標題「文字の方向」には2つの意味合いがある。1つは「文字の向き」ということで、このことについては案外と論じられてきていないように思われるので、少し整理してみたい。もう1つは「書字方向」である。

[文字の向き]

屋名池誠(2003)は「普通、一つ一つの文字(単字)は、回転させてもちがう文字にはならない。文字をもたなかったネイティブ・アメリカンのために宣教師が創案したというエバンス音節文字という文字や、われわれの身近でいえば速記のような、人為的・意図的に作られた文字体系をのぞくと、同じ図形を向きによって異なる文字に当てるというのは、文字の構成原理にはなっていないのである。だから、文字は回転させても同じ文字であることには変わりないのだが、しかし普通、単字には「この向きから見る」という一定の方向性がある。いわば正立像である」(5-6p)と述べている。

重力のはたらく方向を「垂直・鉛直」と呼ぶが、生物としてのヒトは「鉛直」すなわち水平面と垂直な方向に立っていることになる。そのように立っているヒトの目がとらえた像「正立(upright)」像ということになる。

ピアノには、コンサートなどで使う、大きなgrand pianoと家庭などで使う、小ぶりなupright pianoがあるが、grandpianoの弦が水平方向に張られているのに対して、upright pianoは弦が鉛直(垂直)方向に張られている。その「鉛直(垂直)」がupright=正立ということになる。

「二」という漢字であれば、短い横棒が上、長い横棒が下になっている像が「正立像」ということになる。自身の身体の向きは変えずに、この「二」を右に90度回転させると、左側に長い縦棒、右側に短い縦棒が並んでいる「二」という形になるが、そうなった時に、「異なる文字」になるわけではなく、あいかわらず文字としては「二」で、正立していないと認識する(註1)。

屋名池誠(2003)が述べるように、「横書き」「縦書き」は、文字とそれが記されている面との関係によって規定されているのではなく、並んでいる文字どうしの関係がどのようであるかによって決まる。方向には「水平方向」と「垂直方向」とがあって、文字の正立像に対して、水平方向に文字が並んでいるものが「横書き」、文字の正立像に対して垂直方向に文字が並んでいるものが「縦書き」と呼ばれる。

ヒトが水平面に垂直な方向に立つことによって、「上下」「左右」が意識されるようになったはず(註2)で、上には「天」があり下には「地」があるという「世界観」も自然に獲得されていったと思われる。天地を結ぶ線が垂直線で、足下の地の方向に水平線がのびる。これを文字にあてはめれば、縦線と横線ということになる。「左右」が意識されれば、左右対象ということも意識されると思われる。

[鏡文字(反文・反書)]

「鏡文字」は鏡にうつったように、左右が逆になっている文字で、現在いうところの「反転文字」のことを指す。

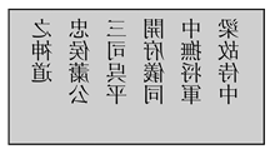

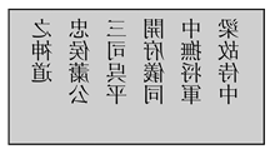

「呉平忠侯蕭景神道石柱題字」と呼称されている、中国の南朝、梁の時代に、忠と諡された蕭景の墓の神道に建つ石柱の題字がある。この題字は公開されている拓本の画像(註3)などで確認することができる。石川九楊(1996)は、この題字について、「五二三年以後。梁の蕭景(武帝の従弟)の墓前にある二本の柱の額の題字。一方は、二三字が、反文で右から左に六行書かれている。もう一方の柱は現存しないが、額の題字は互いにシンメトリーになり、正文で左から右に書かれていたであろうと推測されている」(9p)と述べている。

ところで、文字あるいは語を異なる方向からも読めるようにしたグラフィカルな文字を「アンビグラム(ambigram)」と呼ぶことがあるが、「鏡文字(Mirror Ambigram)」は「アンビグラム」の一つといってよい(註4)。回転させた「Rotational Ambigram」や語が鎖のように繰り返し繋がっている、 アメリカのSun Microsystemsのロゴデザインのような「Chain Ambigram」もある。日清のアルファベット表記「NISSIN」はそのまま「Rotational Ambigram」になっており、さらに「回文」でもある。西尾維新のローマ字表記「NISIOISIN」は「O」を中心に180度回転させた「Rotational Ambigram」になっており、これも「回文」になっている。日本国有鉄道のロゴも回転させても同じ形になるようにデザインされていると思われる。スゥエーデンのポップグループ「ABBA」のロゴも左右対象になっている。

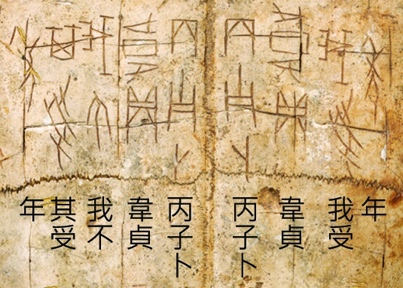

台北の中央研究院に「丙子卜/韋貞/我受/年」(丙子卜す。韋、貞(と)う。我、年(みのり)を受けんか」と右側に左から右に向かって記され、左側には「丙子卜/韋貞/我不/其受年」(丙子卜す。韋、貞う。我、其れ、年を受けざるか)と右から左に向かって記されている甲骨文が蔵されている。石川九楊(1996)は8ページ、18-19ページにこの甲骨文の写真を掲げているが、カバーの袖にもカラー写真が使われている(註5)。

亀甲の中央線(天里路)の右側には、「左縦書き」で肯定文、左側には、「右縦書き+鏡文字」で否定文が刻されており、「左右対象」がつよく意識されていることがわかる。藤枝晃(1971)は「亀の甲だと、中心線の左右に、同一のことを、「禍アリヤ」「禍ナキヤ」と二つの形式で問いかける」(45p)と述べており、この左右対象は神への問いかけの定まった形式であったことがわかる。

漢字Xを反転して「鏡文字」Yにした場合、目でとらえている形は、大きく異なる。それでもXとYとが同じ文字であると認められるのであれば、それはXに「反転」という操作をすることによってYになっているということが認識できている必要がある。そしてまた、そうであるのならば、漢字は目、すなわち視覚でとらえている具体的な形を、いわば超えて認識されている(註6)ことになるが、それは甲骨文字が使われていた時期に限られた認識であるのか、中国の後の時代でも潜在的にはそうであるのか。さらには時空の異なる日本ではどうなのか。こうしたことについては、今後考えてみたい。

[書字方向]

「あさがお」という平仮名4字で文字化される語を例としてみよう。「あ」に続く「さ」が水平方向に置かれていれば「横書き」、垂直方向に置かれていれば「縦書き」ということになる。左から右へ「あさがお」のように文字が続き、下へ行移りする場合が「左横書き」、右から左へ「おがさあ」のように文字が続き、下へ行移りする場合が「右横書き」になる。「縦書き」には右から左へ行移りがする「右縦書き」と、左から右へ行移りがする「左縦書き」とがあることになる。

「正立」した文字を左に90度倒したり、右に90度倒したりすることができる。このように「正立」した文字を横に倒すことを「横転」と呼ぶことにする。「あさがお」は(左90度の)「横転縦書き」ということになる。「行移り」という表現を使ったが、書字方向には「行」という概念も関わっている。屋名池誠(2003)は「日本における横書きは--右横書きも、左横書きも--横書きする外国語の文字との関わりから生じたもの」(22p)と指摘している。

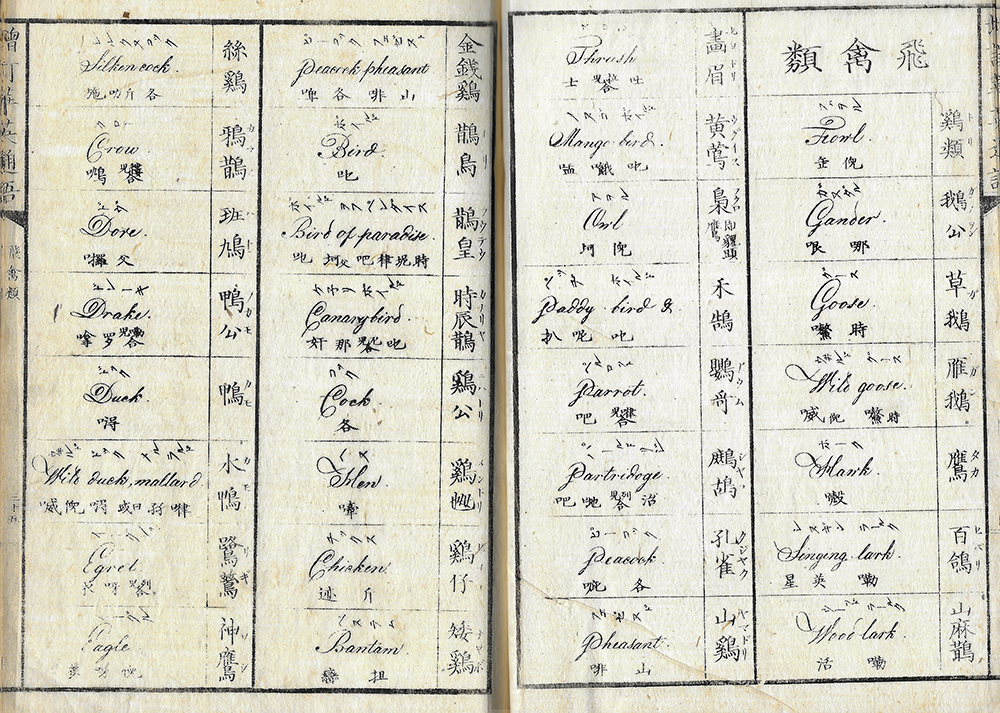

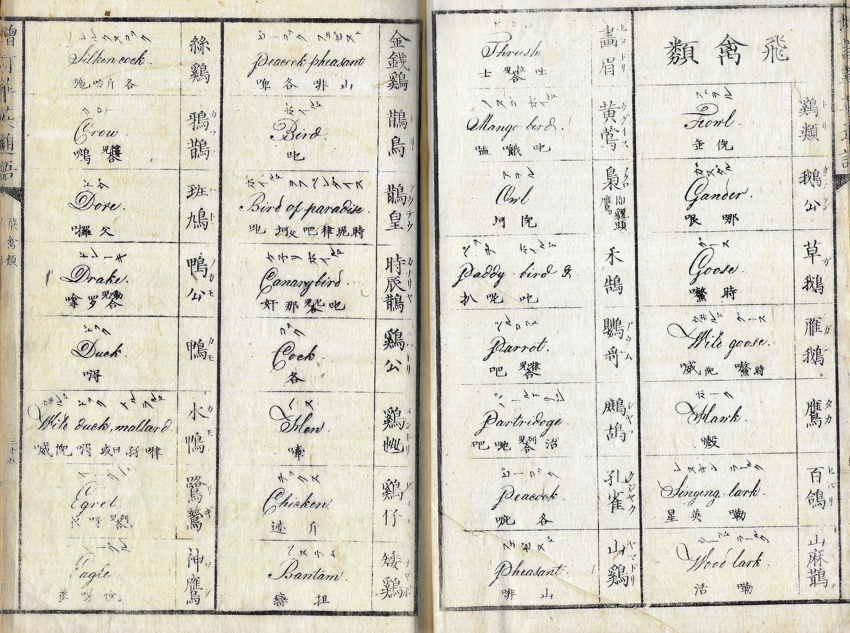

図1(末尾)は福澤諭吉が清の子卿の『華英通語』に日本語を加えて翻刻した初刷りの2冊本を1冊にまとめた『増訂華英通語』である(註7)。万延元(1860)年に出版されている。

英単語を46に分類し、1つの単語ごとに筆記体で英語を示し、その上に「横転縦書き」の片仮名で発音を示し、下には「左横書き」の漢字でやはり発音を示し、右には英単語に対応する中国語を漢字で「縦書き」にし、その漢字列のさらに右に片仮名で、対応する日本語を「縦書き」で示している。片仮名で文字化されているところが、福澤諭吉が増訂した部分にあたる。「飛禽類」という分類は、漢字で「右横書き」されている。

したがって、このテキストの版面においては、「右横書き」「左横書き」「横転縦書き」「右縦書き」が「同居」していることになる。それは、改めていうまでもなく、この版面が、中国語、日本語、英語の出会う「場」であるからといってよい。

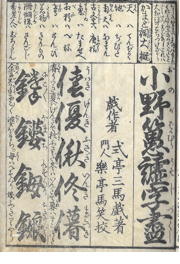

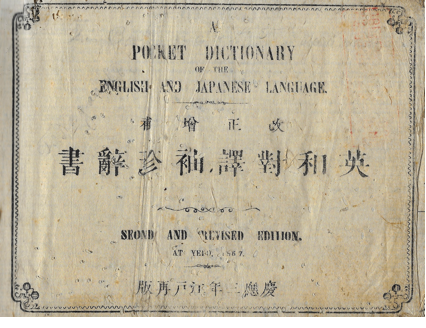

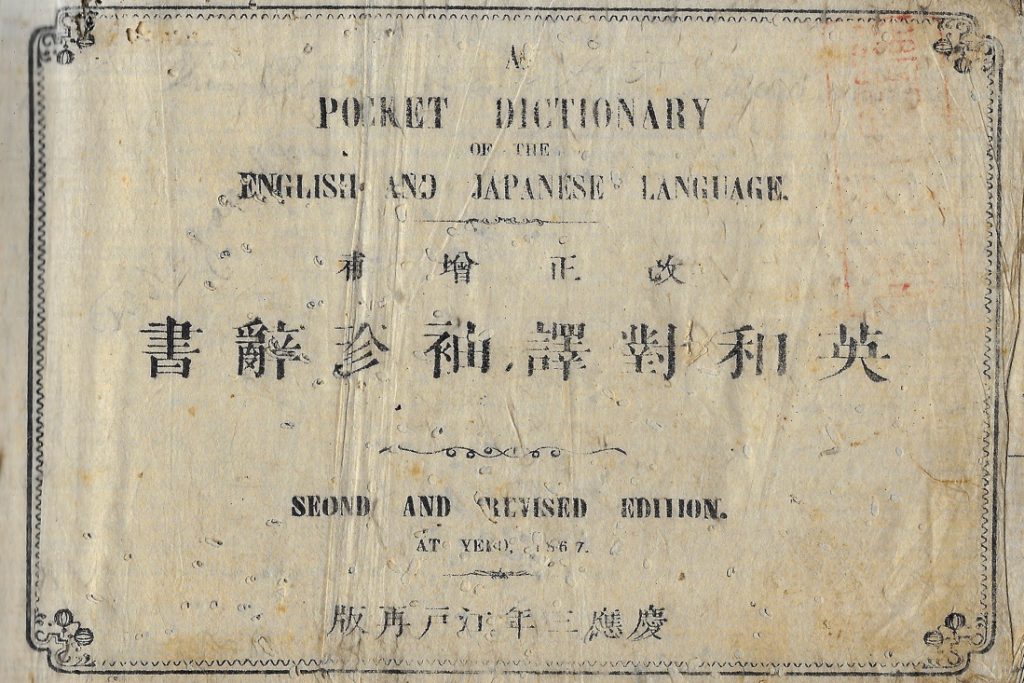

図2は文久2(1862)年に出版された、最初の官版英和辞書『英和対訳袖珍辞書』の再版2刷にあたる「慶應三年江戸再版」の表紙見返しである。慶應3年は西暦1867年にあたる。タイトルである「A/POCKET DICTIONARY/OF THE/ENGLISH AND JAPANESE LANGUAGE」が「左横書き」され、「改正増補/英和対譯袖珍辞書」が「右横書き」されている。「慶應三年江戸再版」も同様。辞書の「本文」は、見出しとなる英語が「左横書き」され、語釈は「横転縦書き」されている。

「左横書き」をいわば「知ってしまっている」現代日本語母語話者にとっては、英語に合わせて語釈の日本語も「左横書き」しないのはなぜかと、むしろ疑問に思うかもしれない。しかしそれだけ日本語は「縦書き」という「心性」がつよかったということであろう。

屋名池誠(2003)は、「押しも押されもせぬ日本語の自立した左横書き」の例として、明治4(1871)年10月に出版されている英和辞典、『浅解英和辞林』を「最初の例」(61p)として指摘している。資料を博捜していくと、これよりも早い例がみつかる可能性はあろうが、およそこの頃に日本語の「左横書き」が行なわれ始めたと考えてよいだろう。日本語はこの頃から「右縦書き」と「左横書き」という2つの書字方向を獲得したといってよい。

[行の意識]

今野真二(2021)の第2章第1節の2「書記における「行」意識」において、「粘葉装にせよ綴葉装にせよ、一枚一枚の料紙を単位として書物が作り上げられた時に、その一枚の料紙は書物の物理的な構成単位であると同時に、心理的な、つまりは書記の一つの単位ともなったと考えられる。「丁」が意識されればそれを構成する「行」に意識が向くのはそう遠いことではなかったと予測する。定家・為家の時代にはすでに「行」が書記に際して意識されていたと考えられる」(208p)と述べた。

これは冊子体のテキストを考えてのことであるが、巻子本であっても、紙の縦の長さは決まっており、紙の上端から書き始め、紙の下端に至れば、次の「行」に続けるということはいわば必然で、そうした書記行為の中で「行」の意識が醸成されていったと推測する。

言語は「線条性」をもっており、言説が終わらない限りは、どこまでも続いていく。そのどこまでも続いていく言語をさながらに文字化するためには、縦書きであれば、縦にどこまでも続いていく紙を用意しなければならないし、横書きであれば、横にどこまでも続いていく紙を用意しなければならない。いうまでもなく、そのような紙はない。言語は続いているが、文字は次の「行」に移るということは、当初は、「必然」で、それは続いている言語を分けて文字化せざるをえないということであったと思われる。その場合は、「行」が何らかの言語単位として独立していたということではない。しかし、1行でまとまりをつけようとする「心性」は「行」を独立したものとしてとらえていることを思わせる。

承平5(935)年頃に成ったと推測されている、紀貫之『土左日記』自筆本は、藤原定家によって文暦2(1235)年に、定家の息である為家によって嘉禎2(1236)年に、松木宗綱によって延徳2(1490)年に、三条西実隆によって明応元(1492)年に書写されている。これらの根幹写本及び、根幹写本につながる本によって、紀貫之自筆本がどのようなものであったかがかなりな程度までわかっている。

為家による写本は、大阪青山歴史文学博物館に蔵されている。「青谿書屋本」と呼ばれるテキストは、この為家写本を江戸時代に書写したもので、為家写本が出現するまでは、為家写本に準じるテキストとして扱われてきた。

ここでも、その「青谿書屋本」を使うが、「青谿書屋本」には行末に文字を横に並べるようにして記されている箇所がある。例えば、1月10日の条は「十日けふはこのなはのとまりにとまりぬ」とあって、次の行は「十一日あかつきにふねをいたしてむろ/つをおふひとみなまたねたれは」とある。「とまりぬ」の「りぬ」は「ま」字の左側に記されているが、これは貫之自筆本では、十日の条が1行で記されていたために、「青谿書屋本」(すなわち為家本かどうかは、為家本を確認しなければわからないので、ここでは「青谿書屋本」と表現しておく)も1行で記すために行末を少しつめて書いたものと推測できる。この場合は、十日が1行で、次の行が十一日から、ということが「絶対」にちかく、「りぬ」が1行に収まらないから、次の行に「りぬ」を記して、その下から十一日の記事を始めるということはおよそ考えられないし、「りぬ」だけ記して、行を変えて、次の行を「十一日」から始めるということも考えにくい。しかし、言語が続いているということからすれば、原理的には「りぬ十一日~」と記してもいいことになるが、そのようにはなっていない。あるいは一月十八日の条中に「そのうたよめるもしみそもし/あまありなゝもしひとみなえあらて/わらふやうなり」というくだりがある。(/は改行位置)「みそもし」の「し」は「も」の左側に記されている。この場合は「みそもしあまりななもし」というひとかたまりの表現を「みそも/しあまりなゝもし」と記すことを避けているようにみえる。そうであれば、それは「みそもしあまりななもし」(三十文字あまり七文字)を「みそもし」「あまり」「ななもし」と分ける「心性」によるものではないか。ここでは語のまとまりが意識されていると思われる。

どこまでも切れ目なく続く言語に切れ目をいれて把握する、すなわち「分節」することは文字化することと表裏一体といってよい。切れ目を入れて、文字と対応させることが文字化においては重要で、「言語単位意識」、「分節意識」、「行の意識」の胚胎と書字方向はかかわる。

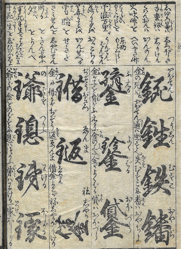

註1 これはもちろん「二」という字形をもつ漢字が存在しないということを前提としている。図3は文化3(1806)年に出版された『小野X譃字尽(おののばかむらうそじづくし)』(Xは「篁」の「皇」を「愚」に置き換えた字)というテキストで、手習いをする子供が漢字を覚えるための教科書として編まれたと思われる『小野篁歌字尽(おののたかむらうたじづくし)』というテキストを、式亭三馬がパロディ化したもの。左ページの三行目には「言偏×借」「言偏×返」「借金」が一字化され、さらに横にたおれている形の字、合計3つの創作漢字が並べられ、右にそれぞれ「ぢぞうぼさつ(地蔵菩薩)」「ゑんま(閻魔)」「ねじやか(寝釈迦)」と振仮名が施されている。左側には「金(かねへん)に借(かり)るがぢぞう返(なす)ゑんま借金(しやつきん)よこがねじやかなりけり」という和歌風のことばが置かれている。お金を借りる時はお地蔵さまのような顔で貸してくれるが、返すとなると閻魔さまのようにとりたてるということだろうか。「横に寝る」には「返済、支払、納入などをしないでいる。特に、借りたものを返さないでいる」(『日本国語大辞典』「横にねる」)という意味があるので、「借金」を横に倒した形をつくり、地蔵、閻魔に揃えて「寝釈迦」という振仮名を施したものと思われる。

註2 白川静(2012)は「掌(てのひら)の上に指示の点をつけて、掌の上を示し、「うえ」の意味を示す。下は掌を伏せ、その下に指示の点をつけて、掌の下を示す。のち指示の点は縦の線となってT・Tの形となり、さらにその傍らに点を加えて上・下の形になった」(348p)と述べている。

註3 例えば、東京大学が公開している関野貞拓本画像アーカイブで「梁故侍中/中撫将軍/開府儀同/三司呉平/忠侯蕭公/之神道」の23字を確認することができる。また、石川九楊編、書の宇宙1『天への問いかけ 甲骨文・金文』(1996年、二玄社)の9pにも写真が掲載されている。初唐楷書の古典的名品として知られる、褚遂良(596-658)の「雁塔聖教序」は、西安の大雁塔南門の龕の左側の、唐の太宗の「大唐三蔵聖教之序」(法帖では前半)、右側の、後の高宗となった皇太子李治の「大唐三蔵聖教序記」(法帖では後半)、二つの碑からなる。左側の「大唐三蔵聖教之序」は右から左に行が進む「右縦書き」、右側の「大唐三蔵聖教之序記」は左から右に行が進む「左縦書き」で記されている。つまり、二つの碑の文章は書字方向が左右対象になっている。これは「文字の向き」ではなく、「書字方向」についてのことであるが、中国の書字において、「左右対象」がはっきりとした概念として存在していることの証といってよい。

http://kande09.ioc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ap/takuhon/jpeg/images/0005_A.jpg

註4 Dan Brownの小説『Angels & Demons(天使と悪魔)』では「アンビグラム」が話題となっている。

註5 中央研究院歴史語言研究所が画像と翻字を公開している。

http://museum.sinica.edu.tw/_upload/image/library/large/861573e801dea2dd.jpg

註6 「秋」は「禾」が左、「火」が右に位置しているが、左右が入れ替わった「秌」が使われることがある。「秋」と「秌」とは異体字とみなされている。例えば、昭和26(1951)年から昭和28(1953)年にかけて雑誌『宝石』に連載された、横溝正史「悪魔が来たりて笛を吹く」に「椿秌子」という登場人物がいる。この人物は「秌子」と表示され「秋子」とは表示されない。その一方で、夏目漱石「それから」の登場人物「島田」は、漱石は自筆原稿に「嶌田」と書いているが、それは印刷されたテキストには反映されていない。漱石の「嶌田」はいわば無視されている。こうしたことについて、どのような「心性」がはたらいているのかを考えることは今後の課題であろう。

註7 関西大学が「関西大学東アジアデジタルアーカイブ」で全体の画像を公開している。

https://www.iiif.ku-orcas.kansai-u.ac.jp/books

参考文献

石川九楊 1996 『書の宇宙1 天への問いかけ 甲骨文・金文』(二玄社)

今野真二 2001 『仮名表記論攷』(清文堂)

白川静 2012 『常用字解 [第2版]』(平凡社)

藤枝晃 1971 『文字の文化史』(岩波書店、後1991年、岩波書店刊、同時代ライブラリー再収、1999年講談社学術文庫所収。引用は講談社学術文庫による)

屋名池誠 2003 『横書き登場-日本語表記の近代-』(岩波書店)

Note: for this installment I present an English translation of Konno’s piece. His contribution outlines the limited treatment of directionality in both Japanese and English language research. His essay also highlights the way interactions with other architectures of script can re-shape conceptions of directionality, a topic related to my discussion of typographical markers. With readability in mind, I have inserted images and added commentary where I thought necessary and omitted most of the longer footnotes included in the original. The latter will be of great interest to the more philologically inclined.

The subtitle of this installment – the orientation and direction of characters – refers to two things at once. First, it refers to the directional orientation of a given character, a topic that has, perhaps surprisingly, been little discussed. The second refers to the direction in which text is written.

The Directional Orientation of Characters

Yanaike Makoto, a Japanese linguist who has written extensively on the history of written Japanese, explains that,

It is usually the case that rotating individual characters will not transform them into different ones. With the exception of some artificial writing systems developed by, for example, the missionary James Evan to write hereto unrecorded Native American languages or, a bit closer to home, the various forms of shorthand (速記) used to write Japanese, the idea that changing the orientation of a character would result in the creation of new ones goes against the basic structural principles of written language. Put another way, we can say that a character remains the same even when rotated. However, there is usually a fixed directionality associated with individual characters, something we might call its upright image.

(Yanaike, 5-6)

It is the image captured from the eyes of humans that constitute this upright image (正立像). Since the directional pull of gravity is vertical and downward, humans, which stand vertical to the horizontal plane, create something of an X/Y axis. This sense of urprightness dictates how we see and understand the world. For example, recall that large pianos used at concerts and other events are called grand pianos, while pianos used at the home are called upright pianos; while the strings of a grand piano are strung horizontally, the strings of an upright piano are strung vertically. It is because of this vertical orientation that we think of it as upright.

The same principle is true of written language. In the case of the Sinograph meaning “two” 二, a short horizontal line sits atop a longer horizontal one, creating what we understand to be the upright image. If you do not change your orientation but rotate said Sinograph 90 degrees, the shape of the Sinograph will change such that a long vertical line is on the left-hand side while a shorter vertical one sits on its right-hand side. Nevertheless, the result is not a different Sinograph; rather, readers would understand it as being a tilted or rotated – i.e., not upright – version of the Sinograph we are all familiar with.

As Yanaike notes, horizontal writing/vertical writing is not determined by the relationship between characters and the surface upon which they are written; rather, directionality is determined by the relationship between the characters themselves. We can say there is a horizontal direction and a vertical direction, and if a character string is written horizontally relative to a character’s upright image it is horizontal writing; if a character string is written vertically relative to a character’s upright image, then it is vertical writing. Thus, (A word or a sequence of words that reads, letter for letter, the same backwards as forwards.a) below is an example of horizontal writing while (b) is an example of vertical writing.

Humans likely came to recognize the categories of up and down and left and right by standing vertically against the horizontal plane. From this realization it is not a stretch to imagine humans naturally acquiring a worldview that places the sky (天) above and the earth (地). The line connecting heaven and earth is a vertical one while a horizontal one shoots across the earth we stand upon. The principles of this heaven/earth divide, when applied to written language, gives rise to conceptions of verticality and horizontality. I suspect it was the same process that led to the emerge of a right/left classification.

Mirror Writing

Mirror writing refers to characters whose left/right orientation is flipped, thus appearing as if they are reflected in a mirror. This writing is also called reversed writing.

There was a grave erected during China’s Liang Dynasty (502-557) for a certain Xiaojing (蕭景), posthumously named Zhong (忠), that contains an inscription on stone tablet extolling the deeds of the deceased person.[1] This inscription can be seen in published rubbings and other places. The esteemed calligrapher and artist Ishikawa Kyūyō describes the inscription thus.

It was [created] sometime after the year 523, and there are inscriptions on the face of two columns standing in front of the tomb of Xiaojing of Liang, a cousin of Emperor Wu. One has 23 characters in six lines written from right to left in a mirrored hand. The other column is not extant, but it is assumed that the inscriptions are symmetrical with each other, and that it would have been written from left to right in the regular script.

(Ishikawa, 9)

Letters or words that can be read from different directions and orientations are called ambigrams, with the type of writing seen on the columns at Xiaojing’s tomb being mirror ambigrams, a subset of the former. Rotating characters give rise to rotational ambigrams, while chain ambigrams are when words are repeated and connect like a chain. The logo of Sun Microsystems is an example of a chain ambigram while Nissin Foods’ logo, written in Roman characters, is both an example of a rotational ambigram and a palindrome, a sequence of letters or words that reads the same backwards as forwards.

The Romanization of author Ishin Nishio’s name, which he fashions as NISIOISIN, becomes a rotational ambigram when rotated 180 degrees with the O at its center; it, too, also doubles as a palindrome. The logo for Japan National Railways (JNR) is also designed to have the same shape when rotated, and the logo of the Swedish pop group ABBA is designed to be symmetrical when read from either right-to-left or left-to-right.

Academia Sinica in Taipei has as part of its collection an oracle bone inscription that reads, from left-to-right on its right divide, 丙子卜/韋貞/我受/年 (“Crack-making [卜] in the year of the Fire Rat [丙子], Wei [韋] divined [貞] we will receive [我受] good harvest [年]”) and, read from right-to-left on its left divide, 丙子卜/韋貞/我不/其受/年 (“Crack-making in the year of the Fire Rat, Wei divined perhaps [其] we will not receive [我不受] good harvest”).[2]

Ishikawa includes a black and white image of this inscription in his book (8; 18-9) and a color photo appears on the jacket to the text. On the right divide of the tortoise shell is an affirmative sentence inscribed in left-originating vertical writing while on the left divide is a negative sentence inscribed in a hand best described as right-originating vertical writing in a mirrored script. This suggests a strong awareness of a left-right orientation. Fujieda Akira understands this to mean that on the tortoise shell “the same question is asked in two forms on either side of the center line: will we receive good harvest? and will we not receive good harvest?, which tells us this left/right text is the same question posed in two ways” (Fujieda, 45). This suggests that such a style was an established way of asking the gods a yes/no question.

If Sinograph X is flipped to create Mirror Sinograph Y, the eye will capture an image drastically different from one it is used to. Nevertheless, if X and Y are recognized as being the same character, then one intuitively understands that Mirror Sinograph Y is created by flipping Sinograph X. That being the case, then, we could say that Sinographs transcend their material form, understood at a level beyond their visual image. The question then becomes whether such an understanding was limited to the period in which oracle bones were used for divination or if said understanding still lay dormant in later periods of Chinese history. The same question can be applied to Japan.

The Direction of Writing

How is directionality determined? Let us take the character string あさがお (a-sa-ga-o, a morning glory), comprised of four hiragana, as an example. If the さ that follows あ is written horizontally then it is horizontal writing; if it is placed vertically then it is vertical writing. If the あさがお unfolds from left to right and the lines of the text transition downward then it is left-originating horizontal writing; if the おがさあ unfolds from right to left and the lines of the text transition downward the it is right-originating horizontal writing. Similarly, when the lines of text in vertical writing transition from right to left it is right-originating vertical writing; when the lines of text transition from left to right it becomes left-originating vertical writing.

One can tilt an upright character 90 degrees to the left or 90 degrees to the right. Tilting an upright character to the right results in what I call a right tilt. Above I mentioned a line transition; indeed, the concept of the line (行) is related to the direction of writing. Yanaike points out that for horizontal writing in Japan, “both right-originating horizontal writing and left-originating horizontal writing emerged through exposure to the letters of Western languages that were written horizontally” (Yanaike, 22).

The above image is from Fukuzawa Yukichi’s first published work, the Zōtei kaei tsūgo (増訂華英通語, 1860), itself an expanded and collected version of a two-volume Chinese-to-English dictionary of the same name compiled by Ziqing (子卿) of the Qing Dynasty. The English words are classified into 46 categories with each word written in cursive English. Above each English word is the Japanese pronunciation recorded in katakana with the text appearing in tilted vertical writing; below each English word are left-originating horizontal Sinographs that indicate (the Chinese) pronunciation. To the right of each English word is a Chinese translation of the term in vertical writing while even further to the right of that character string is, in vertical writing, the Japanese meaning of the term written in katakana. The katakana writing was Fukuzawa’s contribution to the compiled text. The classification header 飛禽類 (flying beasts) appears in horizontally-originating writing.

We could correctly say that the layout of this text is, variously, right-originating writing, left-originating writing, side-tilted vertical writing, and right-originating vertical writing. It perhaps need not be stated, but this is because this text is a point of intersection between the Chinese, Japanese, and English languages and the various architectures used to write the Roman alphabet, Sinographs used to write Chinese, and the combination of Sinographs and kana used to write Japanese.

The image below shows the inside page of a reprinting of Eiwa taiyaku shūchinsho (英和対訳袖珍辞書, 1862), the first government-sponsored English dictionary. This reprinting from the Edo period was published in the third year of Keio (1867). The English title of the book, A / POCKET DICTIONARY / OF THE / ENGLISH AND JAPANESE LANGUAGE, is printed in left-originating writing while the Japanese title is printed in right-originating writing, as is the publication information. As for the base text of the dictionary, the English headwords are written in left-originating writing while Japanese explanations appear in tilted vertical writing.

Speakers of modern Japanese who are familiar with left-originating writing might wonder why the Japanese portion of the dictionary is not written from left-to-right to match the English text. Though impossible to say, it is likely that vertical writing sat firmly at the core of the Japanese writing experience.

Yanaike cites the 1871 English-Japanese dictionary Senkai eiwa jirin (浅解英和辞林) as the first example of “left-originating writing that broke from the firmly established Japanese [text]” (Yanaike, 61). Though further research might reveal earlier examples, it is likely that left-originating writing in Japan began around this time. Though possible that an earlier example could be found through further research, it is safe to assume that Japanese-language left-originating horizontal writing began to be used around this time. Put another way, it was around this time that written Japanese acquired bidirectionality: right-originating vertical writing and left-originating horizontal writing.

Line Awareness

Elsewhere I have written that

[w]hen a text is created from individual sheets of paper, those single sheets constitute the physical building blocks of the manuscript, regardless of whether a text is in a butterfly (粘葉装) or pouch binding style (綴葉装). At the same time, it seems those individual sheets come together to create the manuscript, itself a single unit of measure. We can imagine that if the concept of a page or leaf (丁) becomes established then the concept of the line won’t be far behind. It is believed that the notion of the line was already established by the time of [the poets] Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241) and Fujiwara no Tameie (1198-1275).”

(Konno, 208)

I had texts of the pamphlet style (冊子体) in mind when I wrote that, but even in the case of rolled scrolls (巻子本) it was in a sense necessary that the height (vertical length) of the page was fixed. We can imagine that if we begin writing from the top edge of a page and land at the bottom edge of that page then a line consciousness would be cultivated throughout the act of writing.

Since languages possess linearity, we can say that a statement can continue ad infinitum so long as it does not come to an end. To write down a statement that continues forever one must prepare a piece of paper that goes on forever vertically if it is written vertically or one that goes on forever horizontally if it is written horizontally. Such a paper does not exist. Language marches on but from the very being it was inevitable that written language would have to shift from one line to another; there was no choice but to divide language into pieces and record them in some written language. This does not mean that the line existed as some independent linguistic unit. However, there is clearly a natural desire to view the end of a line as a natural place to end an utterance.

Though no longer extant, the textual history of Ki no Tsurayuki’s handwritten Tosa nikki, thought to have been compiled around 935, allows us to understand with relative certainty what it looked like: it was copied by Fujiwara no Teika in 1235, in 1236 by Teika’s son Tameie, by Matsuki Munetsuna in 1490, and Sanjōnishi Sanetaka in 1492. Tameie’s manuscript is housed in the Osaka Aoyama History & Literature Museum (大阪青山歴史文学博物館). The famed Seikei Manuscript (青谿書屋本), considered to be the authoritative version until Tameie’s copy was discovered in 1984, was in fact copied from Tameie’s sometime in the Edo period (1603-1868).

There are parts of the Seikei Manuscript where characters appear next to each other at the end of lines of text. For example, on the entry for the 10th day of the first month (15 February) reads 十日けふはこのなはのとまりにとまりぬ (“[Day 10:] Today they remained at this stopping-place, Nawa”), with the next line reading 十一日あかつきにふねをいたしてむろ/つをおふひとみなまたねたれは (“[Day 11:] The boat started at break of day and headed for Murotsu. They were all still half asleep […]”).[3] The final two hiragana of “[they] remained,” the りぬ of とまりぬ, are written to the left of the ま. The decision by the author of the Seikei Manuscript to keep these entries to one line by squeezing two hiragana together is likely attributed to the (unverified) fact that Ki no Tsurayuki’s handwritten manuscript had the entry for the 10th day in a single line. It is inconceivable that one would write the りぬ on the next line and start the entry for the 11th below it. Similarly, it is hard to imagine that one would start a new line after only writingりぬ. In principle, there should be no issue starting one entry immediatley after another (e.g., りぬ十一日). In practice, though, this does not seem to bethe case.

There is also a section from the entry on the 18th day of the first month that in part reads そのうたよめるもしみそもし/あまありなゝもしひとみなえあらて/わらふやうなり (“But, as his verse had seven-and-thirty syllables, the others could not help laughing”). The し of みそもし, “thirty syllables,” is written to the left of も. In this case, it seems as if the author is trying to avoid splitting the phrase みそもしあまりななもし, “thirty-and-seven syllables,” into みそも/しあまりなゝもし. Perhaps we can attribute this to a certain sensibility to divide the phrase into discreet chunks, namely みそもし, あまり, and ななもし. It seems apparent that a cohesion of words is understood by the writer.

The process of segmentation, the grasping of an endless language by inserting breaks into it, is inextricably linked to the process of writing. They are, in fact, two sides of the same coin. Inserting breaks into language and making it correspond to written language is crucial to the act of writing, and one origin of the resulting awareness of linguistic units, segmentation, and lines, lies in the directionality of written language.

Work Cited

Ishikawa Kyūyō, Sho no uchū 1 ‘Ten e no toikake: kōkotsubun kinbun’, Nigensha, 1996.

Konno Shinji, Kana hyōki ronkō, Seibundo, 2001.

Shirakawa Sizuka, Jōyō jikai, Heibonsha, 2012.

Fujieda Akira, Moji no bunkashi, Kodansha gakujutu bunko, 1999.

Yanaike Makoto, Yokogaki tōjō: Nihongo hyōki no kindai, Iwanami shoten, 2003.

[1] Translator’s note: the full title of the stone tablet is 呉平忠侯蕭景神道石柱題字. An image of the original can be viewed at the Sekino Tadashi takuhon gazō archives hosted by the University of Tokyo.

[2] The translator thanks Zev Handel for his advice in translating into English this inscription.

[3] This and all translations of Tosa Nikki are taken from William N. Porter, The Tosa Diary, Tuttle Publishing, 1981. See pages 59-61 and 80 for the translations cited here and elsewhere.