongruous with the image associated with an “entire life.” This is like the way highschoolers talking about “the good old days” rings unnatural to an adult’s ears. A topic must possess an appropriate temporal condition for it to have a history.

It is also important that a topic be categorizable: for example, basketball is just one game where balls are used and the Arima hot springs are just one hot spring among many. That is, though we can speak of the important Tone River’s long history we would likely be met with raised eyebrows were we to discuss the history of rivers in general. The river, despite being a single topic, is too large to stand alone as a useful category. The third condition that must be present when speaking of history is change. We cannot speak of the history of a topic that lacks change and movement. The fourth condition is less of a condition than an unavoidable question: from what perspective are we speaking of a given topic’s history? That is, if Team A is playing Team B in a sports match, do we talk about the game from the perspective of Team A, Team B, or the audience?

In brief, then, to live up to the title of a book called The History of Furigana, there (i) must be something that can be categorized as furigana, (ii) there must exist somewhere a beginning and origin story of furigana, and (iii) since furigana are still used today there must have been (iv) some observable changes that occurred from their origins to the present day. Even if someone knows what furigana is, ask them its origins or the changes that have occurred in its usage, and they are likely to draw a blank. The goal of this book is to sketch a history of furigana that answers these questions to the extent possible. I say to the extent possible because my intention is to tackle head on and in a responsible manner the question of furigana without relying on embellishments or vague information of which there is no shortage of. With this in mind, let’s take a closer look at furigana.

Readings and furigana

Directions: write the readings of the underlined Sinographs in hiragana.

事実を歪曲して報告している。

古い資料を廃棄する。

Don’t worry, this isn’t a pop quiz. The correct answers are わいきょく (waikyoku; to distort [something]) and はいき (haiki; to dispose of [something]). If you’ve studied in Japan, you likely have experience with similar questions on exams that are designed to test one’s ability to correctly read (i.e., pronounce) Sinographs. The question asks one to provide the reading(yomi) in hiragana, a phrase that is roughly interchangeable with “attach furigana to the Sinographs.” So, is a readingthe same thing as furigana? You might think so: if the exam question were rephrased as “attach furigana to the underlined Sinographs”the test takers wouldn’t bat an eye and the correct answers would be the same. In this case, then, we can say that there is no sizable difference between a readingand furigana by someone else.

However, when we say “reading”we are generally talking about the act of pronouncing a Sinograph that has already been written. When an exam asks for a Sinograph’s reading, we (usually) do not know who wrote the character in question. The reading subject in this case is not the writer (kakite) of the Sinograph but its reader (yomite), an important distinction when considering written Japanese. Reading a particular character, then, means reading something that has already been written. We can, of course, read something that we ourselves wrote, but the general implication is that we are reading something written by someone else. In other words, the act of reading, and producing a reading,is associated with the role and perspective of the reader, something I mentioned earlier.

Are furigana used in diaries?

Though it’s less common these days to keep handwritten journals, we can assume that, however few, some people still use them because stationery stores still carry them. In this section there are two things I would like to consider. The first is whether people use furigana in handwritten diaries they have absolutely no intention of showing to someone else. If one has no intention of sharing their diary with someone else then the writer is the writer and, at the same time, the reader. When the chance of someone else reading it is nonexistent there is no need to attach furigana for someone else’s benefit. We would not expect furigana to show up in a diary that only the writer intends to read. The point here isn’t the diary but the fact that only the writer will read it: at the end of the day, the act of attaching furigana assumes the existence of a reader different from oneself.

How our understanding of attaching furigana changes when considered from the perspective of the writer is the second thing I will consider. We can imagine the order in which things happen: first, the writer of a text chooses a combination of words to combine in order to create sentences. The next thing they think about is whether to write those words in hiragana, katakana, or, if appropriate, Sinographs. Perhaps they want to use Sinographs but its reading is difficult for the imagined audience, or maybe they want to write in Sinographs but use them in non-conventional ways. It’s at this stage a writer might attach furigana.

The handwritten manuscript of No Longer Human

Let’s imagine this order in concrete terms. Dazai Osamu’s No Longer Human (Ningen shikkaku, 1948) contains the following line:

自分は、それを堀木ごとき者に指摘せられ、屈辱に似た苦さを感ずると共に、…… (68; 126)[1]

It caused me a bitterness akin to shame to have this pointed out by someone like [gotoki] Horiki[, …].[2]

Looking at Dazai’s handwritten manuscript we see this section was initially written as 堀木如き, with Dazai erasing 如 and replacing it with the hiragana ごと (goto). Since Dazai replaced 如き with ごとき we can say there was a change at the orthographical level, not at the lexical one: the word gotoki was consistent throughout these changes. Dazai could have attached furigana to 如き but chose not to.

In the same line of the handwritten manuscript we see 屈辱に似た痛み□□苦みを感ずると共に, where □□ indicates the existence of two characters in two separate squares that are unreadable from the facsimile. Here we see that Dazai erased 痛み□□ and changed 苦み (nigami) to 苦さ (nigasa), transforming his initial sentence into the published version cited above. While nigasa and nigami, both meaning bitterness, are etymologically and denotatively similar each other, they are nevertheless different enough for Dazai to switch from one to the other. Furigana are left on 苦さ, but it is unclear if he attached these furigana when he initially wrote 苦み or if he first wrote 苦み and attached them to create 苦さ when changing vocabulary.

The first installment of No Longer Human was published in the June 1948 issue of Tenbō. Looking over Dazai’s manuscript we see that furigana are used only sparingly. It is likely that furigana were attached to 苦さ so as to avoid the Sinograph being misread as kurushisa [troubles; suffering]. Contemporary convention dictates kurishisha written with a Sinograph should be 苦しさ whereas nigasa becomes 苦さ. That is, the conventionalized use of hiragana (苦しさ / 苦さ) that trail a Sinograph, called okurigana, can differentiate between otherwise ambiguous readings. When these conventions were not well established it was at times difficult for the reader to differentiate between genuinely possible readings.

Elsewhere in No Longer Human are the following lines.

どこをどう彷徨まわつてたんだい (157; 297)

Where have you been wandering, and what have you done? *

さうして自分たちは、やがて結婚して、それに依つて得た歓楽は、必ずしも大きくはありませんでしたが、その後に来た悲哀は、凄惨と言つても足りないくらゐ、実に想像を絶して、大きくやつて来ました。(164; 307-8)

Not long afterwards we were married. The joy I obtained as a result of this action was not necessarily great or savage, but the suffering which ensued was staggering—so far surpassing what I had imagined that even describing it as “horrendous” would not quite cover it.

In the first example, urotsukimawatte (the conjunctive form of the verb urotsukimawaru, “to wander”), has furigana attached to it. This is likely because Dazai deemed this reading difficult for his imagined reader – indeed, under the entry for urotsukimawaru in the Nihongo kokogo daijiten three out of four citations of the term are written in hiragana. The only one to use 彷徨, typically read hо̄kо̄, is from a 1909 work by Morita Sо̄hei. In the second example, Dazai chose to write yorokobi (joy) and kanashimi (suffering) not in the conventional 喜び or 悲しみ but in two two-character Sinograph strings: 歓楽 and 悲哀. Were Dazai to simply leave these character-strings as is, there is a high likelihood the reader would read them in their conventional readings of kanraku and hiai, respectively. Dazai attached furigana here to indicate the marked reading of these Sinographs. The writer attached furigana to convey to the reader a desired reading, something needed given his irregular orthographical choices. This is one contribution of furigana. Understanding this allows us to discuss furigana from the perspectives of the reader and the writer. At the very least, it should now be clear that furigana can be more than simple pronunciation guides.

A journey into the history of furigana

Each episode of a serial drama ends with a preview of the next episode. If it’s too long there’s no need to watch the actual episode, but if it’s too short it’s hard to get a sense of what it’ll be about. These days there seem to be no shortage of offbeat previews that drag on and confuse the viewer. Don’t worry, all I’ll do in the rest of the Introduction is describe the book’s structure.

I wrote this book as a guide to what might be called a tour into the history of furigana. I wrote it with the intention of me serving as your guide. Tour guides provide us with concrete explanations of various kinds. I wanted furigana from various periods of history to come to life for the reader by using numerous visual examples. Tour guides, on the other hand, don’t generally rattle off their opinions on things. In fact, my editor urged me to provide more of my own personal thoughts. It goes without saying that I have many opinions about this topic, and I’ve written some of them, of course, but taking the text as a whole, it’s fair to say I’ve been reserved in my commentary. A nice view is best enjoyed in focused silence. Precisely because furigana is something I find interesting I want the reader to take their time and experience it for themselves. It’s with this mindset I’d like to start our journey deep into the history of furigana. To that end, it’s important to recognize that the history of furigana is contained within the larger category of the history of the Japanese language. A journey into the history of furigana is also a journey into the history of Japanese. I will sometimes talk about how the Japanese language was at a certain point in history or discuss the cultural context of a given period. You can think of these necessary detours as optional tours and excursions along our journey.

All this talk of history might lead you to assume our journey will begin with a discussion of the origins of furigana and continue chronologically to the present day. Chapter One, however, begins with a discussion of what furigana is and, citing numerous examples from the contemporary period, establishes guidelines for thinking about how to approach furigana. It is my hope that considering the varied usages of furigana today will serve as a warm-up of sorts. Chapter Two looks at furigana from the Heian (794 – 1185) to Muromachi Periods (1336 – 1573), Chapter Three focuses on the furigana of the Edo Period (1603 – 1868), and Chapter Four examines the furigana of the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912). Chapter Two onwards proceeds in chronological order.

I have adjusted the orthography of the sources cited on our tour in the following ways: hiragana and katakana have been adjusted to conform to contemporary spelling conventions while Sinographs follow the form of the source text.[3] If there were only small differences between the form of a Sinograph in the source text and those in contemporary use, and if I felt it would not alter its meaning, etc., then I have occasionally replaced those Sinographs with their contemporary equivalents. For example, I replaced 者 with 者 and 來 with 来 in the quotes from No Longer Human.

It is my belief that furigana originated as readings before also coming to be used as forms of expression. The function of furigana has expanded. Within this expansion of furigana’s functions lies the borrowing of Sinographs that resulted from continuous interactions between the Japanese language and the Chinese language. This is a complicated topic that I hope I’ve done justice to.

Talk of history conjures images of the past, present, and future. One reason is because the present serves as a point of connection between the past and the future. The present also allows us to enjoy the past and to pass it on to the future. A journey into the history of furigana, however, isn’t about appreciating furigana as some forgotten antique of the past. Rather, I want this to be a voyage that enables free passage between the present and the past – isn’t that one of the true joys of traveling anyway?

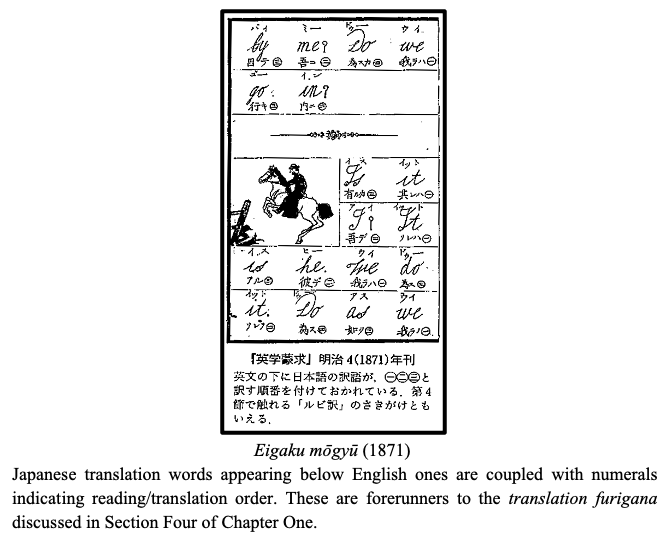

The Japanese translation words appearing below the English sentences appear with numerals 1-4 to indicate the correct reading order. We can consider these to be forerunners of the translation furigana discussed in Section Four.

[1] [The page numbers in parentheses refer to the 1948 paperback edition of Dazai’s Ningen shikkaku published by Tsukuma shobо̄ less than one month after the author’s suicide; the second refers to an annotated facsimile of Dazai’s handwritten manuscript, Chokuhitsu de yomu Ningen shikkaku, 2008, Shūeisha shinsho visual-ban.]

[2] [I have relied on Donald Keene’s translation of No Longer Human whenever possible. Selections followed with an asterisk indicate my own translation.]

[3] [As seen in the Dazai quotes, I have on occasion left source texts in the prewar orthography if those are the most readily available to me.]