今野真二

[促音・半濁音をあらわす符号]

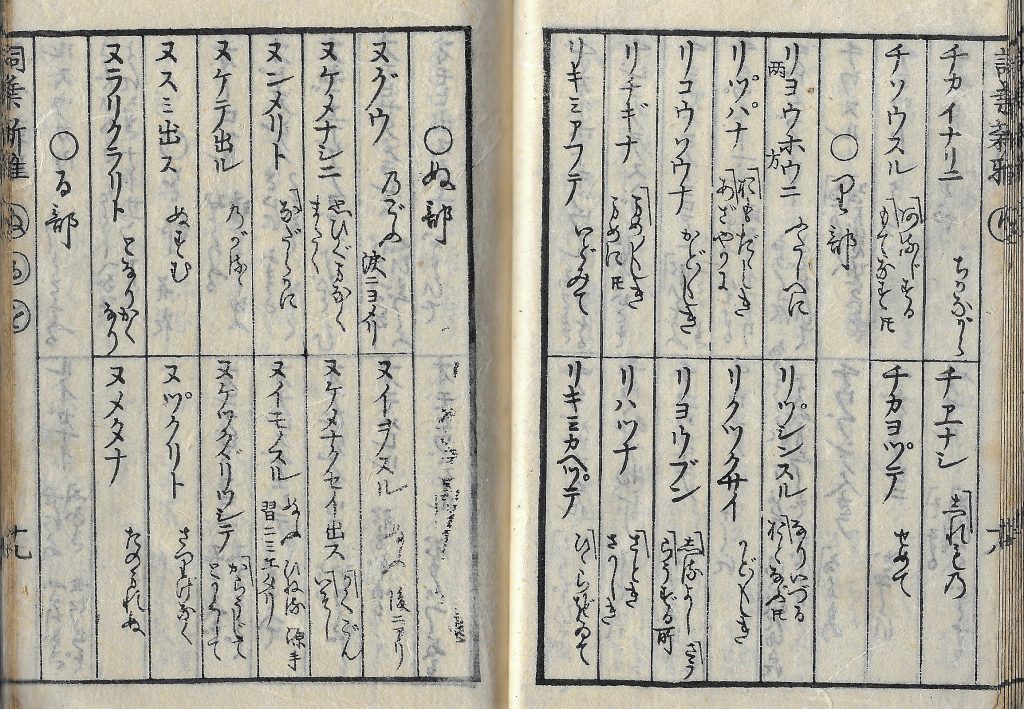

図1(末尾)は寛政4(1792)年に出版された、富士谷御杖『詞葉新雅』の18丁裏19丁表の箇所である。富士谷御杖は、『あゆひ抄』を著わした国学者、富士谷成章の息。

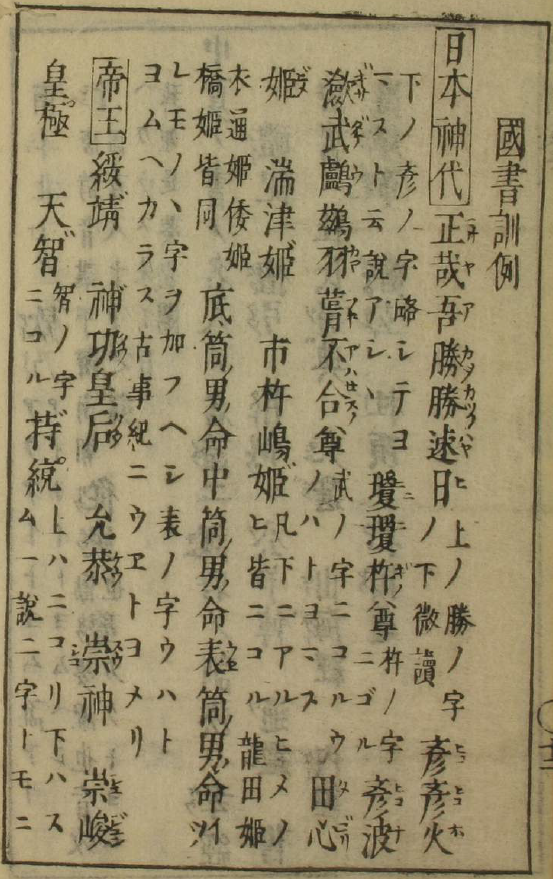

『詞葉新雅』は里言、すなわちこのテキストが出版された時期の「はなしことば」から、古言、すなわち歌作にふさわしい過去のことばを探し出すことができるような体裁のテキストとして編まれている。凡例にあたる「おほむね」においては、「古言里言の別はかんなと片仮名をもてしらす」と記されており、「かんな」すなわち平仮名によって「古言」を、片仮名によって里言を文字化していることを謳う。つまり平仮名と片仮名とを意識的に使い分けていることがわかる。図1でいえば、片仮名で文字化されている「チソウスル」が里言で、平仮名で文字化されている「あるじする」「もてなす」が古言にあたる。「チソウ(馳走)スル」という里言には「あるじする」「もてなす」二つの古言が配されているが、「もてなすともいう」という意味の「トモ」が平仮名でなく片仮名で記されているのは、「トモ」は古言ではないためと思われ、芸が細かい。

「チカヨツテ」「リツシンスル」「リツパナ」「リキミカヘツテ」「ヌツクリト」の「ツ」には右側に圏点(白丸)が附されている。これは片仮名の「ツ」を書いているが、それは「リクツクサイ」や「リハツナ」の「ツ」とは違って、促音をあらわす符号であることを、いわば積極的に示していると思われる。並字で記されている「ツ」には/tsu/をあらわすものと、促音をあらわしているものと2通りあることは、江戸期の日本語使用者には(なんとなくにしても)わかっていたと推測するが、そのことを符号によって明示している。また「リツパナ」において、「パ」には半濁音符が附されている。

半濁音符は、慶長3(1598)年にイエズス会宣教師と日本人信者の協力のもとに長崎で刊行された『落葉集』において使われていることが指摘されている。しかし、江戸期に出版された日本語テキストにおいて半濁音符を使っているものはきわめて稀といってよい。「濁点」「半濁点」という呼称がひろく使われている現在においては、「パ」には半濁点が附されているとしかみえないけれども、「ツ」に附された圏点を、それが促音であることを注意する符号であるとみるならば、「ハ」に/ha/とは発音しない「ハ」であることを注意する符号が附されているとみることはできるだろう。つまり、現代日本語使用者の目に「半濁点」にみえるものが、「半濁点」という概念をもった符号であるとは限らない。

「注意」が発音にかかわるものであることからすれば、富士谷御杖は語の発音に気を配っていたことになる。イエズス会宣教師は日本語を母語としておらず、発音に気を配るのは当然といってよい。

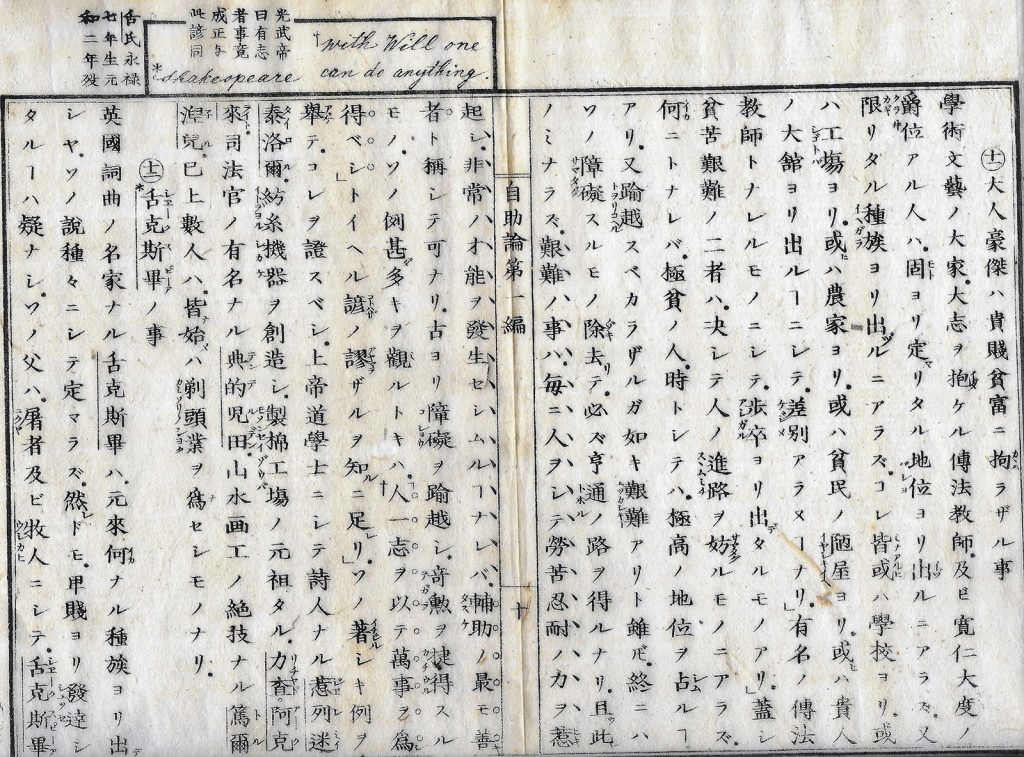

図2(末尾)は中村正直(1832-1891)が、Samuel Smiles(1812 – 1904)の『Self-Help』を翻訳して明治4(1871)年に木版刷り11冊仕立てで出版した『西国立志編』で、第1冊の表紙見返しには「駿河静岡 中村敬太郎譯 木平謙一郎板」と記されている。

第1冊の10丁表10丁裏の箇所にあたる。10丁表の1行目から10丁裏の8行目までが「大人豪傑ハ貴賤貧富ニ拘(カヽハ)ラザル事」で、10丁裏の9行目からが「舌克斯畢(シヱークスピーア)ノ事」である。

『Self-Help』の初版は1859年にジョン・マレー社から出版されているが、中村正直が翻訳に使ったものは1867年に出版された増訂版であることが、例えば『日本語学研究事典』(2007年、明治書院:1095p中段)に指摘されている。

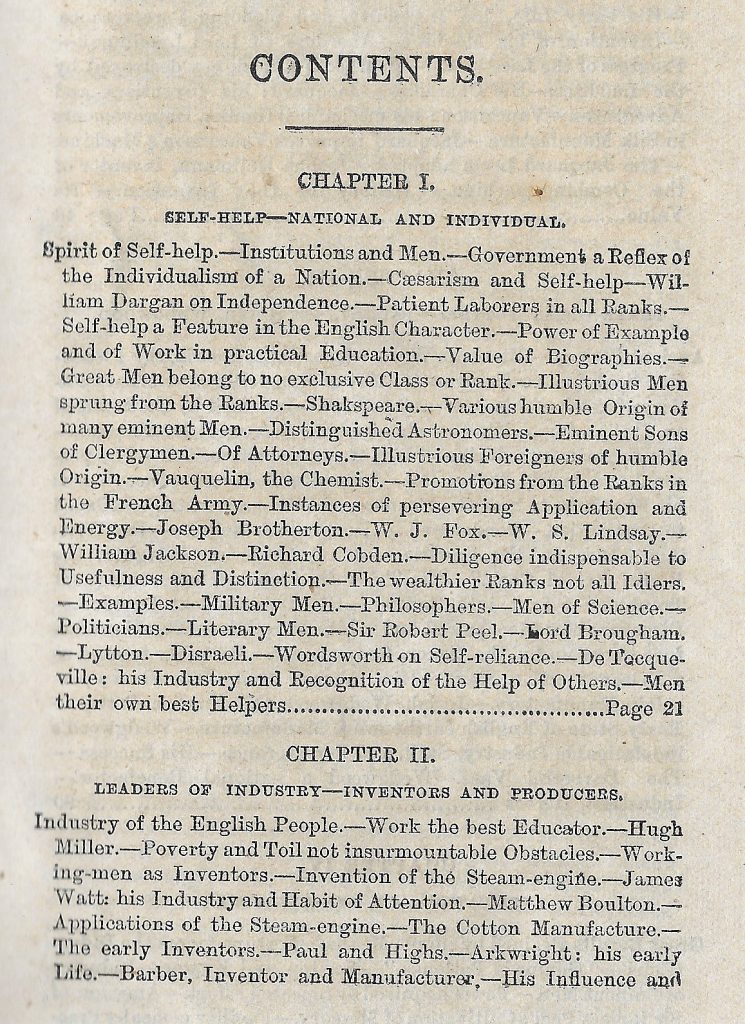

図3(末尾)は稿者が所持している、明治18(1885)年に、東京市日本橋区通3丁目14番地、小柳津要人を発行者とし、丸善株式会社書店を発行所として出版された、英語版『Self-Help』の第4版(明治30:1897年5月4日発行)の「CONTENTS」のページである。翻訳とは、改めていうまでもなく、言語Xを言語Yに「移す」ことで、その移し方にはさまざまなやりかたがあると思われる。そして翻訳はもっともはっきりとした、かつ総合的な言語接触の場面の1つとみることができるだろう。

「CONTENTS」をどう日本語に「移す」かということはひとまず措くが、「CHAPTER」がⅠからXⅢまで設定されている。この「CHAPTER」は木版刷りの『西国立志編』においては、「編」と訳されている。これは、「明治九年十月廿四日 板權免許」という刊記をもち、「木平讓」を「出板人」として、活字印刷されて出版されている『改正西國立志編』、同じ刊記をもち、「木平愛二」「高橋金十郎」「同博親」「青山清吉」「稲田佐兵衛」「福田仙藏」「稲田源吉」の7名を「出板人」とする活字印刷された『改正西國立志編』、明治27年7月10日に発行された活字印刷された『改正西國立志編』(博文館:538p)、大正4(1915)年2月18日に発行された活字印刷された『改正西國立志編』(博文館:512p)、昭和13(1938)年7月10日に発行された活字印刷された『西國立志編』(冨山房:410p)も同様である。つまり、これらのテキストにおいては、「CHAPTER」と「編」とを対応させている。

しかし、山縣悌三郎を「著作兼発行者」とする、明治45(1912)年3月15日に発行された『新譯自助論』(内外出版協会:836p)においては、「CHAPTER」は「章」と対応し、全体を13章に構成している。この1例をもって「この時に」ということはできないけれども、英語「chapter」と日本語「章」とが結びついた「時」があった。これはいわばテキストの枠組みについてのことといってよいが、言語接触の観察は、枠組みと細部とをバランスよく行なう必要があるだろう(註1)。次に「細部」つまりテキストの「具体相」をみてみよう。

[†と*]

10丁裏、すなわち左ページの3行目に「人一志ヲ以テ萬事ヲ爲シ得ベシ」とある。起こしの鉤括弧、受けの鉤括弧ともに使われ、鉤括弧内の13字の右傍には圏点(白丸)が附されている。引用では「爲シ」と翻字して、「為シ得ベシ」は「ナシウベシ」を文字化したものとみた。「シ」は位置、文字の大きさから「送り仮名」と思われる(註2)が、「送り仮名」をどう位置づけるかということも考えておく必要がある。

この小書きされた「シ」を「本行」の文字として数えないと13字ということになる。そして、「人」字の左傍に「†」が附されている。「†」は「dagger(短剣)」をあらわす符号で、ために「短剣符」と呼ばれることもあるが、「*」とともに「参照符号」として使われることがある。ここでは10丁裏の上部欄外に「† with will one can do anything.」と記されており、「諺(コトハザ)」が英語で注記されている。また、十二の「舌克斯畢(シヱークスピーア)ノ事」の漢字列「舌克斯畢」の左側には一本線が引かれ、その始まりの位置に「*」が附されている。そして、上部欄外には「*shakespeare」と英語が示されている。これらの「†」と「*」はまさしく参照符号として使われている。

上部欄外には「光武帝曰有志者事竟成正与此諺同」「舌氏永禄七年生元和二年没」と記されている。前者は、『後漢書』巻19「耿弇(こうえん)列伝」の中で、光武帝(劉秀)が青州十二郡を攻略した耿弇を褒め讃える「常以為落落離合、有志者事竟成也」(常に以為(おも)えらく、落落として合わせがたきも、志有る者は事竟(つい)に成るなり)ということばとしてみえる。このことばと英語の「諺」(with will one can do anything)とのいわんとするところが「同」じであるという注記といえよう。後者は、シェークスピアの生年が永禄七年すなわち西暦1564年で、没年が元和二年すなわち西暦1616年であることを注記している。

英語のテキストである『Self-Help』を日本語に翻訳するということは、英語を日本語の側に「移す」ということであるが、「諺」がどのような英語であるか、「シヱークスピーア」と片仮名で発音を示した「舌克斯畢」が英語でどのように綴られるかを示した、「†」「*」の注記は、いったんは日本語の側に移したテキストを少しだけ英語の側に引き戻す注記といってよいだろう。

「†」「*」によって示されている注記を、そうした英語の側のもの、もともとのテキスト側のものであるみるならば、漢字によって縦書きされている「光武帝曰~」と「舌氏~」の注記は、もともとのテキストの側にあったものではなく、翻訳者である中村正直がいわば持ち込んだ注記であることになる。シェークスピアの生没年を和暦と結びつけることは、まさしく英語圏と日本語圏との対照、「出会い」といってよい。

[鉤括弧]

図2の右側(10丁表)は「大人豪傑ハ貴賤貧富ニ拘(カヽハ)ラザル事」という小題に続いて「本文」が次のように展開する。振仮名を省いて掲げる。

(01) 學術文藝ノ大家.大志ヲ抱ケル傳法教師.及ビ寛仁大度ノ

(02) 爵位アル人ハ.固ヨリ定マリタル地位ヨリ出ルニアラズ.又

(03) 限リタル種族ヨリ出ヅルニアラズ.コレ皆或ハ學校ヨリ.或

(04) ハ工場ヨリ.或ヒハ農家ヨリ.或ハ貧民ノ陋屋ヨリ.或ヒハ貴人

(05) ノ大舘ヨリ出ルコトニシテ.差別アラヌコトナリ.」蓋シ

(06) 貧苦艱難ノ二者ハ.決シテ人ノ進路ヲ妨ルモノニアラズ.

(07) 何ニトナレバ.極貧ノ人.時トシテハ.極高ノ地位ヲ占ルコト

(08) アリ.踰越スベカラザルガ如キ艱難アリト雖ドモ.終ニハ

(09) ソノ障礙スルモノ除去テ.必ズ亨通ノ路ヲ得ルナリ.且ツ此レ

(10) ノミナラズ.艱難ノ事ハ毎ニ人ヲシテ勞苦忍耐ノ力ヲ惹

(11) 起シ.非常ノ才能ヲ発生セシムルコトナレバ.輔助ノ最モ善

(12) 者ト稱シテ可ナリ.古ヨリ障礙を踰越シ.奇勲ヲ捷得スル

(13) モノ.ソノ例甚ダ多キヲ觀ルトキハ.「人一志ヲ以テ萬事ヲ爲シ

(14) 得ベシ」トイヘル諺ノ謬ザルヲ知ルニ足レリ」.

鉤括弧について話題にするが、「始め括弧」「終わり括弧」という呼称を使うことにする。

(05)に終わり括弧が使われているが、この終わり括弧に対応しそうな始め括弧はない。同様に、(14)に終わり括弧が二つ使われているが、最初の終わり括弧は(13)の始め括弧に対応するもので、二つ目の終わり括弧には対応する始め括弧がない。(05)はひとまとまりの言説の終わりを示していると思われる。そうであるならば、現代日本語であれば、段落と呼んでいるようなまとまりの終わりを、終わり括弧で示していることになる。段落の始まりを1字分空白にするのは、終わりではなく始まりを示す形式ということになる。

[傍線]

図2の範囲には左側に傍線がひかれている漢字列がみられる。

(1) 惹列迷泰洛爾 ジヱレミイタイロル

(2) 力査阿克來 リチヤドアークライト

(3) 典的児田 テンデルデン

(4) 篤爾涅兒 トルネル

(5) 舌克斯畢 シヱークスピーア

これらはいずれも外国人の名であり、外国人人名には左側に傍線一本を附していることがわかる。テキストの他の箇所では漢字列「愛蘭(アイルランド)」(第1冊:6丁表10行目)「士班牙未額(スペインヴィゴ)港」(同前:12丁裏6行目)といった外国地名の左側に傍線二本が施されている。

漢籍を「よむ」とは、句読するということであり、その句読を朱で書き入れていくということでもある。亀井孝(1970)は『中華若木詩抄』を具体的に採りあげながら、「古活字の版本にもいろいろあるけれども、その刊行の時期において整版に接続する中華若木詩抄のそれのようなばあい、たとえ時代は書物そのものを貴重としたそういうむかしではあったにしても、いいかえれば、それは、一部ずつ手がきでつくる写本のてまをはぶき、そのかわり、比較的に少部数をすぐさま朱をほどこしてよみうる教材として、‘複写’したものである」(論文集4:252p)と述べている。句読以外にも、国名、地名、人名、書名などの固有名詞を普通名詞と区別するために、字の左右や中央に朱線を引くことがあり、それを「朱引き」と呼ぶ。

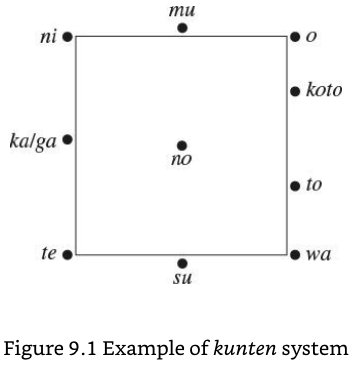

図4は稿者が所持している古活字版『史記』の「孟嘗君列傳第十五」の冒頭。送り仮名、返り点が確認できるが、これらの「訓点」はいずれも墨で書き加えられている。上部、下部の欄外はいずれも書き込み。

また「孟嘗君」「靖郭君田嬰」「威王」「宣王様」などの人名には漢字列の中央に朱線が一本引かれている。その他、区切りをあらわす朱点がうたれている。こうしたことが「朱をほどこしてよ」むということにあたる。享保13(1728)年に出版されている、太宰春台『倭読要領』巻下3丁表には、「此方ノ學者ノ點法ニ.朱ビキトイフコトアリ.地名ニハ./字ノ右ニ單畫(タンクワク)シ.國名ニハ.字ノ右ニ雙畫(サウクワク)シ.人名ニハ.字/ノ中(ナカ)ニ單畫シ.官名ニハ.字ノ左ニ單畫シ.書名ニハ.字ノ/中(ナカ)ニ雙畫シ.年號ニハ.字ノ左ニ雙畫ス.歌ニ曰ク/右所(ミギトコロ).中(ナカ)ハ人ノ名.左官(ヒタリクワン).中二(ナカニ)ハ書ノ名.左ニ(サニ)ハ年號」と記されている。

整理すれば、

右一本:地名 中一本:人名 左一本:官名 中二本:書名 左二本:年号

ということになる。古活字版『史記』は人名に「中一本」線を施している。

ただし、漢字列の中央に一本、または二本の線を引くのは、印刷されている漢字列に手で書き入れるから可能であって、(現在のフロントエンドプロセッサーでは抹消線を入れることができるが)印刷においては入れにくい。明治期に整版によって印刷出版されている『西国立志編』が漢字列の左側も使っているのは、「必然」といってよいだろう。

現代日本語は促音に小書きの「つ・ツ」をあてることをデフォルトにしているように感じられるが、実はそうではない。現代日本語表記は、「かなづかい」に関しては、昭和61(1986)年7月1日に内閣告示された「現代仮名遣い」、漢字に関しては平成22(2010)年11月30日に内閣告示された「常用漢字表」のもとにあるといってよい。

その「現代仮名遣い」の「本文」の第1の4「促音」の条には「はしって(走)かっき(活気)がっこう(学校)せっけん(石鹸)」が例示され、「注意」として「促音に用いる「つ」は、なるべく小書きにする」と記されている。ついでをもっていうならば、第1の2「拗音」の条の「注意」にも「拗音に用いる「や、ゆ、よ」は、なるべく小書きにする」と記されている。

示されている例においては、拗音にあてる「や、ゆ、よ」、促音にあてる「つ」は小書きされているが、「注意」にはなるべくとある。このことからすれば、「現代仮名遣い」においては拗音にあてる「や、ゆ、よ」、促音にあてる「つ」は小書きにしなくてもいいことになる。

「現代仮名遣い」の「前書き」の1には「この仮名遣いは、語を現代語の音韻に従つて書き表すことを原則とし、一方、表記の慣習を尊重して一定の特例を設けるものである」とあり、「従つて」と記されている。このことは案外と知られていないのではないだろうか。

小書きにした「や、ゆ、よ」や「つ」は並字の仮名とは異なるものとみるべきだろう。それはもはや仮名ではなく、使い慣れ、見慣れた仮名を応用した符号とみるのがよいのではないか。それゆえ、小書きの「つ」は/tsu/と発音しない。

昭和61(1986)年以前には、昭和21(1946)年11月16日に内閣告示された「現代かなづかい」があった。この内閣告示以降、これまでの「かなづかい」ではなく「現代かなづかい」(新かな)で印刷され出版されるテキストが徐々に増えていく。そうした「新かな」による印刷をしていると思われるテキストにおいて、促音に並字の「つ」をあてていることが少なくない。

例えば、昭和30(1955)年2月5日に刊行されている「江戸川乱歩全集」第1巻(春陽堂)は冒頭に江戸川乱歩の「自序」を置くが、その末尾において「私の小説は、これまでいろいろな形の本になつて繰返し出版されているが、どの本も校正が厳密でなく、誤植が多いので、この全集は出来るだけそれらの誤植を正すとともに、伏せ字はことごとく埋め、古い用法の漢字を改め、仮名はすべて新仮名遣いに直すことにした」と述べている。この文中において「なつて」とあり、促音が小書きされていない。

「本文」には、例えば、「でも、これ一つが私と、どつか遠い所にいらつしやるお母さまを、結びつけているのかと思うと、どんなことがあつても、手離す気がしないのだけれど、ほかにお贈りするものがないのですから、私の命から二番目に大切なこれを、あなたにお預けしますわ。ね、いいでしよ。」(11p上段)とあり、促音、拗音ともに小書きの文字をあてていない。しかしまたその一方で、「チラッと」「ニヤッと」「スッスッと」(19p)や「チョコレート」(24p)のように、片仮名で文字化した場合には小書きの「ツ」「ヨ」が使われている。こうしたことについては今後考えていくべきであろう。

ここまで述べてきたことを整理すれば、「現代仮名遣い・現代かなづかい」という枠組みの中に、拗音、促音に小書きの「や、ゆ、よ」「つ」をあてる、ということが含まれているという認識は正確ではないことになる。

註1 かめいたかし(1995)は具体的には、いわゆる「古活字版」の技術に関して、「ある民族のその歴史の流れのそのある時点において、突如ある新しい文化がおのれその形をあらわにととのえるに至るこのスペシフィクな、すなわちまさにそれとしての環境にたいし、この歴史のその実態に迫るには、たがいにかかわりあってここに合成力として、もってことのその実現にあずかり資する最適(optimal)の条件を、かつはそれとして誘因、かつはそれとして背景などと、かれこれ、なるべきかぎりは複数の線へ綜合的にアド・ホックに仮設する方がやはりそれだけいっそうさながらなるべしと、そのようにわたくしは考える―。」(188-189p)と述べている。

註2 10丁裏8行目「皆ナ始メハ」の「ナ」「メ」は右寄せで小書きされており、これらは漢文訓読文の「送り仮名」を思わせる。この『西国立志編』は、「漢字片仮名交じり」の「表記体」によって文字化されており、そのことからすれば、テキスト全体は「漢文訓読文の流れ」の中にあるとひとまずはいえるだろう。10丁表3行目には「定マリタル」とある。「マ」は右寄せ小書きされているが、その文字化のしかたと、「マ」を並字にして「定マリタル」と文字化した場合、何が異なるのか。こうしたことについては、ほとんど考察されていないといってよいのではないか。もちろん右寄せで小書きされた「マ」と並字で「本行」に書かれた「マ」とには何も違いがない、という「みかた」もあろう。そしてまた、丁寧に観察、考察したとしても、はっきりとしたことはわからないという可能性もたかい。それでもなお、ひとまずは「違い」として留意しておくという「みかた」は(当然のことながら)あってよいと考える。

参考文献

亀井孝 1970 「中華若木詩抄の寛永版について」(『方言研究年報』13、後に「亀井孝論文集4」:1985年吉川弘文館に再収。引用は後者による)

かめいたかし 1995 『ことばの森』(吉川弘文館)

Chris Lowy

Last time I discussed the three main character sets comprising the Japanese script: Sinographs, hiragana, and katakana. Though orthographic conventions exist, the possibility of orthographic variation allows authors to shape how a reader experiences the text at a level removed from – but still relative to – narrative content. That is, the significance of orthography within a particular text can only be discerned, if it can be discerned at all, through an analysis of script read against content. This time I turn my attention to different elements of the script that work in unison with orthography to establish a larger “style” (buntai) of text: punctuation marks, typographical symbols, and diacritics.

Small Things in English Texts

The smallest things in life often go unnoticed. Those same things can also command our attention if they are misused or were to suddenly disappear. For example, imagine if all the buttons on our clothes vanished into thin air and we could no longer use them. We would still wear clothes, no doubt, but the absence of those little innocuous bits of plastic, metal, wood, or seashells would lead to the emergence of a different style of clothing: button-down shirts would no longer, well, button down, and jeans would need to be reconfigured. Small, yes, but not inconsequential. Written language, too, has its buttons: they are the various markings that complement a text but generally do not have meaning without context. In written English, punctuation marks can signal surprise (!), a question (?), or disbelief (?!); typographical symbols can indicate a footnote (*), abbreviated words (&), or can call attention to a particular participant in a chat (@); diacritics, often limited to loan words or imported phrases, can disambiguate easily mistaken pronunciations (e.g., “it’s saké [ˈsækeɪ], not sake [ˈsɑːki]”), maintain original orthographic integrity (e.g., “I like my cake à la mode”), or even create a sense of foreignness by their mere presence (e.g., “Häagen-Dazs, by the way, is an American company”). They form an important part of the reading experience. While these various markings developed to mimic the rhythm of speech and thus enable oral reproducibility, they became fundamental in establishing written language as a distinct mode of linguistic representation.[1] In contemporary English and Japanese, and indeed in most languages written today, the set and function of these markings is standardized within a character set while significant individual variation exists in their application.[2]

Of course, the form and function of these linguistic buttons is not immutable. Just as clothes existed before buttons and would continue to exist without them, these literary fasteners only recently transformed into the codified sets we know today. At the risk of oversimplification, we can say that both a settled and more sparse use of punctuation is in fact one characteristic of the contemporary period.[3] Consider as an example this passage from Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759-67), an important piece of literature written in decidedly modern English.

Gentle critick! when thou hast weigh’d all this, and consider’d within thyself how much of thy own knowledge, discourse, and conversation has been pestered and disordered, at one time or other, by this, and this only:—What a pudder and racket in COUNCILS about οὐσία and ὑπόστασις, and in the SCHOOLS of the learned about power and about spirit;—about essences, and about quintessences;——about substances, and about space.——What confusion in greater THEATRES from words of little meaning, and as indeterminate a sense; when thou considerest this, thou wilt not wonder at my uncle Toby’s perplexities,—thou wilt drop a tear of pity upon his scarp and his counterscarp;—his glacis and his covered-way;—his ravelin and his half-moon: ’Twas not by ideas,—by heaven! his life was put in jeopardy by words. (Sterne, 62)[4]

While spelling is largely the same as it is in the present day, we see a use of punctuation at odds with current practices. Indeed, the punctuation suggests a printed text reveling in its printy-ness. In other words, Sterne’s use of punctuation marks and typographical symbols reminds the reader they are, in fact, reading. The splash of Greek and, earlier in the book, the famous black screen spread across the concluding pages of Chapter 7 (23-4) foregrounds this self-consciousness. Compare this with the powerful opening passage of Toni Morisson’s Beloved, published in 1987 but set in 1873.

124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom. The women in the house knew it and so did the children. For years each put up with the spite in his own way, but by 1873 Sethe and her daughter Denver were its only victims. The grandmother, Baby Suggs, was dead, and the sons, Howard and Buglar, had run away by the time they were thirteen years old – as soon as merely looking in a mirror shattered it (that was the signal for Buglar); as soon as two tiny hand prints appeared in the cake (that was it for Howard). Neither boy waited to see more; another kettleful of chickpeas smoking in a heap on the floor; soda crackers crumbled and strewn in a line next to the door sill. Nor did they wait for one of the relief periods: the weeks, months even, when nothing was disturbed. No. Each one fled at once – the moment the house committed what was for him the one insult not to be borne or witnessed a second time.

(Morrison, 24)

Compared to Sterne’s text, the use of punctuation in Beloved is restrained, sparse, and cutting. Morrison uses it powerfully, keeping the focus and attention of the reader on the content itself: commas interject names into clauses; parentheses draw nuance to names; colons explain. The power of punctuation is indisputable.

Nevertheless, this potential to steer the reader’s attention to content is not the sole focus of this installment. Rather, I am interested in understanding these markings as the result of various historical processes that include cross-linguistic contact and exposure. This historical reality of punctuation and typographic symbols is true in the case of both English and Japanese. For example, Edward Maunde Thompson, in the monumental An Introduction to Greek and Latin Paleography, notes that a standardized system of Greek punctuation and diacritics can be attributed to Aristophanes of Byzantium (260 BC), a system Latin grammarians largely followed and, at the end of a long and winding road, would lead to the set of markings we use today (Thompson, 60-1).[5] It wasn’t, however, until the spread of printing technologies in the 16th century that these various symbols would begin to stabilize in the Western world (Parkes, 50-61). The story of punctuation, typography, and diacritics in Japanese texts, too, is equally complex.

Small Things in Japanese Texts

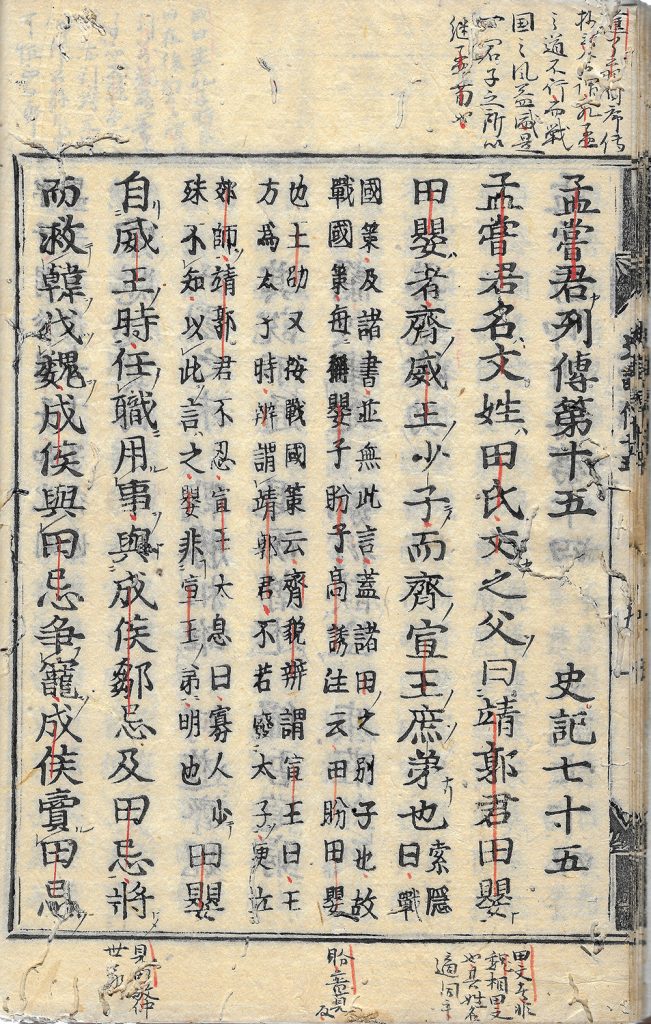

The complete set of punctuation marks, typographical symbols, and diacritics in Japanese is collectively referred to as yakumono (約物). Kutōten (句読点), on the other hand, is more limited in its usage: a combination of kuten “period marks” and tōten “reading marks,” it refers exclusively to punctuation. Punctuation marks (i.e., kutōten) used today in Japanese (、。) originate from Chinese manuscript and, later, Song Dynasty print culture. Reminiscent of the development of punctuation from Greek to Latin to English, the road to standardization in Japanese was a long one. In the Wadoku yōryō 倭読要領 (1728), a text Konno cites in his installment and an important milestone in the development of early modern rules for reading literary Sinitic in Japanese, Dazai Shundai begins his section on punctuation (点書法) by discussing the practice of okoto-ten. Bjarke Frellesvig describes it succinctly as independent systems of “lines, dots, circles, hooks or marks of other shapes which were placed next to or on” Sinographs, and which functioned as “shorthand for grammatical particles or words, auxiliaries or inflectional endings; both the shapes and positions of marks are significant” (Frellesvig, 259).[6] Simply put, grammatical inflections and other matters of grammar could be indicated by placing some marking around the vicinity of a Sinograph (Image 1). There is an important point to be made here: these markings were applied to texts not originally written in Japanese nor written with a Japanese audience in mind. They were, in fact, reading guides developed by Japanese readers for Buddhist sutras and Chinese classics that had already fallen into obscurity by the time Dazai was writing. The shift from passive glossing to active glossing would rise to a crescendo during the flourishing publication culture of the Edo Period, a topic I will return to in a later installment.

After drawing a clear line between punctuation marks (点) and intertextual glosses (旁註), Dazai argues that scholars should follow Chinese rules of punctuation when reading Chinese texts. However, he also notes the unstable nature of these marks.

句読ヲ点ズルコトハ● 其法一様ナラズ● 或ハ圏ヲ用ヒ或ハ批ヲ用フ● 圏トハ● ◯ナリ● 批トハ﹅ナリ● 秘書省ノ校書ノ式ニハ● 句ハ字ノ旁ニ点ジ● 読ハ字ノ中間ニ点ズトイヘリ● There is no standard method for applying punctuation [in Chinese texts]. In some cases the ken is used, and in other cases the hi is used. The ken is ◯, the hi is﹅. It is said that in the editorial style of the Department of the Palace Library [of China], period marks (ku) are placed on the side of characters while reading marks (tō) come between characters.

(Dazai, vol. 3, fol. 2a)

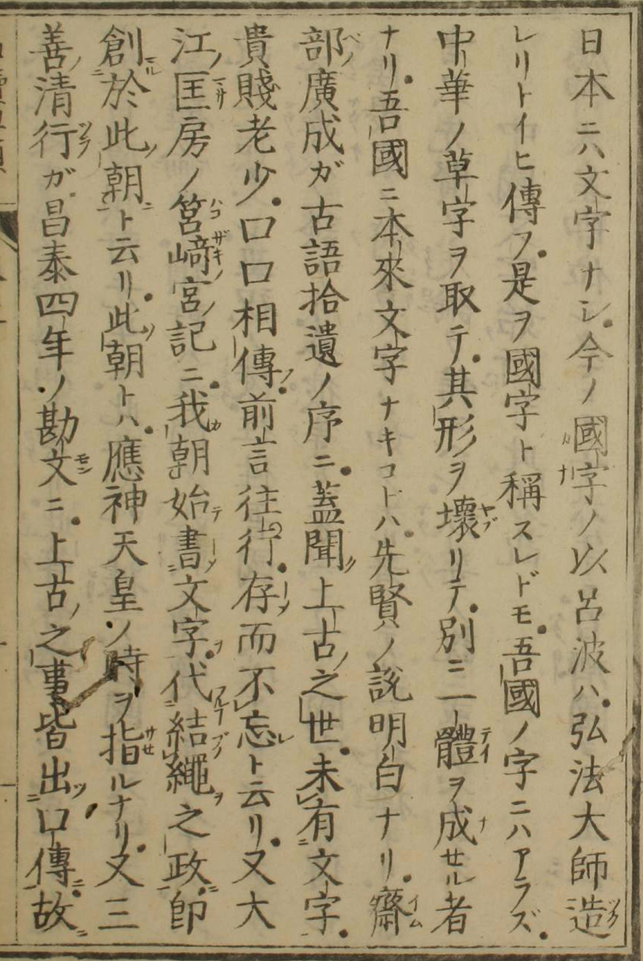

Though the style used by Dazai himself has been influenced by Chinese practices, the main punctuation marks used in Wadoku yōryō are black dots (●) positioned on the lower right quadrant of characters, functioning as both commas and periods, and a single line drawn either in the middle of two Sinographs or to the left of them (Image 2).

The former indicates that these Sinographs should be read in the on’yomi (e.g., 勘文 as kanmon) with the latter indicating the kun’yomi (e.g., 吾國 as wa ga kuni). Nevertheless, through the efforts of Dazai and others, the use of ken and hi would become fundamental components of written Japanese that closely mirror today’s period and comma. As Yanabu Akira notes, however, things were still in flux as late as the beginning of the Meiji Period (1868-1912). It is Yanabu’s claim that only after prolonged exposure to (and engagement with) translations of/from Western languages that a truly standardized set of punctuation marks was established (Yanabu, 26-28).

In fact, exposure to foreign languages shaped every aspect of writing in Japan, including diacritics. In written Japanese today, the dakuten, or voiced sound marker (゛), is added to certain hiragana and katakana to indicate voicing (e.g., て te → で de) while the handakuten, or semi-voiced marker ( ゜), is attached to hiragana and katakana with an initial h- sound to indicate a p- sound (e.g., は ha → ぱ pa). As Numoto Katsuaki has outlined, both voiced and semi-voiced markings did not originate with the authors of a text but, ultimately, with the reader. Voiced markings, for example, began with a desire to indicate (more) accurate pronunciations of dharani (陀羅尼), Buddhist chants and mantras written in Sanskrit.[7] The development of semi-voiced marks, on the other hand, is intimately linked to practices developed by Portuguese Jesuit missionaries to Japan during the 16th century (Frellesvig, 165).

The shape and form of these marks varied depending on who was writing them and when: some texts utilize a character resembling ツ, the first three strokes of the Sinograph meaning “voiced” (濁), while others use an abbreviated mirror image of a character to indicate the same thing (Numoto, 1993). There are also cases of diacritics being attached directly to Sinographs: in Image 3, for example, the ji 持 of Empress Jitō’s name has dakuten attached to it while the tō 統 has handakuten (Image 3). The commentary instructs the reader that 持゛ought to be voiced (i.e., ji and not chi) while 統゜should be unvoiced (i.e., tō and not dō).[8]

Konno cites in his piece yet another use of diacritics. In Fujitani Mitsue’s Kotoba no shinga (詞葉新雅), for example, handakuten are used to indicate a geminate consonant. That is, チカヨツ゜テ would today be written チカヨッテ.

The history and study of (Western) typographic symbols in Japan largely begins with exposure to the Dutch language and the proliferation in the 17-th century of what is called “Dutch Studies” (Rangaku). Though it is a common refrain that in the modern period authors such as Tsubouchi Shōyō, Yamada Bimyō, and Futabatei Shimei modernized the literary form of written Japanese (a process that focused on punctuation marks and typographic symbols), those scholars of Dutch learning systemically discussed Western punctuation relative to the punctuation marks of Chinese texts discussed above (Sugimoto, 269-278). Fumiko Fukuta Earns postures three consequences of this early exposure to Dutch punctuation on Japanese: (i) it “helped to establish the concept of a sentence in Japanese,” (ii) “through the introduction of the quotation marks, the Japanese learned the difference between direct and indirect discourse,” and (iii) desire of some Dutch traders in Japan to standardize spelling influenced Meiji authors to do the same (Earns, 100-101).

There is much more to say on this matter, but I will end my installment here. Small things, it turns out, have much to tell us about the history and development of writing systems.

Works Cited

- Dazai Shundai, Wadoku yōryō, 1728, Waseda University Library Ho 02 04736.

- Earns, Fumiko Fukuta. “Language Adaptation: European Language Influence on Japanese Syntax,” PhD dissertation, University of Hawaii 1993.

- Frellesvig, Bjarke. A History of the Japanese Language, Cambridge University Press 2010.

- Kaibara Ekiken, Tenrei, 1720, Waseda University Library Ho 02 0473.

- Komatsu Hideo. “Fudakuten,” Kokugogaku vol. 80, 1970.

- McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language, Oxford 1992.

- Morrison, Toni. Beloved, Vintage Books 2004.

- Numoto, Katsuaki. “Dakuon jibo kara dokuseiten e.” Kokugogaku 172, 1993, 15-28.

- Parkes, M.B. Pause and Effect: An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West, Routledge 1992.

- Seeley, Christopher. “The Waji shōran-shō of Keichu and Its Position in Historical Kana Usage Studies,” PhD dissertation, University of London 1975.

- Sterne, Laurence. Edited by Howard Anderson. Tristram Shandy: An Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism, Norton Critical Edition, W. W. Norton.

- Sugimoto Tsutomu. Edo no bun’en to bunshōgaku, Waseda University Press 1996.

- Thompson, Edward Maunde. An Introduction to Greek and Latin Paleography, Oxford at the Clarendon Press 1912.

- Wingo, E. Otha. Latin Punctuation in the Classical Age, Mouton 1972.

- Yanabu Akira. Nihongo o dō kaku ka, Hōsei Daigaku 2003.

[1] Robert Allen, in the exhaustive The Oxford Companion to the English Language, defines punctuation thus: “The practice in writing and print of using a set of marks to regulate texts and clarify their meanings, principally by separating or linking words, phrases, and clauses, and by indicating parentheses and asides. Until the 18c, punctuation was closely related to spoken delivery, including pauses to take breath, but in more recent times has been based mainly on grammatical structure,” noting that “[i]n antiquity and the early Middle Ages, points were used, either singly or in combination, to separate sentences, or in some cases (such as Roman inscriptions) to separate words” (McArthur, 824).

[2] There are generally two extremes when speaking of punctuation: “heavy punctuation” and “light punctuation,” the latter being more common in the present day (McArthur, 824). Indeed, the use (or lack thereof) of punctuation is a point of convergence between “style” (buntai) as it is conceived of both in Japanese and English language discourse. Orthographic variation, on the other hand, is more common in Japanese than it is in English.

[3] It is, in fact, the existence of an established set of rules governing punctuation that enable the radicalness of, for example, poems by ee cummings and the avant-garde poets to not only stand out but also engender meaning.

[4] This is the closing passage of Volume 2, Chapter 3.

[5] It should come as no surprise that this is a grave oversimplification. For an overview of (the little) scholarly attention paid to Latin punctuation and the variety of marks used in antiquity, see E. Otha Wingo’s Latin Punctuation in the Classical Age (especially 12-13, 94-130).

[6] Christopher Seeley provides a helpful chart of okoto-ten in Appendix 6 of A History of Writing in Japan.

[7] I am being loose with my use of the term Sanskrit. Shittan 悉曇, a common term for Sanskrit, refers to Siddhaṃ, a medieval Brahmic abugida script used to write sutras in Shingon and Tenda Buddhism in Japan. Mabuchi Kazuo argues the term “was used as a collective term for Sanskrit letters in the context of a systematic table of speech-sounds” while the more common Bonji 梵字 “referred to individual signs” (cited in Seeley, 250).

[8] These marks are sometimes called non-voiced marks (不濁点) and are more generally attached to kana. For more on this see, for example, Komatsu 1970.